Growing up, I always admired the work that Dad did on the farm,” says Dane Froese, 30 years old and eight years into his plan to become a fourth-generation farmer at Winkler, an hour and a half south of Winnipeg.

Froese doesn’t round off the edges. He knows what he wants, And he knows it isn’t what everyone thinks he should want. So even though so much of what he sees in the business-driven world of modern farming is all about growth, a ton of his focus is on quality of life.

“To me, farming is not just about making money off it,” Froese says. “Although it is a livelihood, it’s the lifestyle too.”

Read Also

When hackers hit the barn

As Canadian farmers embrace automation, cybersecurity is the new front line. Here’s how to protect your on-farm data from digital threats.

It’s an idea that’s driven him from the start. It may seem like a stereotype to say farmers are an independent lot, but to Froese it’s much more than that. It’s the whole point. He’s determined to be responsible for his own success.

“I knew I wanted to grow to a point where I could manage the farm by myself, or maybe with a hired hand or some family help,” he says. “I don’t want to grow to the point where I’m a ‘factory farm’ where it’s a huge, massive corporation and I need 15 employees to manage it.”

He’s got a maximum number of 4,000 acres in his head. Any bigger, he says, and he’ll lose what he values most. He’ll lose the feel of his fields, he’ll have to give up farming as a way of life, and he says the farm will end up “an income line on a spreadsheet.”

To some, that might seem unambitious. It might even seem like Froese must not have what it takes to run a sophisticated modern farm, especially in a business context.

Instead, as Froese already knows, finding a middle way is going to take some serious business smarts. Very serious indeed.

From the start

For the past eight years, Froese has been working in collaboration with his dad, who still operates the 2,000-acre grain farm he started in 1991 and who is only now beginning to look at retirement.

In other words, Froese, like a lot of other farm kids, grew up on a farm that has limited ability to support a second family without expanding and putting significant financial pressure on his parents, Garry and Barbara.

“When I started, my parents’ farm operation wasn’t as big as it is today,” Froese says. “And I knew that any acre I rented or took away from my parents limited their ability to expand or pay things off and have a comfortable retirement, so I never wanted to look at renting out their land right away — I knew I had to go find my own.”

It forced a rethink. Froese had never entertained the idea of an off-farm career, but when he graduated from the University of Manitoba, he went to work as an agronomist. Today, he is Manitoba Agriculture’s provincial oilseed specialist.

“That was something to adjust to … having an organizational structure and someone telling you what to do sometimes,” Froese admits. “While I love my professional career, and it’s opened a lot of doors and exposed me to new things and new ideas to try on the farm, it makes me appreciate and want to be a full-time farmer.”

That desire proved the impetus for Froese and his wife, Dominique, to grow their farm operation, which started out as 192 acres rented from neighbours eight years ago, to just shy of 800 acres today. The dream of farming full-time is almost within his reach.

“My plan was to grow my own farming operation to make it self-sustaining and reach that economy of scale where I can leave the off-farm work,” he says.

“I’ve always kept a separate set of books from my dad’s operation because I didn’t want to rely on the family farm to subsidize what I wanted,” Froese says. Again, he knew what he wanted: “to prove to myself that I was successful and able to do it on my own.”

Together, sort of

“The goal we all have is for my farm to succeed and take over the family farming operation as my parents start to wind down,” Froese says.

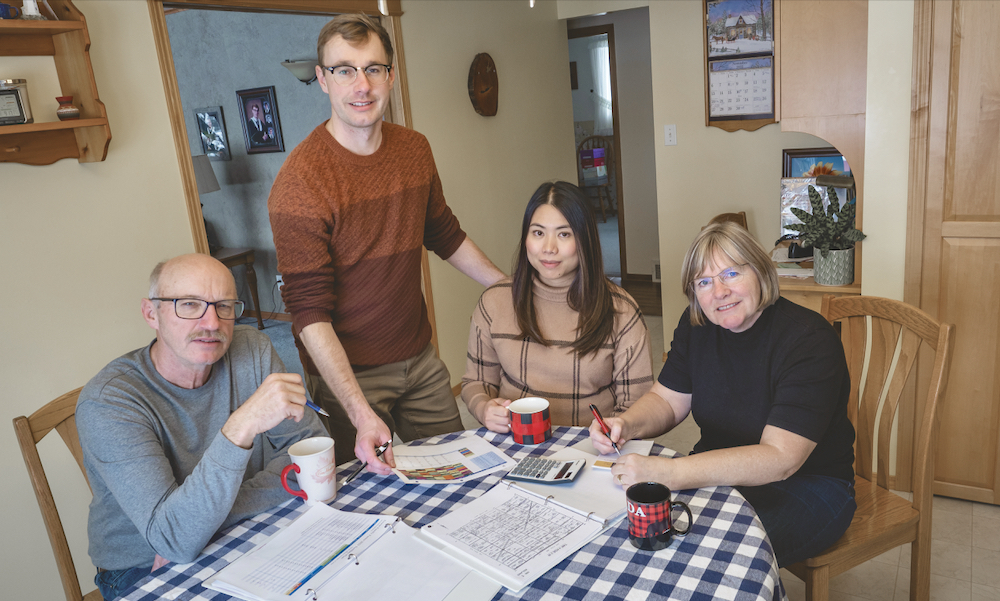

Getting there, though, is taking a lot of the independence that he puts such a value on. Froese and his dad Garry farm separately but collaboratively, with Froese trading his agronomy and crop science and his grain marketing skills for the use of his dad’s machinery.

“We trade time and labour for use of machinery,” Froese says. “Other than having some shared repair and equipment upgrades, we live financially independently and just happen to work out of the same farmyard.”

That said, Froese acknowledges that without his parents being willing to sign on as guarantors for some of his loans in the early days, it would have been much harder to get started.

“Thankfully, they were in an established enough position that they were able to do that,” he says, but his independent streak still finds it a tough condition to reconcile at times. “It’s been an annoyance for me because every time I want to do something, even eight years into it, I still don’t have the equity to make the larger, bigger steps forward into the farm career. It’s a condition we are working on because I also don’t want them to have a piece of land or equipment tied up as collateral that they could leverage against something else should they wish.”

Froese, as with many next-generation farmers, has benefited from the good reputation that his parents have built with lenders over the years, but he has also learned to be respectfully confident in his dealings with lenders and to be well prepared to have financial and business planning conversations with them.

“I view (my relationships with lenders) as a business partnership,” he says.“They are certainly providing me with a benefit, but I am providing them with a benefit too. That makes me think that we are on an equal footing … I am not flustered by questions that come out of the blue. I think through different scenarios ahead of time; the what ifs. I don’t want to be wasting time with indecision. I like to have those situations thought out and prepared.”

It’s an orderly transition model that, so far, is proving successful, with Froese starting to rent some of his dad’s acres. He knows how fortunate he is to have a transition plan that is already well underway.

“Many younger farmers wait to take over the family farming operation … We have got a different approach. I would like to do it sooner than later, not to push family out but to let them take advantage of their lifetime of hard work, and be able to do what I want to do and make the changes necessary for future success.”

The relationship that Froese and his parents have is crucial to the transition process. They talk often and look to identify decisions they can make jointly that benefit both their operations. A good example is some recent conversations about how they can improve their grain handling infrastructure to help solve a constant issue with labour.

“We know that because we’re always short of labour, when we’re able to harvest and get a crop off quickly, if we have the machinery and infrastructure to do it, we can keep the trucks rolling, the cart unloaded rapidly enough that we can take advantage of the labour help when we have it,” he says. “We are all looking at it to try and figure out how do we do this, do we need a new farm yard, do we need a new farm space to do it, and who makes that investment?”

It’s taking longer …

Froese has good budgeting and financial planning skills and he projected at the outset that he would need to grow to around 1,000 acres to fully support himself from the farm operation.

His goal was to be proactive and collaborative and try to make himself ready for any opportunities to expand that came within reach. In the early years, though, he was disappointed those opportunities didn’t come as easily or as frequently as he had hoped.

“I would look for rented land and not be able to rent it because it went for a slightly higher price than I could afford, or a piece of land was sold a couple miles away just outside my budget to a larger farmer or a farm that was well established,” Froese says. “Some of those farmers were approaching retirement age already, and just seeing the big ones get bigger and not seeing room for the small ones to grow and take over was hard.”

It reminded Froese how lucky he was to come from a farming family where he did have shoes to grow into when his dad decided to step back and let go of his own land, but in the meanwhile he remained frustrated that he couldn’t grow quite as fast as he wanted to. But he didn’t give up. If anything, the experience has made him more creative.

The early letdowns made way for later opportunities and a chance to fine-tune his strategy to make sure he was more able to capitalize on them. He was able to buy another quarter section last Easter, he points out. “At that point I had built good relationships with my lenders and made sure that they know what my growth plans are.”

He’s also pursuing alternative financing sources and is currently looking at partnering with Area One Farms, a company that invests in farmland with local farmers. The farmer farms the land and eventually buys the company out over a period of time.

“That’s a new partnership that I’m working on with that company to make our first purchase this coming year. It’s another way to look at expanding.”

As Froese became more established and built a reputation for himself as both a successful farmer and trustworthy agronomist, more opportunities began to come his way to rent or purchase some land.

“I’m a serious farmer. I’m not just doing this as a part-time hobby, and I am looking to grow. Maintaining those good relationships with neighbours and folks in the community goes a long way.”

Where are the young farmers?

2021 was definitely the toughest year in Froese’s farm career. Because of the extended drought he was in a major crop insurance claim position for the first time.

“That financial stress was rough and I thought for sure that was going to delay my full-time farming by several years just to recover from that, but we’ve been fortunate with good weather this year, and despite the late seeding, things came off relatively well with good yields and good markets all happening at the same time,” he says.

As well, it’s helped reinforce how important it is that he stay on top of his numbers.

“It emphasizes to me that I need to know my numbers well and actively seek out those resources and training opportunities that are out there for young farmers and connect with other farmers,” he says.

Yet connecting with other farmers of Froese’s age and using them as a sounding board for working on the kinds of solutions beginning farmers need is something that has proven difficult because there are so few such farmers in his area.

“If I look in my immediate back yard, I don’t know of a single farmer under 40 within 10 miles in any direction,” he says. “Many farmers are a generation older than I am, and so they are often looking at farming more from a retirement perspective versus actively being in growth mode and looking at ways to increase or diversify.”

[RELATED] A young farmer’s fresh start

But there are an increasing number of very large farm operations in the area, and this may prove important, Froese feels. “I hope it gives me some opportunities with other neighbours who maybe would like to see their farm go to another generation,” Froese says. “I hope that when they get to that point that they are thinking of retiring, they might think about a younger guy coming in, and not just sell the farm for the profit, but to value someone else who is farming with sustainable farm practices in order to build the future for the next generation.”

Learning to value everyone’s strengths

Still, Froese is frustrated that he isn’t able to be on the farm as often as he would like to make the day-to-day decisions. Instead, he relies on his dad, an uncle who helps out on a casual basis, and an employee who is fulltime through the spring, summer and fall to do most of the field work.

“The back and forth across the field will be done frequently by someone else but I also have the luxury of taking some vacation time throughout the spring and fall, so I do a fair bit of it, but it does mean that I may miss some details, for example problems with machinery,” Froese says.

But, in the process he has learned that everyone has their niche and it’s important to recognize and make use of people’s strengths and talents. Froese takes on the roles he is good at: much of the grain marketing, crop planning, fertility work and crop scouting, while his dad (who is also a trained mechanic) still does a lot of the field operations (when Froese isn’t able due to his off-farm career), as well as equipment repair and maintenance.

That also applies to Froese’s wife, Dominique, who was raised in Winnipeg, and although she also has a parallel career as an engineer, working in the nearby city of Winkler, she enjoys the farm experience, and helps out where she can. She has learned to drive some of the farm machinery, and has embraced the farm life so well the couple have decided they will actually live on the farm next year, cementing Froese’s commitment to farm full-time as soon as he can.

“She’s been an excellent support and has thrown herself into it to the point now where we’re building a house on a secondary farmyard and looking to move to the farm next year,” Froese says. “We’ll have a physical presence being that much closer instead of 20 minutes away in Morden, where we currently live, which will make us more in tune with the day-to-day decisions and knowing what needs to get done when it needs to get it done.”

Froese has also started to do some custom agronomy for other farmers as a side venture, and it’s worked out well not just from a business standpoint, but also in terms of growing his reputation as an established farmer who knows what he is doing.

What the future holds

Froese is almost nine years into his farming career now, and with family plans, the idea of building a legacy is even stronger.

The immediate plan is to continue expanding the farm but not necessarily by buying more acres, rather by stabilizing the land he already has and then making it as productive as he can.

“The growth pattern is to make sure we have either long-term or purchase land that we already farm to make sure land base is stable,” he says. “We are not necessarily growing the farm for growth itself but farming each acre more intensively and managing carefully what we do.”

[RELATED] Planning to grow your farm?

Although Froese has a good handle on a lot of the business planning, and monitors his financials closely, he knows he will be seeking further training for some of the higher-level decisions that are on the horizon with a full-time operation, especially one that is also transitioning into ownership and management of his parents’ farm.

“My system is spreadsheets, and it works for me but I’m not able to do some of the more fine-tuned things and look at specific financial ratios, it’s a little bit beyond my grasp,” he says. “I want to get better at that, and I have an accountant that is a good help but I need to understand why he does what he does. I always ask why; I have done that my whole life. I need to understand the mechanism and then I’ll trust someone else to do it on my behalf, but I don’t like trusting blindly.”

Incorporation may be on the books for the future, although Froese hasn’t taken that step yet, but he recognizes that the farm management will only get more complex, but also more exciting.

“The next big push we would like to make is move more fully into precision ag and automation on some things such as remote sensing and variable rate technology,” Froese says. “As the technology has improved and gotten cheaper, we should be able to move in that direction.”

Over the next 20 years, he wants to see the farm become more diversified than the one he and his dad run today. He knows that will be partly driven, too, by a changing agricultural landscape different than the one farmers are used to today.

“I see regulation and environmental law moving to a point where it’s going to be hard for us to buy and apply fertilizer the way we have,” he says. “We already are following the 4R practices as best we can and making the most efficiency out of it, and I’m not sure how much more efficient I can get. I don’t know if the research and technology is here to do that sort of thing, but we might see a return to having organic sources of fertilizer, livestock waste and manure, that sort of thing, from the local environment.”

The Froese farm used to raise cattle and pigs and although Froese doesn’t see a return to that kind of mixed farming model, he is interested in working with neighbouring farmers who have beef cattle to do some rotational grazing, and has been taking courses to learn more about these practices.

“We could intensively mob graze and have the cattle re-fertilize a patch of ground, or we could fence some of our current land and having them stubble graze at the end of the year to take advantage of any spilled grain and return some fertilizer the soil,” he says.

He’s keen to try other, newer crops besides the basic wheat, oats, canola, soybeans and corn and is experimenting with different cropping practices such as intercropping and cover crops to help with issues like drought, excess moisture and soil health. He is ready for a step change in production management and to meet the demands of a changing marketplace based on consumers’ preferences.

“I want to take it to the next level, where everything is being recorded, and tracked,” he says. “I may be able to hit some of the market-imposed requests for an identity Preserved product or a production practice that could be fully traceable through the marketplace. We’re seeing some of those incentives already, not super-high but they are enough to make a difference, and I can see that happening more frequently. I want to be prepared to make decisions as the market requests things instead of being dragged kicking and screaming into the future with changes that are being made for me.”

Froese is also convinced the trend to growing more food closer to home is not going away anytime soon and he sees ways that farm operations like his can diversify to take advantage of that.

“Bringing food a little closer to home, and being able to show where that food comes from and that I am implementing things to hit sustainability requirements will mean being able to maintain that social license to farm because we’re not all little red barns and overalls anymore,” he says.

Other innovations may take him even further afield. Froese is looking into greenhouse growing on a larger scale, again to serve a growing demand for year-round, local produce. He has been involved from a plant quality perspective in the small greenhouse business, selling flower and vegetable plants, that his mom and aunt (a schoolteacher and nurse, respectively) started after they retired.

“Greenhouse production has always been an interest of mine, and I think there’s huge opportunity to expand that,” he says. “There is room to produce year-round once the farming season is done; winter production could take over to grow greenhouse tomatoes and that sort of thing. I think it’s a way to diversify and extend the season, especially if I were to use a biofuel source.”

Building a future

Dane Froese’s parallel careers on and off the farm have been synergistic and have built off each other.

“I’m better at my current job as an oilseed specialist because I get to practice what I preach and try things out on my farm,” he says. “I understand the hardships and realities that the average farmer is going through if they call me with a concern or a question; or what needs the industry might face because I am in the industry too. It’s not just a job that I clock out of and go home at the end of the day; I live and breath it too and that makes my day job better so they both work well hand-in-hand.”

It’s the reason that Froese is a big advocate of young farmers developing a second set of skills besides farming.

“I would love to see more young people develop another set of skills,” he says. The advantage he sees is that those unique skill sets then provide more opportunities for the farm. They may provide openings for diversification, or to adopt new technologies, even autonomous field operations.

Froese also know the value of travelling and seeing the world beyond the farm. He spent some time in Brazil and said it was a great learning opportunity not only about farming techniques and systems, but also the importance of farming in wider society; the bigger-issue picture that often isn’t taught in university, and that people with too narrow a world view don’t get to see or consider.

Counterintuitive as it may be to Froese’s go-getter character, he’s beginning to learn a lot about patience.

“I am learning that it’s no use banging your head against the wall because you don’t see things going as fast as you would like,” he says. “The average farmer only has 40 crops or so in their career to learn about, adopt and implement a practice on the farm. New ideas have to be thought through carefully, and so I would rather take that leap sooner than later. Forty crops may be all I get, but I am looking forward to them all with optimism.”