The second that Mark and Bobbie Bratrud started telling people they were done farming, the news travelled faster than a Saskatchewan wind. “It was a rotating door through our house,” Bobbie Bratrud says. “Everyone was coming by to ask, ‘are you guys okay?’”

Mark recalls three of the most common rumours: “Somebody’s sick, you’re getting divorced, or you’ve gone bankrupt.”

None of those were true. “People can make the decision to stop farming for good reasons,” Bobbie says.

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

Still, while the Bratruds were happy with their decision, they knew it’s unusual.

It’s not common for successful, relatively young farmers (Mark’s 49 and Bobbie 47) to exit the industry while they’re making a profit. Especially if they’re farmers on a fourth-generation family farm, with three kids — two girls in university and a son still in high school.

But the Bratruds chose their own exit for their own reasons, so none of the gossip bothered them.

Though, Mark admits, “Maybe it bothered me a little bit.”

The truth is that Mark and Bobbie Bratrud decided to leave farming while they were in a strong financial position. Now they’re putting their assets to a different use while they step back from their hectic life and try out some new roles. They’re confident they’ve made the right choice, and willing to talk about how they made their decision.

- READ MORE: The dark market of farmland rentals

Building up the family farm

After they’d both spent a few years working in the ag industry, Mark and Bobbie moved into the farmyard where Bobbie grew up, a few miles north of Weyburn, Sask. This was “home” for Bobbie, but a long way from where Mark grew up, near Edmonton.

They built up their farm while they both worked at off-farm ag jobs. “We didn’t give up our outside farm incomes until we got to a point where we really felt comfortable,” Mark says. In 2010, they took on debt to buy more land of their own.

While they were building up the farm and working, they were also raising their three kids who were all very involved with sports, school and friends. Mark and Bobbie volunteered a lot of their time in the local community, helping to run programs from figure skating to 4H when they weren’t driving their kids to the rink or to lacrosse tournaments.

By 2022, the Bratruds were growing grain, oilseed and pulses on 5,500 acres of land, 2,300 of which they owned. Like most farmers these days, they were having a hard time hiring long-term farm help. Bobbie’s father and uncle liked to help out during seeding and harvest, but Mark and Bobbie wanted someone to share the workload year-round. They tried many options, from local young people to foreign workers, but finding the right fit for their farm was a real obstacle. Mark and Bobbie were doing most of the farm work themselves.

That spring, they had high hopes that their newest farm employee would be the person they’d been looking for, and their labour problems would be solved. When that didn’t work out, Mark and Bobbie were looking ahead at another summer of waking up early to do all the spraying with no time to spend at the lake with the kids. “We were running these crazy, stupid hours,” Bobbie says.

That’s when things came to a head.

“There’s never one reason why you make a big life change,” Bobbie says. “But we were really burned out.”

They had done the analysis. “It felt like we were going into uncertain times,” Mark says. Local land prices were hitting record highs. Farm machinery was not only expensive, it was almost impossible to even find the equipment you wanted to buy. Grain prices soared when Russia invaded Ukraine, but how long could those high prices last?

Mark and Bobbie have told this part of the story so many times that they tell it together now, finishing each other’s sentences as they explain it together.

The summer of 2022 wasn’t the first time they had considered what life would be like if they weren’t farmers. But that summer, skyrocketing grain prices, a good-looking crop in the field, and considerable values for land and equipment all worked to solidify the decision.

“We could be out of debt. We could pay all the taxes and own our land, and just step away from this madness for a while,” Mark says.

“And that was it,” Bobbie chimes in.

They both laugh, and Mark says, “There was no turning back.”

It’s not that they didn’t love farming. “We really have been all-in on this farm,” Bobbie says, “which you need to do to make a successful farm. We don’t regret that.”

But she remembers what it was like before 2022. “Everything revolved around this farm. We’ve been very successful. We’ve enjoyed it. But — is there another way to look at life?”

That July, they tendered their land for rent for the 2023 growing season, giving potential renters plenty of time to make cropping and input plans. But they also kept their options open, limiting their land rental contracts to three years. “We can always get back in,” Mark says.

Then they started selling a lot of their equipment on their own. “It was just very, very easy,” Mark says. “We would list something and within a day it was gone.”

Once the 2022 crop was in the bin, Mark spent nine months working in lending at the Weyburn Credit Union. “I hauled all the grain,” Bobbie says.

“Now we have to see what we want to do with our lives.” Bobbie says.

It’s all about timing

Before the summer of 2022, the Bratruds had grown good crops for a few years in a row. They were already in a strong cash-flow position, and 2022 brought another profitable crop. This was a chance to exit the industry from a position of strength. “The opportunity doesn’t come around every year,” Mark says.

- READ MORE: The lease-back business of farmland

With none of their children showing a strong interest in taking over the farm, Bobbie says, “Probably, we were going to be making this decision in 10 years anyway.”

This situation gave them a lot of freedom. “You don’t often get the opportunity to do it when you want to do it and how you want to do it,” Bobbie says.

They also knew the good times might not last. Mark was forecasting volatile times ahead, with rising interest rates, increasing input costs, and an inevitable decrease in crop prices.

The past comes back

Mark’s outlook on risk management was formed when he was growing up on his family’s Alberta farm. “My dad struggled through the ’80s,” Mark says. “He took a big hit during the major interest rate changes. He didn’t lose everything, but he lost part of his farm and he had to change careers.” Mark was only 10 when they held a farm auction, but he hasn’t forgotten the experience.

When inflation and interest rates started rising in the early 2020s, Mark saw similarities to the ’80s.

Mark’s father never went back to full-time farming, but he did well in other areas. When he passed away in 2000, Mark inherited cash that helped the Bratruds buy their first half-section of land near Weyburn, and also gave them the opportunity to partner with Bobbie’s father and begin their farming career.

Looking ahead at a potentially rocky future for farmers, Mark’s realized how important it was to him to protect his father’s legacy. “I was not prepared to squander that away when it felt like we were going into risky times.”

But what about the family?

The Bratruds’ lives were already changing by 2022, with their two daughters going to university away from home. But even from Saskatoon, it’s obvious to the girls that their parents have more time. “They’re starting to appreciate that when we say we can do something, we actually show up,” Bobbie laughs.

Mark and Bobbie have had a lake cabin for years, but now they have time to use it. They can relax and appreciate their view of the water from the deck while they drink their morning coffee, rather than worrying about what’s going on at home.

Looking back at their decision, the only time the Bratruds show any sign of regret is when they talk about the years when they put so much work into the farm that they had trouble making time for family.

Most of Bobbie’s relatives live nearby, but their farm is an eight-hour drive from Mark’s extended family. Under the time pressures of farming, they missed getting to know young nieces and nephews and spending time with aging aunts and uncles. “That was a big thing for Mark. He’s missed a lot,” Bobbie says.

Mark remembers missing a family funeral because they didn’t feel they could take enough time away from the farm to make the trip. “You feel like you can’t go for three days,” Mark says. There’s always something pressing on the farm, especially during the growing season.

Across the industry, farmers are making more efforts to balance work and life than most of the previous generation of farmers ever imagined. But when farm work is urgent, it’s hard to walk away. “It’s easier to stay home and work,” Bobbie says.

Mark and Bobbie’s kids are old enough now to understand how much their parents sacrificed to be successful farmers. They’re happy that when their kids were growing up, their friends’ parents were mostly also farmers, doing the same thing. Now, Bobbie laughs, “they’re getting to know people that aren’t from farms!”

“I think we actually turned them off from farming with our obsession with the farm,” Mark says. He’s joking, but it’s the type of humour that starts from a kernel of truth.

What’s next?

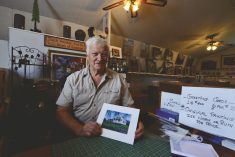

Mark and Bobbie are still busy, even without the farm. Bobbie is working as freelance consulting agronomist, and Mark has launched a new consulting company, Coyote Business Strategies, working with farms and small businesses on cash-flow planning, credit counselling, and general farm consulting.

They’ve also started a farm equipment rental business. They’d considered this idea years ago, when they’d had difficulties finding equipment to rent for their own farm. “Do you buy a Pro-Till for three days of work?” Bobbie says. “We would’ve preferred to rent but it just wasn’t available. There’s a hole in the market.”

This business fills a local need and allowed them to optimize their tax situation after they sold farm equipment. “The opportunity was there, just for tax purposes,” Mark says. “We realized, if we ever want to do this, this would be the best time to do it.”

Running an equipment leasing business also keeps the Bratruds in a position to get back into farming in the future, even if just to farm the land they still own. “We’re still invested in the equipment game,” Mark says.

They haven’t run a splashy ad campaign, but word has gotten around about the Bratruds’ new business: Rent Pro Ag and Industrial. They’re busier than they thought they’d be, and have already bought construction equipment to expand their rental line. “We do see expansion in the future,” Mark says.

First, they have to decide how big they want this venture to become. “Are we going to have business hours on the farm, or bricks and mortar in town?” Mark asks.

They’re not sure how much time they want to put into another business. “We can blow it up to a size where we can hire somebody, and then we’re back full circle to the same problem of finding help,” Mark says. Now that they’ve had a break from full-time farming, this makes them both laugh.

Know your options

The Bratruds believe that one reason many farmers don’t consider exiting the industry is that they don’t have the option. “There are a lot of people in their 40s or even 50s that couldn’t make this decision on their own,” Bobbie says. Many farm families are intertwined with other family members in their farm business, or still waiting for the older generation to make succession plans.

The Bratruds were farming independently, with formal arrangements in place with Bobbie’s father and no financial ties to other family members. This left them free to consider any options.

But the Bratruds’ wouldn’t advise every farm family to do what they’ve done. “It was right for us, but that doesn’t mean it’s right for the next person,” Mark says. “

Still, they think all farmers could consider the possibility of leaving the farm. “It doesn’t hurt to challenge yourself every once in a while, and go through the scenario. Go through the numbers and make sure you understand how it all works,” Mark says. Knowing you have the option to step back can bring a sense of freedom and opportunity, even if you decide that’s not what you want to do.

Since Mark and Bobbie have announced their decision, they’ve heard from lots of farmers who say they understand, and that they’ve had thoughts of doing something similar. “We all have the same confinements of running these crazy businesses,” Bobbie says. “It’s good to investigate your options.”

“The best time to exit is when you’re at a relatively high value in the industry,” Mark says. “A lot of people hang on too long.”

– This article was originally published in the Feb. 27, 2024, issue of Country Guide.