Thirty years ago, after the collapse of the commercial fishing industry, and before the First Nation of Kitasoo Xai’xais established its first fish farms, the community’s employment rate was around five per cent. People struggled to find purpose and hope, some turning to alcohol, and others, sadly, committing suicide.

Today, the community is thriving and celebrates that it has not lost a life to suicide in 18 years. It has also become a model for other First Nations communities interested in the salmon farming industry.

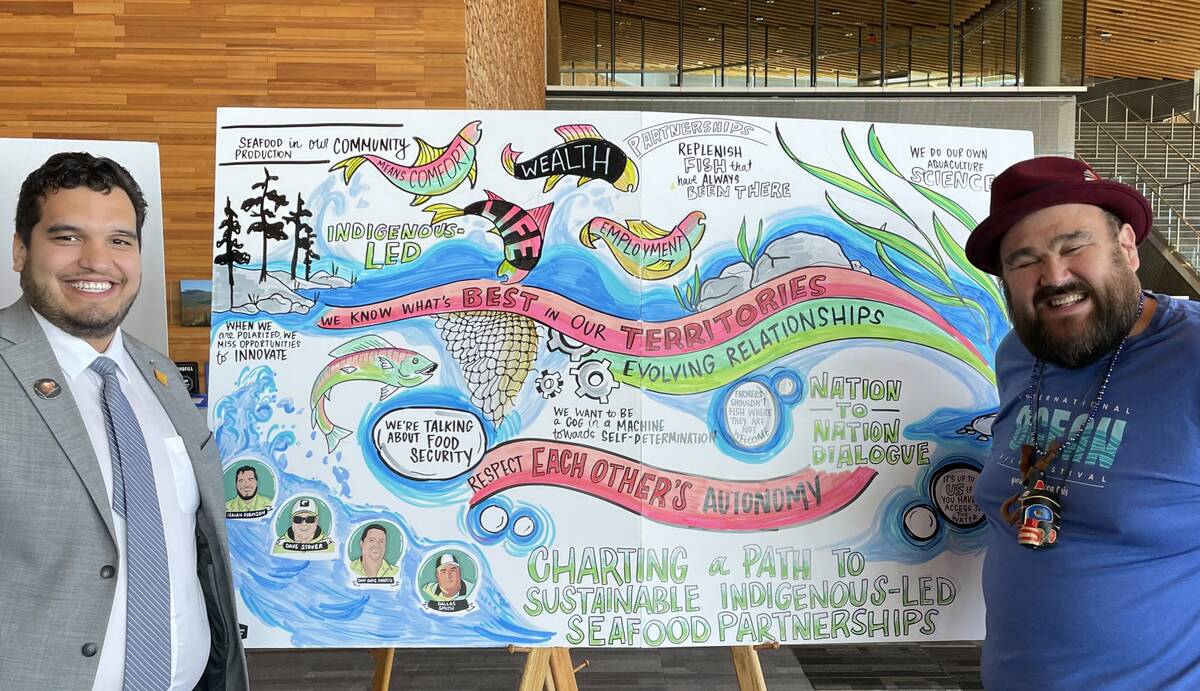

There are currently 59 salmon farms along the coastline of British Columbia, all operating in partnership with roughly a dozen First Nations on whose territories they are located. Even after a 45 per cent reduction in the number of salmon farms over the past few years, the sector still contributes $1.14 billion to B.C.’s economy and accounts for 4,500 jobs, according to the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association (BCFSA).

Read Also

Sibling squeeze part 6: The emotional stakes of a family legacy

The final instalment in a six-part series exploring the challenges of sibling conflict and the effect it can have on…

Some of the most successful salmon farms are located at Klemtu, home of the Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation, a remote community that can only be reached by boat or air, located on B.C.’s central coast around 500 km north of Vancouver.

In 1998, Kitasoo Xai’xais signed an agreement with a corporate partner, Mowi Canada West, part of one of the largest seafood companies in the world. The community was the first to sign an impact benefit agreement and to lease out tenures to ensure that Mowi would operate under their stewardship expectations.

The partnership creates jobs for Nation members and wealth for them and the community. Slightly more than half of its 450 population is employed in some aspect of salmon farming, as farmers, in the community’s fish processing plant or in other spinoff businesses that serve the industry.

“We now have a 99 per cent employment rate and 51 per cent of our economy is represented by salmon farming, which is worth about $3 million a year,” says Isaiah Robinson, CEO of Kitasoo Xai’xais Development Corporation.

Aquaculture is the fastest-growing food production sector in the world, supplying most of the world’s seafood.

And as demand for seafood continues to rise, a report by the World Bank suggests that aquaculture is shifting from a niche to a mainstream industry. Production could increase by 97 million metric tonnes a year, creating 22 million new jobs by 2050 — provided stakeholders capitalize on the $1.5 trillion investment opportunity in the sector over the same period.

Canada is uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth potential.

Aquaculture’s potential

“The dream of our previous leaders was to have one breadwinner within every household to ensure that there is balance and opportunity,” says Robinson. “The agreement (with Mowi) is strong, has strong environmental factors in it and it works extremely well for our people.”

The Nation is also working on building a science strategy with its business partners to monitor and understand all the effects of the salmon farming industry.

“As Indigenous people, specifically on the coast, salmon has sustained our people for thousands of years. We’re not trying to change that, we’re simply trying to enhance how everything can fit together,” says Dallas Smith of the Coalition of First Nations for Finfish Stewardship and member of Tlowitsis Nation.

“First Nations are bringing a balanced approach to this equation because not only are we developing salmon farm opportunities, we’re protecting watersheds for wild salmon. First Nations are both regulators and developers of this industry, and we think that we can take this to the next step.”

But in recent years, opponents of salmon farming have suggested the practice harms wild salmon populations and has a negative impact on the marine environment. They have gained the ear of governments, resulting in the recent closure of several B.C. salmon farms.

However, recent data from long-term monitoring of areas where salmon farms have been removed show that removal of salmon farms had no effect on the incidences of harmful diseases and parasites, such as sea lice, on wild salmon populations.

At the request of First Nations, BCSFA also undertook a modern science review in 2023 that summarizes all the available research data about salmon farming in a format that is publicly accessible and easy to understand. The review is available at www.bcsalmonfarmers.ca/science-review.

Technology gives a boost to the industry

In an industry already highly regulated and monitored by both marine and terrestrial regulatory bodies (including the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Agriculture Canada) advances in technology and management practices are making salmon farms more ecologically sustainable and efficient.

“We work in a marine environment, so it has a lot of challenges,” says Brian Kingzett, executive director of BCSFA. “A large salmon farm is a high-tech oceanographic monitoring platform. It is similar to how traditional farms have weather stations measuring humidity and moisture. But a modern salmon farm is seeing about one million oceanographic data points a day.”

Analysts process the data and cross-reference it with satellite information to produce a marine weather forecast that predicts expected ocean changes over the next five days in terms of oxygen, temperature or other conditions that might affect the fish. This information is used to adjust feeding programs.

Most of the agreements between aquaculture companies and First Nations include having a biologist on farms to provide environmental oversight and First Nations representatives, such as guardians, to review data and compliance. All farms have in-house or contract veterinarians and many use remote-operated vehicles to inspect and sometimes clean nets.

Farms use underwater cameras and AI to monitor fish health and ensure feed efficiency because 40 per cent of the operating costs of a salmon farm is feed. A new technology coming soon will use underwater cameras to monitor individual salmon.

“The cameras look at the spots on the salmon that essentially become each salmon’s individual bar code,” Kingzett says. “Every time a fish swims by that camera it calculates how big the fish is and a whole series of veterinary aspects regarding its health and that all goes into a database.”

Monitoring disease and environment

Disease monitoring and prevention is a high priority on fish farms with a focus on screening for organisms, culling infected fish, vaccinating, increasing nutrition and decreasing stress.

“For every 100 fish on a farm that start the year, three will die of an infectious disease over the course of a year,” says senior fish pathology consultant Dr. Gary Marty.

B.C. salmon farms are monitored for disease more than any other livestock production in the world. Fisheries and Oceans Canada veterinarians oversee disease audits on nearly every farm every quarter. Over the course of a year, they examine and test 800 fish that have recently died on farms. Any disease outbreaks that result in mortality above a certain level must be reported by a licenced salmon farm veterinarian to government regulators.

“Independent fish health professionals have a strong consensus from the data that salmon farms of B.C. are not a significant threat to wild salmon,” says Marty. “Some of the anti-aquaculture people believe that salmon farms are a significant threat. My recent publication (Pathogens from Salmon Aquaculture in Relation to Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon in Canada: An Alternative Perspective) provides strong evidence that that’s not the case. The risk is there but the impact is no more than minimal.”

Pacific salmon catches by all countries have been at historic high levels for more than 20 years, and the abundance of some species, such as chum salmon, are declining. Some scientists think the recent declines relate to ocean warming but the “how” is not yet fully understood.

“We are seeing changes in salmon abundance in all countries that we have never seen before and we have been studying salmon for a hundred years,” says retired marine biologist, Dr. Richard Beamish. “My interpretation is that these are dynamic, large-scale changes that almost certainly are related to ocean changes because of global warming, and these ocean changes are changing food production for all salmon, and that’s changing the traditional capacity of the ocean to support salmon.”

The future of fish

In addition to providing socio-economic value, aquaculture has a vital role to play in terms of global food security. The World Bank report indicates that aquaculture plays an essential role in feeding a growing population, fuels economic growth and reduces the food sector’s greenhouse emissions.

“In B.C. we are down to four companies and 59 operating farms that are producing over $1 billion worth of salmon,” Kingzett says. “Norway, in comparison, has over 200 companies, 1,220 salmon farms, tens of thousands of employees and exports $17 billion worth of farmed salmon. So that is our opportunity to help feed the world with low carbon protein and take advantage of our sustainability and our partnerships with First Nations to be able to be a major economic driver and food producer.”

Most of the salmon produced in Canada is currently exported to the U.S. while Canada then imports salmon from other countries such as Chile and Norway to meet domestic demand.

“That’s leaving Canada at a trade deficit, so there is a huge potential for growth,” says Smith.

And aquaculture is learning a thing or two from land-based agriculture, especially when it comes to engaging future generations.

“Globally, this is the fastest growing protein sector in the world and it’s embracing high tech, so it presents a massive opportunity for young people that are tech savvy, want to work in the environment, want to work outdoors and in rural areas,” Kingzett says.

“We are trying to learn from some of the more established organizations like the B.C. Agriculture Council who really involve youth,” Smith says. “You think of 4-H and all the other great programs to keep people farming; we’re trying to instill a lot of those values now and get the message out that it’s not just working on the farms that’s the great thing about aquaculture.

“We also need biologists, chemists, accountants, so the more that we can grow the economy around a sustainable industry like this the better off our communities are going to be because they’re not sunset jobs.

“These are jobs that will go on in perpetuity if we do it properly.”