In a province where only two per cent of its land is suitable for agriculture, Quebec has been losing cropland to the province’s expanding cities at the rate of 12 football fields every day, and it has been losing farmland at that speed for nearly three decades.

Even now, says Quebec’s UPA, its main farm organization, the province has only 0.24 hectares of arable land per person, the lowest in North America.

And more pressures loom.

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

The past

Quebec has long favoured careful management of its agricultural lands.

In 1978, on the heels of almost two decades of an economic boom that saw mass migration to urban and suburban centres, the provincial government implemented the Loi sur la protection du territoire et des activités agricoles (LPTAA — Act Respecting the Preservation of Agricultural Land and Activities).

More than 20,000 hectares of quality soil were sacrificed to urbanization surrounding the city of Montreal between 1964 and 1975. To stymy land speculation and unchecked development of prime agricultural land, the Commission de protection du territoire agricole du Québec (CPTAQ — Commission to Protect Agricultural Land) was also established in 1978 following enactment of the LPTAA.

The CPTAQ’s mandate was, and is, to protect Quebec’s farmland through application of the LPTAA. It is responsible for reviewing and approving (or refusing) requests for authorization to use farmland for non-agricultural purposes. When assessing requests, the CPTAQ follows a list of 10 mandatory and two optional criteria. It also takes into consideration any distinctive regional characteristics while acknowledging the importance of the land’s sustainability for future generations.

“In Quebec we talk a lot about food autonomy and security,” says UPA president Martin Caron. “The most important tool we need to achieve those goals is our agricultural land. Having the lowest ratio of land to citizen… well, we had better think twice about protecting our farmland, because that’s our pantry.”

The present

The battle to protect farmland is about more than just losing it to urban sprawl — although that is a very real and considerable challenge.

“We have arrived at a critical moment of increased density of urban sprawl — and it will require a concerted effort to protect our farmland,” says Caron. “For example, we shouldn’t just be building one- or two-storey houses, but several storeys if we want to decrease urban sprawl and its impacts on agriculture.”

Caron notes that a city’s impetus to expand is because it’s increasingly difficult to obtain revenue from land taxes. “The more households they have, the more revenue they get, but the more services are required in terms of infrastructure to support those households, and so they have to find a way to pay for that infrastructure (which means adding yet more houses). It becomes a vicious circle,” he says.

Then there’s the phenomenon of “non-agricultural use.” Land is typically zoned either green, meaning it’s for agricultural use, or white which is for non-agricultural use, e.g. residential, industrial and commercial. “But the green zone is increasingly being used for non-agricultural activities while remaining zoned as green,” says Caron. “Regional County Municipalities (RCMs) and land developers are using this loophole and, at last assessment, the UPA calculated that 61,000 hectares were lost from the green zone this way.”

Caron says that in most cases non-agricultural applications are usually for infrastructure like hydro lines, so the land is not de-zoned, but it is being used for non-agricultural purposes. “We’re seeing this occur more often in recent years and it has a real impact on our agricultural land base,” says Caron. He says it also skews the reality and severity of the situation. “So, the government tells us, ‘It looks like we haven’t lost that much in the green zone after all’; however, the CPTAQ keeps track of these numbers and we know that 61,097 hectares in the green zone have been sacrificed to non-agricultural use.”

As Country Guide covered in our November issue, steep climbs in farmland values are also having an impact on ownership. This is an important concern for the UPA. “Farmland is typically purchased and owned by three types of people: agricultural producers, producer-entrepreneurs and speculators,” says Caron. “More and more we have people buying farmland on speculation. We’ve seen this for the past few years when interest rates were low. As farmland values increased, its value became much higher than interest rates. So, we saw a lot of farmland being purchased by non-farmers, i.e. speculators, because a year after they bought it, that land’s value would increase by eight or 10 percent.”

The UPA is pushing for a law regarding land speculation. “If we can’t have a land registry that adequately traces all real estate transactions (of who is purchasing farmland), then maybe we can take other actions that bring us to the same end goal, or that help diminish the negative impacts of current practices (on our agricultural lands),” Caron says optimistically. “The government incorporates food sovereignty into many of its provincial plans, and with the current public consultation (see more about this below), it’s an opportune time for us to make demands.”

Caron says that there’s a concentration of land speculation activity in certain regions of the province. “Speculation combined with increases in the price of farmland is making it difficult for the upcoming generation who want to buy land,” stresses Caron. “It creates a situation where the land’s value is not based on its agronomic value. If the value of land is not based on its agronomic value, but rather on its market value, it’s difficult to make it profitable over 20-25 years (the length of a traditional loan).”

To compound the problem even more (yes, there’s more!), Caron says there’s still a lot of work to do around protecting agricultural activities. “This is important because currently land can still be classified in the green zone, but there are limits around the activities occurring on it. For example, you can’t use certain pesticides, or some types of work can only be done between this-and-this date. The green zone was set up specifically for agricultural activities, but the work being carried out in it is being questioned and, currently, villages and municipalities have the right to legislate agricultural activities in their jurisdiction. This is a huge slap in the face for producers, like their profession and their expertise is not recognized or is being questioned. They go to school to become professionals in agriculture, but then they’re being told they must do their job this way, not that way.”

The future

Quebec’s agriculture ministry is hosting a public consultation which began last June (2023) and runs until June 2024. The Consultation nationale sur le territoire et les activités agricoles — Agir pour nourrir le Québec de demain (Provincial Consultation on Agricultural Land and Activities: Act Now to Feed the Quebec of Tomorrow) consists of three phases: agricultural land, agricultural activities, and landholdings and ownership.

The goal of the consultation is to learn more about the types of activities occurring on agricultural land and about ownership in terms of who should be eligible. Input from the consultation process will be used to overhaul the laws that currently govern provincial farmland protection.

During the current third and final stage of the consultation, the UPA is putting pressure on the provincial government regarding the issue of who can purchase farmland. “The UPA wants to enact some measures but correct others. For example, we really must enact some kind of policy or regulation that prevents investment funds from purchasing our farmland. As we’ve seen recently in Saskatchewan, what happens when those types of entities purchase land is that when they resell, no one can afford to buy that land, so it just goes into the hands of another consortium.”

Caron says the UPA has already proposed that the government cap the number of hectares someone could purchase. “We suggested a cap of 100 hectares, meaning that a person would not be eligible to purchase more than 100 hectares per year.” (See ‘Acquisition of farmland in Quebec by non-residents’ at bottom)

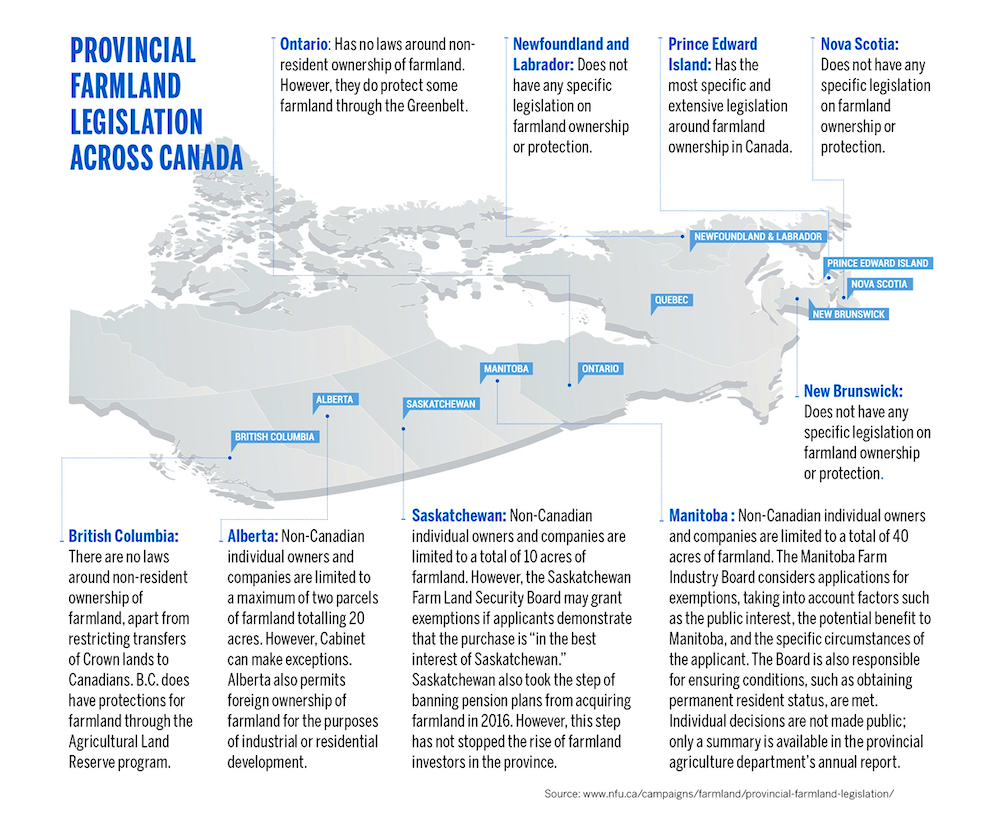

Quebec has a registry of non-residents or non-farmers who purchase land, but, Caron asks, how can we manage it better? “Elsewhere in the world, and here in Canada in Prince Edward Island, for example, if you’re looking to purchase land as a non-farmer, you must declare whether you have shares in a company that has ownership of that property. That’s what we’re looking to avoid in Quebec, having a situation where there’s a concentration of those types of people or companies (speculators). Land is the most important tool agricultural producers require to practice their profession; to not have that tool makes things very complicated.”

One of the tools the UPA, along with a few other organizations, has developed is the “fiducie foncière”, a property trust. It works like this: a producer interested in selling their land can sell it to the trust and then rent it for a 40-year term. This ensures that the land remains in agricultural use. After the end of the term, the lessee has the option to purchase, or they can renew the lease.

Another challenge has been the aforementioned “loophole” of “demandes à portée collective” (applications of collective scope), otherwise known as Article 59. This provision allows RCMs and communities to plan for long-term residential needs in agricultural zones.

The intention is to approach land development in a way that establishes clear rules around the development of residential zones in the green zone by applying a sustainable development lens while acknowledging protections for agricultural land and activities.

“About two-thirds of RCMs have used this process, for example to build houses in zones that will have less of an impact on agriculture,” Caron says. “But there are tools that currently exist for municipalities and the agriculture sector to collaborate, to find that middle road of solutions. To us it’s clear that requests must pass through the tools we already have available, for example the CPTAQ, which is impartial. Requests most certainly should not bypass the checks and balances currently in place.”

The UPA also has several concerns with the Quebec government’s Plan Nature 2030, a far-reaching consultation and planning project aimed at determining how best to preserve and protect 30 percent of the province’s biodiversity (terrestrial, marine and coastal ecosystems) by 2030.

In November, Caron stated that “the protection of biodiversity… must not be done to the detriment of agricultural activities” and that the UPA will push for consistency between federal and provincial biodiversity protection plans, Quebec’s Sustainable Agriculture Plan, and Ottawa’s Agricultural Climate Solutions Program.

Food movements as well as world events such as a pandemic, wars, climate change and other food system disruptors are altering food production systems. The key is to find systems that are sustainable and beneficial to all stakeholders.

Caron says that ultimately, we must reinforce laws and regulations that protect agricultural activities and land and add laws that will limit the scope of land speculation, including implementing a thorough land registry.

“Citizens are beginning to see the importance of this matter,” he says. “When you keep reinforcing the facts — that is, less than 2 per cent of our land is available for agriculture and that there are only 0.24 hectares available per citizen — and then not only farmers but other organizations like the David Suzuki Foundation, Heritage Montreal and many others are telling consumers the same thing, it becomes very real, especially after the pandemic. No one actually went without food during the pandemic, but it really made consumers realize how precarious the food system is.”

“One of the main goals of the LPTAA was to ensure that there is a future for our agricultural lands and that those lands would stay in the hands of those working in the agriculture profession,” says Caron. “But there are those who become agricultural landowners and don’t cultivate it (e.g. those who buy 10 hectares or less). We’ve seen elsewhere that laws have been enacted which mandate landowners to cultivate that land. This decreases the pressure on farmland availability and price — but this requires everyone to mutually agree on an approach to agricultural land management.”

And that — to mutually agree on a solution that benefits everyone — is a tale older than Quebec.

Acquisition of farmland in Quebec by non-residents

The Act Respecting the Acquisition of Farm Land by Non-residents lays out the rules for who can purchase agricultural land and how much.

Non-residents of Quebec (including residents of other Canadian provinces) are limited to owning four hectares (about 10 acres) of farmland unless they demonstrate intent to become residents and establish themselves within four years.

A resident is considered a natural person who is a Canadian citizen or a permanent resident within the meaning of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and who has lived in Quebec for not less that 1,095 days during the 48 months immediately preceding the date of acquisition of farmland.

A legal person is a Quebec resident if it is validly constituted (regardless of the manner or place of constitution). In the case of a legal person with share capital, more than 50 per cent of the voting shares of its capital stock must be owned by one or more persons resident in Quebec and more than one-half of its directors must be natural persons resident in Quebec. In the case of a legal person without share capital, more than one-half of its members must be resident in Quebec. Furthermore, the legal person must not be directly or indirectly controlled by one or more non-residents.

Non-residents cannot, directly or indirectly, make an acquisition of farmland without the authorization of the Commission de protection du territoire agricole du Québec (CPTAQ). Non-residents cannot add more than 1,000 hectares per year to their holdings, but they may exceed this limit with permission from the CPTAQ. An application to purchase land must be accompanied with an affidavit declaring the reasons for the acquisition of the land, the intended use and that the applicant intends to settle in Quebec.

Before the CPTAQ grants permission, it will examine such factors as the intended use (whether the land is suitable for cultivation or raising livestock); the impact the acquisition will have on the price of farmland in the region; the effects of the acquisition or projected use on the economic development of the region; the development of agricultural products and the development of underutilized farmland; and the impact of land occupancy.

The CPTAQ’s decisions are final and without appeal. Furthermore, if a person is found to be contravening any provision of the act, the CPTAQ can issue an order to “cease and desist” within a set timeframe. If the person fails to comply, they may be ordered to divest themselves of the land within six months of the date of the decree.