Some digital technology, such as remote sensing, satellite imagery and GPS guidance systems, has been around for a while. More cutting-edge digital tools such as artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, drones, digital twinning and wearables are becoming more common on today’s farms.

According to the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute (CAPI), “Digital agricultural tools available to producers today have been proven to boost productivity and competitiveness and reduce environmental impacts with the potential to unlock a further $750 million to $1.5 billion in annual net revenue over the next decade.”

The rate of adoption can depend on any number of factors, for instance, the age of the farm owner, available labour, type of technology, type of operation and infrastructure. It could also depend on the cost to implement, potential return on investment, compatibility with existing technology on the farm and how available are the knowledge and skills needed to utilize the technology and the data it produces.

Read Also

Celebrating women in agriculture

If you’ve been a long-time reader of Country Guide, you’ll have read many articles in our pages over the years…

What’s driving digital technology adoption on farms?

Invariably, the reasons farmers adopt any technology is to improve productivity and efficiency, increase profits and help solve major pain points such as labour shortages. Staying competitive and reducing costs are major drivers.

“Farmers today are competing not just inside their province, or Canada, but internationally,” says Maryna Ivus, manager, economics research at the Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC). “So, competitiveness is an important driver of technology adoption.”

Farmers across the board are struggling to find labour and existing technologies that have helped to address this issue for many producers. The digital era, with advancements in areas such as autonomous farming, remote sensing and sophisticated AI-driven systems to integrate and manage multiple functions and operations, could solve it once and for all.

“Whether it’s true automation technology or just more updated equipment that makes things run a little bit smoother, farmers are investing in what’s needed to allow the farm to operate,” says Phyllis MacCallum, senior program manager, research and knowledge mobilization, Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council (CAHRC). “It can allow a production facility to continue on if they are short-staffed. And herd health is important whether you are in milk or beef production, so these technologies can allow farmers to monitor and ensure that the herd is staying healthy while they manage everything else.”

Setting the stage for autonomous agriculture

AI, machine learning and autonomous technology are at the forefront of technological trends in agriculture and many other industries. In agri-food, AI is being used for diverse applications from managing greenhouse operations to evaluating embryo viability in cattle.

“Automation and AI allow for 24/7 operations, which means constant quality control as well as safety control when it comes to worker performance, as well as reducing costs through things like precise use of fertilizers, water and other inputs,” says Ivus.

“AI-driven planning tools for co-ordinating field equipment are starting to gain traction, especially in Western Canada where large grain and oilseed farms rely on multiple machines working together,” says Godard, CEO and co-founder of Verge Ag, a company that creates AI-driven software designed to help farmers plan, simulate and streamline how their equipment operates in the field. The aim is to make existing equipment more efficient, ease the workload on operators by optimizing routes, and reduce costs by minimizing overlap and reducing fuel consumption.

“Since most farm equipment already comes equipped with GPS and autosteer, these optimized routes leverage existing capabilities, bringing us closer to a future of fully autonomous farming,” says Godard.

The tech can work for any type or size of farm, although larger farms tend to see the most immediate impact because even small efficiency improvements can lead to significant cost savings. However, benefits such as reduced overlap, lower fuel consumption and improved timing apply across the board.

Digital twin technology

Digital twin technology, while well established in the gaming industry, is a relatively new concept for agriculture. On its website, IBM describes a digital twin as “a virtual representation of a physical object or system that uses real-time data to accurately reflect its real-world counterpart’s behaviour, performance and conditions.”

“If you are looking to invest, to innovate and create better efficiencies on the farm, this technology has the ability to do that,” MacCallum says.

Whether you are bringing innovation in, or you are remodelling, you can use digital twinning technology to simulate what it would look like once everything is put in place, and assess whether that would create efficiencies and, overall, more profitability. It allows you to physically see how things will look in a 3D form before you execute.

Phyllis MacCallum

Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council (CAHRC)

“For most of the people taking this program, digital twinning is a new technology, and they are learning about its capabilities. There is so much capability for the technology, no matter the farm or the application. There is always a way to incorporate this. The technology can be as simplistic or as complex as someone wants it to be.”

But digital twins are not just for planning; they also form the basis of a fully functional system connected to sensors, robots, cameras and other technology that can allow for continued remote monitoring and managing of operations. It could also be used to create virtual reality models for things such as health and safety training.

CAHRC is working with various partners and Palette Skills to offer a free 12-week training program called Seeding Digital Skills that introduces farmers and employees in agriculture and the food and beverage processing industries to digital twin technology. The program, valued at $12,000, is currently being funded by Upskills Canada.

“There is so much opportunity to co-ordinate with other applications like sensors, so it is monitoring the field and growth,” MacCallum says. “Or for sustainability questions in terms of crop production, to determine where the most efficient use of the land is, (for example) if you have marginal land, whether that needs to be left because it’s not returning an ROI or be put into a different level of production.”

Using AI to manage risk

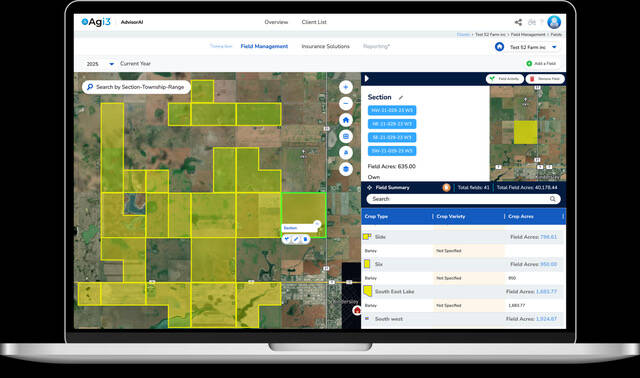

A real-world example of digital twinning is offered by Agi3. The platform brings crop planning and risk management tools into one AI workflow. Farmers can create a field-level digital twin that connects with land, climate, management and market data to generate a risk profile and individualized insurance options.

“Farmers gain fair, individualized coverage and pricing that reflect their actual fields and practices, not provincial averages, so strong management is recognized rather than averaged away,” says David Hodge, chief strategy officer for Agi3 Group.

“With risk and coverage properly aligned, farms can invest in productivity-enhancing practices with greater confidence, instead of ‘farming to the average’ and leaving margin on the table.

“Claims are faster and more defensible because losses are verified with time-stamped, geo-referenced evidence, which improves program integrity and reduces friction. Agi3’s platform also provides a clean digital twin of the operation, simplifying planning and interactions with lenders, insurers and other partners. Overall, these elements deliver better protection, stronger economics and clearer, data-driven decisions for farmers.”

What is holding some farmers back from adopting digital technology?

CAPI’s report The Future is Digital: Digital Agriculture and Canadian Agriculture Policy, notes that adoption rates of digital technologies among Canadian farmers remain low due to factors such as poor rural connectivity, costs and uncertainty about the return on investment (ROI) and concerns over stewardship of the data that these technologies generate.

“If farmers are financing a technology, that is a risk, and that technology often requires additional finance for things like energy or additional infrastructure, for example broadband access. Securing an autonomous tractor doesn’t mean that you can utilize it tomorrow. There are additional expenses that sometimes are not clear. So, financial concerns are definitely number one for most farmers.”

Maryna Ivus

Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC)

It’s often difficult to calculate the ROI of digital technology because it can take several years before benefits, such as productivity or profitability, start to show. Furthermore, some of the benefits can be intangible, such as improved safety.

“It has to be able to pencil out, whether that is over a number of years or over per head of cattle,” says MacCallum. “For producers who may only have a few more years in the industry, or those just entering the industry, they have to ensure that the investment that they’re making is worth the time and the commitment, and that in trying to find the efficiency, it doesn’t slow them down in profitability and production by investing too big or too fast. There is a lot to consider.”

Another big hurdle to adoption for many farm owners or managers is having the skills and knowledge to actually use these technologies and understand the data that they generate.

“It’s not about just acquiring the technology, it’s having someone who can use it and understand and analyze the data properly to make sure that it’s not underutilized,” says Ivus. “Someone who has the background in technology and agriculture is hard to find.”

Compatibility with other technologies already being used on the farm and ensuring that they can both connect and communicate with each other, can be another challenge. It may require some specialized skills to overcome but may also require farmers to think differently about how they approach getting the work done on their operations.

“The main hurdles are more about behaviour than technology,” says Godard. “Most farms already have the necessary hardware, for example, GPS, autosteer and precision guidance, but aren’t yet using planning software to co-ordinate machine operations across their fields. This requires a shift in how farmers approach their work, with more emphasis on planning digitally before heading into the field.”

There’s gold in the data

Digital technologies continuously create a monumental amount of data. Every operation in the field or cycle of production generates information that has tremendous value to help improve operations, offer solutions to create more efficiencies, identify and address problems, and create more profitability on the farm, but it’s not much use unless it has been properly analyzed and made useful. AI is going to play a big part in unlocking the ‘gold’ in that data.

“As producers innovate at a pace that’s comfortable for them, how do we ensure that they can harness the data that they are collecting?” MacCallum asks. “How do we ensure that data is available to them and that they can use it to better their production system? A producer who is busy running his operation doesn’t have time to sit down and look through thousands of data points, so how do we set up AI to analyze and generate reports or summaries that show the trends through this data collection so producers can better use that information?”

Who owns the data?

Farmers are understandably concerned about who actually owns the data that is being generated by all the technologies on their farms, where that data ends up and what is being done with it.

“It comes down to an issue of trust,” says Dr. Emily Duncan, department of sociology and social studies, University of Regina. She carried out a large-scale survey of 1,000 farmers across Canada around the adoption of digital technology, which was summarized in the report I grow food, IT people do cybersecurity: Addressing cybersecurity risks in Canada’s agri-food sector.

“Farmers had a lot of concerns around where the data goes once it leaves their farm, because end user license agreements, or the terms and conditions of using these platforms are not very clear about what that company can do with the data,” she says. “That does hold farmers back because the decisions that you make on your farm, how you get to that level of productivity, or what you use, is information that you might not want shared widely with third parties.”

Although farmers acknowledge that there is value to data sharing, Duncan learned that they are more comfortable sharing certain types of data than others.

“Farmers were more comfortable sharing environmental information like weather data that they might collect from an on-farm weather station, or soil data that they might collect from soil testing or soil mapping,” Duncan says. “When it came to data about decisions around use of inputs and productivity levels, these were types of data that farmers were much less comfortable sharing.”

It also matters to farmers how their data is shared. Farmers were most uncomfortable sharing raw data that comes off the sensors or implements on their farms. Once that data is uploaded to their service provider’s platform and is combined and averaged (called summarized data), they were a little more comfortable sharing it. The data they were most comfortable sharing was fully aggregated data that is pulled from many different farms in the region and remains anonymous.

Finally, Duncan asked who farmers are most comfortable sharing data with.

“Farmers were generally more comfortable sharing with industry groups, other farmers and researchers, and rated tech service providers as the actors they were least comfortable sharing data with,” Duncan says. “These are the people who have access to the data and are the people that farmers have little trust in.”

Dr. Emily Duncan

Department of sociology and social studies University of Regina

That could be because farmers are also skeptical about who is benefiting most from the data that they are subscribing to and paying for.

“Farmers aren’t really seeing any of the returns from the data that they are generating that these companies are making profits off,” Duncan says.

Despite all the misgivings that farmers may have about digital technologies, Duncan believes the industry is heading in the right direction.

“Farmers are interested in technology and are keen to improve their productivity and sustainability through new tools,” she says. “The challenge with new tools is sometimes they create a whole new set of problems, like issues around cybersecurity or trust and data sharing governance, but I think the industry is moving in the right direction in terms of trying to develop sector-specific solutions that empower farmers, and that is the most important thing.”