Some farm managers love to spend the winter poring over their financial statements and analyzing all ratios and indicators and how they’ve changed over time.

Others would rather be outside working with cattle or at conferences learning the latest disease management techniques.

If you’re not in the first category, your banker might know more about your farm financial indicators than you do.

Read Also

Where convention and innovation meet

How one Ontario farm is integrating technology into their beef operation.

There are such long lists of financial indicators available it can be hard to know where to start. And once you calculate a financial ratio, how do you know if yours is “good”?

If you don’t calculate these three financial ratios, your banker will. So, why not start by doing the math at home and taking them along to your next meeting?

Why financial indicators matter

Rising land prices have pulled up many farmers’ net worth statements.

“There is not an equity issue out in farm country. Most operators are holding land that has appreciated well,” says Craig Macfie, founder of consulting firm Spring CFO (link to www.springcfo.com). Macfie has seen all kinds of farm financial statements through his consulting work, as an accountant, as a past CFO for Monette Farms and through his experience as a farmer in Crystal Springs, Sask.

But lenders care about more than net worth. Lenders want to know if your assets are generating profits, and if you’re able to repay loans.

In some banks, Macfie says, “the bank credit department is God, and your bank relationship manager is the Pope.” That is, the banker you meet with doesn’t typically have authority to make lending decisions without support from someone in the credit department.

When you need a loan, Macfie says, “You need the Pope on your side, advocating for you.” Your bank manager can tell the credit department what a strategic farmer you are, but the credit department is still going to want to see the numbers.

Your financial indicators will have to carry the day.

The lenders’ perspective

Macfie suggests three key financial indicators can show your farm’s ability to repay loans.

Roxane Lieverse is an executive vice president and the head of agricultural banking with Rabobank in Canada. When asked which financial indicators are important for lenders, she lists the same three indicators.

The financial indicators these two professionals see as highly relevant to bankers are:

- Working capital to expense ratio

- Debt service coverage ratio

- Debt to equity ratio

Together, these three indicators show lenders your farm’s recent financial performance and your farm’s ability to repay loans.

1. Working capital to expense ratio

What it measures: The working capital to expense ratio measures your farm’s ability to stay in business through the next production season.

“It shows the actual working capital available for a producer to put in their crop, whatever it is they’re growing or producing,” Lieverse says.

How to calculate it:

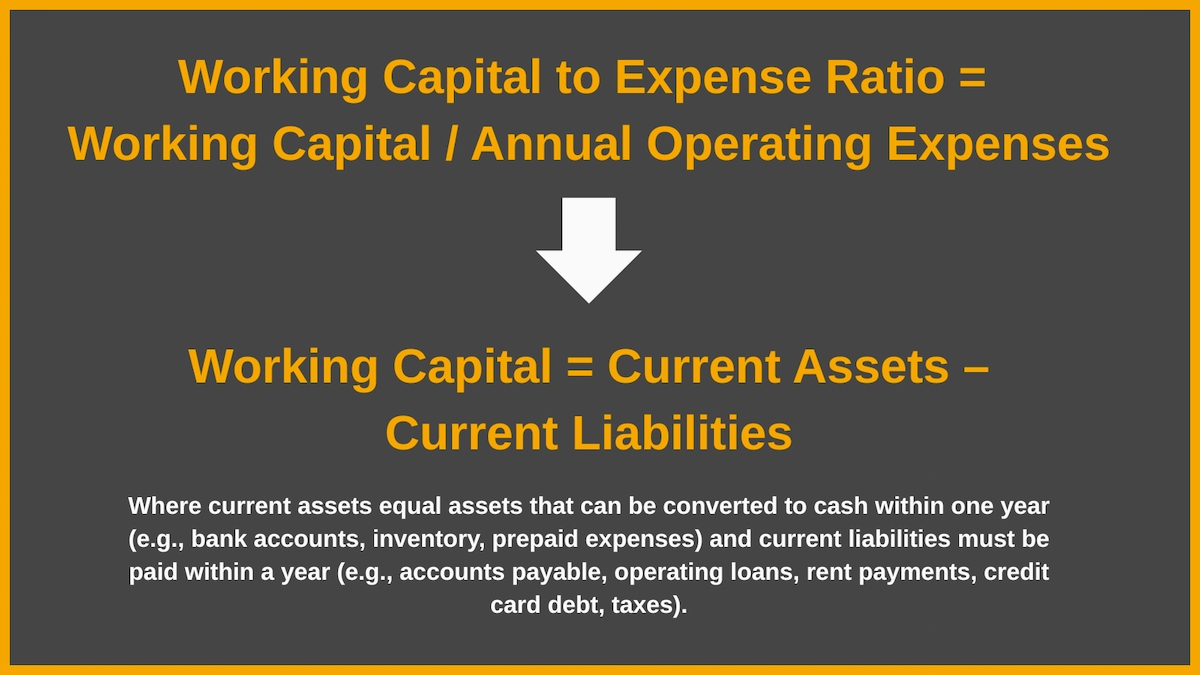

First, calculate your working capital:

Working Capital = Current Assets – Current Liabilities

Where current assets equal assets that can be converted to cash within one year (e.g., bank accounts, inventory, prepaid expenses) and current liabilities that must be paid within a year (e.g., accounts payable, operating loans, rent payments, credit card debt, taxes).

Working Capital to Expense Ratio = Working Capital / Annual Operating Expenses

Some financial analysts use these same measures to calculate the Current Ratio, which compares current assets to current liabilities.

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

The current ratio can be used to measure short-term viability, but Lieverse and Macfie both find comparing working capital to annual expenses more intuitive.

A “good” ratio for you depends on your strategy.

If working capital is equal to annual farm expenses, your ratio is 1:1. “Your farm can finance next year’s crop,” Macfie says.

Many farms’ ratio is less than one.

“Some farms put all of their working capital into more land and machinery, and that’s how they grow.” These farmers are using cash-on-hand to finance expansion, whether it’s land, machinery or equipment. “That works,” Macfie says, “until it doesn’t.”

If the working capital to expense ratio is too low, the farm will be short on cash, perhaps to the point of financing short-term inputs with expensive retail credit.

“Once you maximize retail credit, there’s really no options besides refinancing or selling land,” Macfie says.

The safest approach is to keep your working capital to expense ratio well above 1:1. But this plan may not keep your money working hard enough. Maybe some capital could replace depreciated assets or repay high interest loans.

Macfie visualizes this ratio as a teeter-totter, with managers balancing cash on hand against re-investments. “The hard part is that balance.”

What does Macfie advise? “The easy advice is 50 percent,” Macfie says, noting that the ideal situation will always vary from farm to farm according to your strategy and your industry.

2. Debt service coverage ratio (DSCR)

What it measures: “Bankers are concerned that you can repay your debts,” Macfie says. “Why would you loan more money to someone who hasn’t shown recently that they can service debt? If your three- or five-year history doesn’t show you can service more debt, why would I give you more debt?”

The debt service coverage ratio compares your recent annual income to the size of your debt.

How to calculate it:

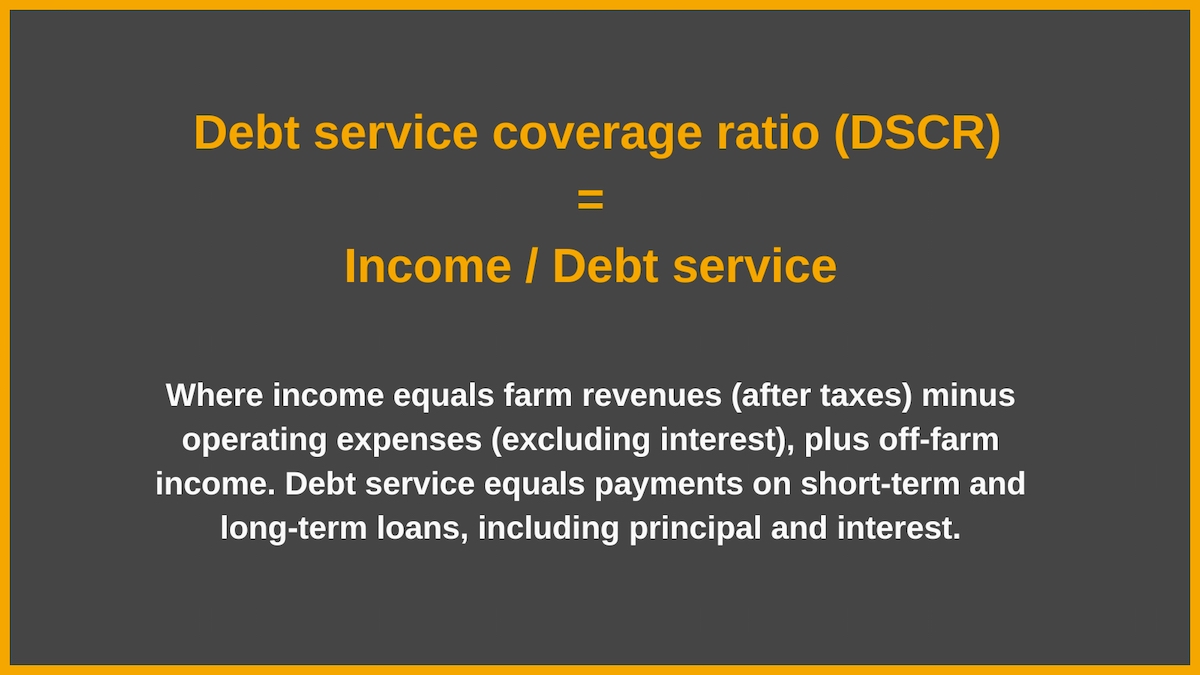

DSCR = Income / Debt Service

Where income equals farm revenues (after taxes) minus operating expenses (excluding interest), plus off-farm income. Debt service equals payments on short-term and long-term loans, including principal and interest.

What is a good ratio? If your debt service coverage ratio is 1:1 or higher, you have enough income to pay your debt. A higher DSCR indicates higher profitability relative to debt.

Lieverse would like to see a ratio a little higher than 1:1. “Ideally above 1.25, but it’s very heavily dependent on the industry.”

Rising interest rates will increase your debt costs, decreasing your DSCR. You could raise your DSCR by restructuring or paying down debt.

A manager focused strictly on DSCR might turn down growth opportunities that require debt. The ideal ratio is the number that fits your strategy.

3. Debt to equity ratio (DER)

What it measures: The first two indicators on this list are more important to banks, says Lieverse, as they’re more relevant to day-to-day operations. The DER shows your long-term viability. “If there was a profitability concern, long-term, how could the producer sustain themselves?”

How to calculate it:

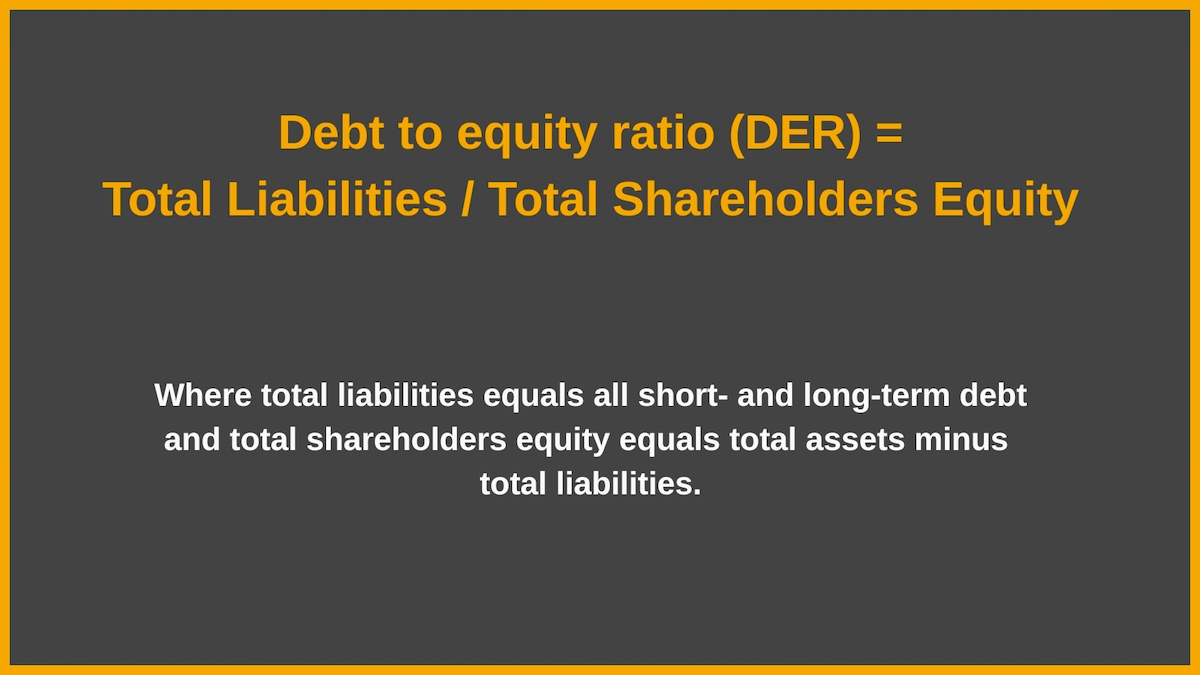

DER = Total Liabilities / Total Shareholders Equity

Where total liabilities equals all short- and long-term debt and total shareholders equity equals total assets minus total liabilities.

Corporate balance sheets usually show long-term assets such as land and buildings at purchase price (book value). Updating asset values to current fair market prices makes the results more realistic (and probably more comforting).

What is a good ratio? A low DER indicates a farm with flexibility to borrow money if opportunities arise. A farm with a high DER may have taken on debt to buy more land or may be in a financially vulnerable position.

While long-term customers may have some leeway, Macfie says, “Banks don’t care if you’re sitting on a bunch of land equity if the farm hasn’t been profitable in a few years.”

You could raise your DER by selling land or equipment to repay loans. But unless downsizing is part of a long-term strategy, it may not be the ideal solution for you or your lender.

Take action to control financial indicators

Many aspects of farm financials are outside your control. If you find yourself with less-then-perfect ratios, here are four steps to take:

1. Develop good working relationships: “You can’t control the weather, but you can control having a good relationship with your banker and your accountant,” Macfie says.

2. Timely financial statements: Your financial indicators may not be great, but they can still be timely. “You can control getting your bookkeeping to the accountant on time, so they can get it to the banker on time,” Macfie says.

3. Check your corporate year end: Ratios change depending on where you are in your annual production cycle. For example, if you’re a grain farmer with a July 31 year end, “the bank is testing your balance sheet at the worst time of year.” Your Working Capital to Expense ratio will be low, since your current assets are still out in the field. Re-calculate that ratio on October 31, when your barley is in the bin.

4. Cut costs: If most of your financial indicators are grim, it’s time to look at your operation. “There are efficiencies to be found across the board on land, machinery, labour, agronomy and other operating expenses,” Macfie says. “Keep looking.”

Looking to the future

Lieverse describes herself as a “disruptive agricultural banking leader.” But even innovative bankers still calculate ratios.

“Banking has a bit of tradition to it,” she says.

Most of Lieverse’s clients are operational experts. “I very seldom stop at an operation where a producer doesn’t know their costs of inputs down to the acre and cannot articulate soil health with a degree of expertise.”

But some farmers have become experts in these areas at the expense of “soft side” business aspects. “Many farms have struggled in operational items related to finance and HR.”

When rising land prices create strong balance sheets, Lieverse says, “you can make mistakes and not really be forced to learn from them.” This probably won’t always be the case. “We’re going into a commodity cycle where margins are tightening. What are you doing to future-proof the farm?”

“Financial ratios are great because they tell us how the farm has done,” Lieverse says. “But what I’m equally interested in is hearing from producers about what they’re going to do. Financial ratios are about looking in the rearview mirror. But I know that operators are driving looking out the window ahead.”