Farming has been described as the backbone of civilization. Without the domestication of crops and livestock, society as we know it would have been impossible. So, since it’s so important, everyone knows what farming is, right?

If you ask a random group of people what farming is, and what role farmers play in society, you will get a wide range of answers. Unsurprisingly, though, the list will likely be topped by the idea that the primary role of a farmer is to produce food.

If you ask farmers why they farm, in addition to “feeding the world,” they will tell you of their love of the land, and how they are stewards of the soil. They will define farming by independence, hard work and self-sufficiency. Some will claim that farming is not only a job, but also a way of life. Others will emphatically argue that modern farming is no longer a lifestyle, it is a business.

Read Also

Farm & Family – Feb 27 edition

Last week, we highlighted part one of a two-part series by GFM associate digital editor Geralyn Wichers about why you…

At some point, most will say that there is also pride in being a farmer, the sort of almost patriotic passion that Paul Harvey’s speech “So God Made a Farmer” verbalizes.

But are these romantic notions? Do the images that farmers and society have of the industry truly reflective of modern farming? Are broad acre farmers really feeding the world, or are we just supplying commodities to be processed into foodstuffs? Are we truly stewards of the land when we knock down every tree and drain every pothole so that large modern equipment is not impeded in our quest to maximize commodity production?

Are we really self-sufficient, independent caretakers of the world? It sure doesn’t feel like it when I look at my budgets for fuel, fertilizer and equipment replacement this spring.

Are the common definitions of farming obsolete? In fact, it makes me wonder: do the ways we think about agriculture and farming limit our future opportunities and business potential?

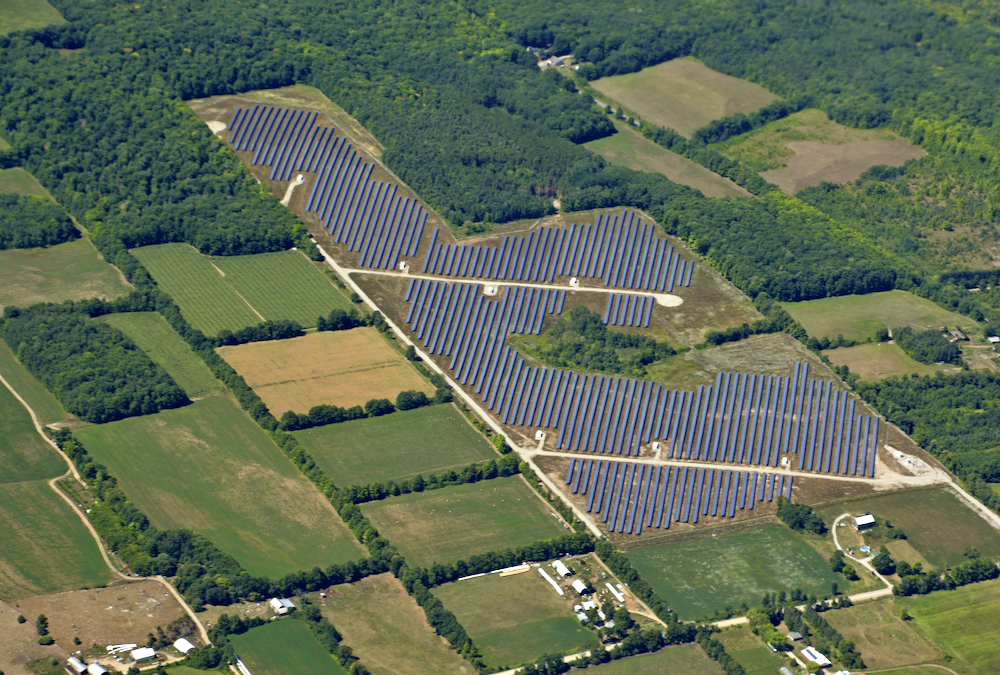

These questions arose as I listened to a group of farmers complaining about a solar energy project. They claimed the solar panels were a blight on the landscape and that placing them on dry prairie rangeland would threaten world food security. The conversation went on about the foolishness of solar energy in the first place.

And then it hit me. The one thing that all farmers — livestock, grain, vegetable, fibre producers, etc. — have in common is that farmers are harvesters of solar energy. Every crop we grow or pasture we graze converts solar energy into food and fuel for society’s needs. Farmers are more dependent on renewable solar energy than anyone. Farmers, in fact, are renewable energy harvesters.

It has only been in the past century that modern agriculture has become addicted to fossil fuels to power equipment and provide many of the fertilizers and inputs that we farmers rely on today. Before then, farmers grew their own fuels to feed the beasts of burden used on farm operations. In much of the world this is still the case on small-hold farms.

Then, a cheap fossil fuel-based economy provided farmers with equipment, fuels, fertilizers, etc., which allowed farm operations to expand and produce more. In fact, modern farming is so productive that we easily feed the world — or at least everyone in the world that can afford food. We are so productive that the cost of food has continually dropped. Commodity prices over the last century have not even kept up with inflation. Successful farm businesses have not been built on high commodity prices, but on increasing production to overcome rising costs and inflation.

Perhaps the best indicator of farm productivity is our market. No longer are we just feeding the world. Farmers are now harvesting solar energy to fuel the world too. In 2021, the Center for Sustainable Systems at the University of Michigan’s “Biofuels Factsheet” Pub. No. CSS08-09 documented how, in the 2019-20 crop season, 35 per cent of the corn grown by U.S. farmers — a whopping 4.9 billion bushels — went for ethanol in the 201 ethanol refineries in operation in the U.S. Another 91 biodiesel plants are a major market for soybeans, canola, corn oil and livestock fats and grease.

The biofuels market has become critical to supporting the prices of all agricultural commodities. A 2006-08 study of the impact of biofuels on corn prices revealed that biofuels had raised corn prices by 20 to 50 per cent, wheat prices by one to two per cent and vegetable prices by 10 per cent.

However, that market is not without problems, and there are more clouds on the horizon. First and foremost, biofuels continue to be subsidized by governments through tax incentives and credits. And demand is ensured by mandated biofuel content standards.

More troubling is much of the corn grown for ethanol production in the U.S. Midwest is grown under irrigation. In Nebraska, for example, 780 gallons of water are required for every gallon of ethanol produced. Midwest aquifers and western rivers are being rapidly drawn down, especially by agriculture, while both rural and urban demand for water is increasing.

Current fertilization practices needed for high-production agriculture are also having an environmental impact. Fertilizer runoff is resulting in an average of 5,408 more square miles of the Gulf of Mexico being classified as hypoxic every year, resulting in injury and death of fish in this area due to algae bloom fed by the flood of ag-based nutrients.

But even more worrisome, from a farmer’s perspective, is the movement away from fossil fuels due to climate change concerns. Future electrification of motor vehicles could have a significant impact on the biofuel market for farm commodities.

The bottom line is that farmers today are once again growing their own fuels. Instead of harvesting oats to feed the horses, we are now growing corn and vegetable oils to refine into fuels to be burned in internal combustion engines. We have reached a new equilibrium of food/fuel production on farms — as long as the trends in the demand for biofuels and environmental impacts of biofuels are ignored.

But if farmers truly are business oriented, they need to be looking now at alternative crops as humanity’s demands change with respect to fossil fuel use and farming practices.

Instead of farmers locking ourselves into the belief that farmers feed the world, let’s be honest about what farmers actually are: renewable solar harvesters. Let’s at least consider the possibility that many farm areas could switch from the growing of crops for biofuel energy to directly capturing the energy from the sun with solar panels.

Last September Bill Nussey published a thoughtful article comparing the benefits of corn-grown ethanol with solar panels. He calculated an acre of Iowa corn yields 551 gallons of ethanol. However, that same acre of Iowa land covered with solar panels would produce 198,870 kilowatt hours annually.

Based on average mileage for a gas-powered car, and for an electrical vehicle, Nussey claims the energy yield from the solar panel would propel an electric car 70 times further than the acre of corn-based ethanol.

In 2012, the USDA Agricultural Research Service compared the efficiency of solar panels with photosynthesis. The bottom line is that modern solar panels can convert about 10 per cent of the solar energy they receive into useable chemical energy whereas crop photosynthesis only converts one per cent. Today, new solar panel designs can reach up to 20 per cent efficiency.

The major drawback to solar energy capture is that plants store the energy they produce in seeds and plant matter. Solar panels do not store energy so some type of energy storage system must be developed for the energy that is produced but not immediately needed.

Many who are opposed to solar energy will also point to the high cost of solar panels. Yet they ignore the costs of labour, farm equipment, crop inputs, water, transportation, and processing needed to grow, harvest and convert that plant into a food or fuel that people can use.

The hardest part to argue against development of a solar farm is that companies are now willingly paying more to farmers interested in leasing their land for a solar production than farmers receive in crop land rental.

Without question, not all farmland is suitable or should even be considered for solar panels. But at the same time, if you consider that growing any crop is in fact harvesting solar energy, is it not appropriate to consider solar energy production as a potential “new crop” for your farm? If you live in an area of poor soils or an area that is consistently short of rainfall, could a solar farm be a way to preserve your farm and community?

History tells us that the introduction of the tractor was resisted by many farmers who continued to use horses for many years after tractors were introduced. Ignoring the potential of solar generation on farms may be just as detrimental to today’s farm businesses as ignoring tractors was when our ancestors had to decide whether to get on board with a changing world or stick with the old ways of thinking.

Society is demanding a transition from fossil fuels. As business leaders, farmers need to look for opportunities in change rather than just resist it.

Redefining what farmers do is the first step in not only finding new opportunities but telling society and governments that farmers are already doing what they are demanding. Farmers are the original renewable energy producers!