Could a more dangerous world inadvertently drive investments that benefit Canada’s agriculture sector?

Some analysts think so, but what investments will be considered “defence-adjacent” (e.g., infrastructure projects such as airports, ports, telecommunications, emergency preparedness systems and other dual-use investments which serve defence as well as civilian readiness) is uncertain.

Read Also

Sibling squeeze part 6: The emotional stakes of a family legacy

The final instalment in a six-part series exploring the challenges of sibling conflict and the effect it can have on…

This past June member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) formally pledged to increase defence spending from two per cent to five per cent of gross domestic product. For Canada, a founding member of the alliance, that means investing some $150 billion annually.

The bulk of that money, 3.5 per cent, will go towards military hardware, personnel and other materiel required for the defence of Canada and its allies. The remaining 1.5 per cent, however, is earmarked for a wider suite of defence-adjacent initiatives, such as improvements to critical national infrastructure, innovation processes and communications.

Improving Canada’s defence capacity through direct defence investments means addressing the need for more armour and artillery, ships, improved early-warning systems and communications, personnel and much more.

Though quite general, some of the defence priorities identified by the prime minister reflect similar requests stemming from many in Canada’s agriculture sector.

This includes a large coalition of agriculture groups which penned a letter to Prime Minister Mark Carney earlier this summer, asking his government to “prioritize transportation and trade infrastructure that support agriculture — including rail, port and cold chain infrastructure as well as rural infrastructure needed to reach national corridors, while at the same time ensuring the reliability of service needed to maintain Canada’s reputation as a reliable supplier of agriculture products.”

Whether infrastructure investments go to projects in regions where farmers and agribusinesses can make use of them is not guaranteed.

Ugurhan Berkok, an economist specializing in the defence sector and associate professor at the Royal Military College of Canada, says intelligence capacity and capability will be particularly important as Canada, being an Arctic nation and critical intelligence ally for the United States, seeks to improve capability in the north.

Modernizing the North American Aerospace Defense Command, for example, will require additional manpower, investments in facilities, as well as roads and other infrastructure to keep facilities in operation. Such infrastructure will likely have little to no effect on the agriculture sector given how far north they are.

But similar investments in east-west infrastructure might be a different story.

Unforeseen effects

“We are 10 countries plus three territories. Troop movements will require further infrastructure,” says Berkok, referring to the need for rapid force deployment capability across Canada (and referring to provinces as countries as Canada is a country with significant differences between regions).

Berkok says that a rule of thumb in military operations — that one deployed person requires three behind-the-scenes support individuals to operate effectively — highlights how investments in specific parts of Canada’s defence capacity necessitate additional investments downstream. The effects of both types of defence spending could have unforeseen positive effects for farmers and agribusiness, even if that spending occurs in remote areas.

But again, what exactly those investments will be is not yet known.

And the line between direct military and defence-adjacent spending is still blurry.

Berkok says doubling the number of F-35 jets, for example, requires the construction of specialized hangars to house aircraft. While the Prime Minister’s Office lists airport spending as defence-adjacent, construction of hangars capable of housing jets at airports is likely considered direct military spending. The 1.5 per cent defence-adjacent commitment is “a black box at the moment,” says Berkok.

For now, Berkok says he is watching what Canada’s European allies do. What they decide falls into defence-adjacent spending is likely to inform Canada’s approach.

Fertilizer, food and telecommunications

Al Mussel, agricultural economist, research lead for the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute and founder of Agri-Food Economic Systems, agrees that investments in Arctic infrastructure will likely have “minimal implications for agriculture.”

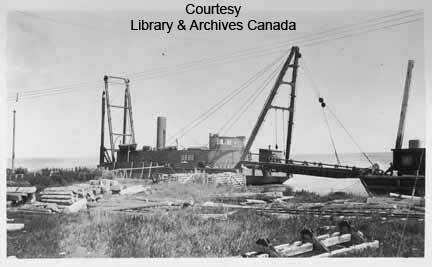

If, however, the government’s strategy involves developing the Port of Churchill or another salt-water port on Hudson Bay, agricultural commodities, such as grains and fertilizer, would benefit from another export location — and one more conveniently located for the delivery of critical food and mineral products to many allies and trading partners. This very thing was attempted in Nelson, Man., during World War One, although the project was abandoned in 1917.

One of the challenges with developing ports at Churchill, and elsewhere in the wider region, is overcoming transportation issues across northern muskeg and longer periods of thaw. Mussel says transport issues are what have scuttled development plans in the past.

As reported by the Manitoba Co-operator in March 2024, the port’s recent history “has been messy, with the sole rail line linking Churchill with the rest of the province plagued by service disruptions.” In 2018 the port’s American owner, Omnitrax, sold the port and rail line because it could not manage the cost of rail repairs. Better environmental conditions, lower insurance cost and a higher car cycle also make southern ports more attractive for grain companies.

There is still some interest in a northern port, however, with the premiers of Saskatchewan and Manitoba signing a memorandum this July to improve access to Churchill for the purposes of exporting prairie commodities.

Port difficulties aside, Mussel believes the strategic value of food and fertilizer export capacity should not be underrated. He cites both World Wars, when the United Kingdom was sustained largely by Canadian and American food exports, as historical lessons that appear to be “conveniently forgotten” today.

A similar point is made for fertilizer and mineral resources. During World War One, the British Empire and its allies had access to fertilizer-rich regions of the world, enabling the production of both food and explosive munitions.

Germany, on the other hand, had to rely on the production of synthetic fertilizer through the Haber-Bosch process. This proved to be a debilitating problem for the Central Powers as the war went on because fertilizer production was increasingly diverted to the development of munitions, including explosives and poison gas.

While Canada is a global supplier of potash, Mussel says it’s possible other vulnerabilities could be addressed if mineral exploitation is considered defence-adjacent spending. To that end, Ontario and other provincial governments have identified mining projects as top economic priorities.

“We know in terms of making monoammonium phosphate, diammonium phosphate or triple superphosphate, there’s nothing in Canada. It’s a major source of vulnerability for us,” says Mussel, citing ongoing pushes for mining in Ontario’s Ring of Fire, a region with promising mineral development opportunities, which could secure domestic supplies of fertilizer as well as some of the materials required for semiconductors and other important products.

“I would hope that part of the Ontario proposal around the Ring of Fire would maybe create some potential for phosphorus and therefore phosphate fertilizer manufacturing.”

Chris Sands, director of the Hopkins Center for Canadian Studies at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, points to the strategic value of combining Arctic port expansion with mineral extraction.

In a Substack article published just prior to NATO members announcing their commitment to spending five per cent of gross domestic product on defence, Sands argues, “Ports on Hudson Bay and the Arctic islands offer access to the north and world markets. Churchill, Man., hosts a deepwater port, an airport, and a rail line to the south and all need new investment. A new port close to Ontario’s critical-mineral rich Ring of Fire region could be a more practical route for bringing minerals to world markets than road or rail.”

And both Berkok and Mussel point to a long-standing issue across rural Canada — access to high-speed broadband — as another area where infrastructure investments for strategic purposes could bring clear dual-use benefits.

From a military perspective, Berkok says artificial intelligence and developments in advanced monitoring systems at military installations — systems built to rapidly “compute signals from beyond the horizon” — will require large servers with significant energy requirements.

Broadband communications more generally will continue to be a critical and growing requirement wherever the government decides to invest in defence installations.

Civilians living in areas long neglected by telecommunications providers, including the far north and rural parts of the country, might inadvertently find it easier to access broadband services as providers prioritize specific networks.

Canada’s powerhouse

The $150 billion invested into defence annually is no small number. Coincidentally, it’s also the amount agriculture contributes to the Canadian economy every year.

For Keith Currie, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, the new NATO targets offer another opportunity to leverage agriculture for economic security against threats from maligned actors.

Historically, however, there has been a lack of recognition of how much agriculture contributes to the country’s gross domestic product — approximately seven per cent — and the potential to grow that revenue through strategic investments from the federal government.

Forestry, steel and aluminum manufacturing and the automotive sector garner a lot of attention, Currie says, yet combined do not contribute as much to the national purse nor employ nearly as many people as agriculture. He encourages policymakers to “dust off” the Barton Report (a comprehensive set of recommendations for economic investment from the federal government’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth released in 2017) which identified the agriculture and agri-food sector as a strategic area with “a strong endowment and untapped and significant growth potential.”

Currie lists several gains, including resolving general structural dysfunction at the Port of Vancouver, enabling a method of access to port infrastructure at Prince Rupert, improving storage capacity in Thunder Bay and Churchill, investing in electrical and natural gas infrastructure in farming communities, as well as rural broadband.

“Infrastructure like hydro lines are 90 years old. Farms are requiring much more power now, but most farms don’t have three-phase power,” Currie says.

And moving the Pest Management Regulatory Agency and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency into Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, rather than keeping them under separate ministries, is another potential move which could further enable agricultural developments.

“If the federal government looks at that, can we get bureaucracy to be more tuned in — not going out after regulations have been put in place saying, ‘Here’s what we did, what do you think?’ How do we make it better before putting it into policy?” asks Currie.

“Agriculture is the number one industry to be investing in in this country, and that hasn’t changed. There can be a lot done without a lot of money or in combination with different programs.”