Plant breeding is as old as agriculture.

It might have been instinct that led hunter-gatherers to collect a handful of seeds and sow them into prepared soil or perhaps it was accidental opportunity. Either way, human’s history of cultivating plants to develop beneficial characteristics evolved slowly into the domestic crops we know today.

Figs are the oldest known domesticated plant dating back 11,400 years in the lower Jordan Valley, West Bank. A thousand years later, founder plants native to southwest Asia, such as emmer wheat, einkhorn wheat and barley, were domesticated. Pulses such as lentil, pea and chickpea were domesticated for their oil. Maize was domesticated 9,000 years ago in southern Mexico. Today, the category of founder plants includes nearly 20 other species of cereals and legumes.

Read Also

Farm & Family – March 6 edition

Can a farmer also be a conservationist? The short answer is “yes.” But it’s a balancing act and an on-going…

Although the first farmers probably didn’t know they were breeding plants, the ones that thrived survived.

Fast-forward 10,000 years and we’re still at it. Plant breeding is now a tad more sophisticated and with a warming planet, the challenge becomes breeding plants that are climate-resilient.

Modern challenges in warming world

Researchers at the University of Hawaii (UH) have pioneered a new way to breed climate-resilient crops faster by combining plant gene-bank data with DNA and climate analysis. Their research focuses on sorghum and the method they’ve developed could speed up ways to secure future food supplies worldwide.

“Plant breeding is defined as the selection of plants for human benefit,” says Michael Kantar, associate professor in the UH Mānoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resilience.

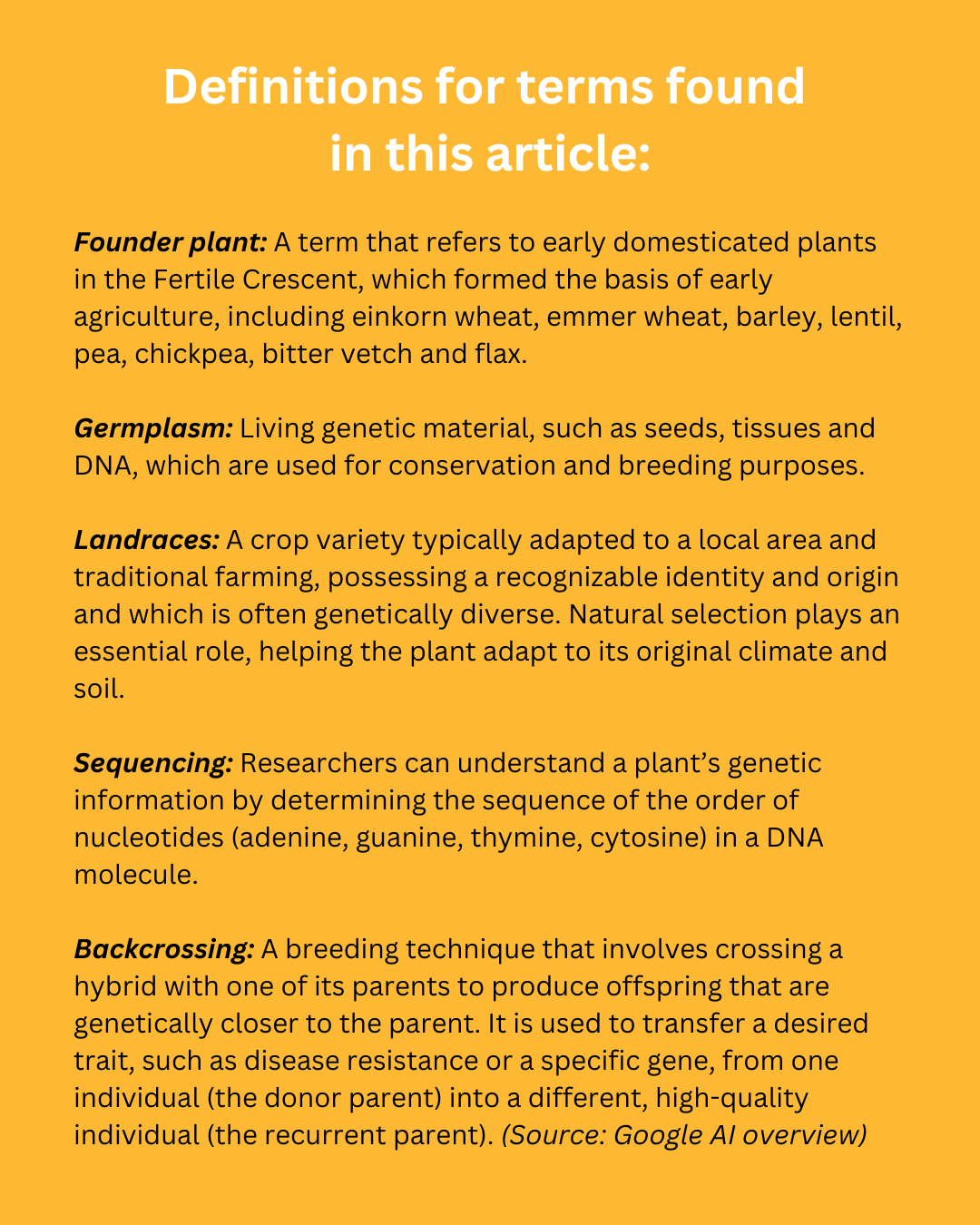

“Every plant breeding program relies on diversity to find new things that people want. Historically, this has been food, fibre, feed and medicine. Germplasm collections have been around for thousands of years informally. While some traits have been well characterized in (gene-bank) collections, climate resilience has not been. This is largely because measuring drought, heat or waterlogging stress is very hard and expensive.”

The research, published in Nature Climate Change, identified the best potential plant parents and geographical areas that support the most promising genotypes for crop improvements.

Plant gene-banks are repositories of millions of diverse seeds, plants and other genetic material collected from around the world. They serve as insurance against natural or human-induced catastrophes that could decimate global food, and they are vital resources for plant breeders developing new crop varieties with a range of traits from drought resistance to disease tolerance.

“These collections are absolutely amazing,” says Kantar. “They are living libraries but often they are more like museums. We really wanted to make use of the library part. We wanted to try and find some way to see if we could develop a smaller set of individuals to use for crossing to make experiments easier.”

The innovation: environmental genomic selection

The research team used 1,937 unique samples, or accessions (unique samples of seeds representing a breeding line or a distinct population) of sorghum valued for its heat and drought tolerance to test a new method called environmental genomic selection. The method combined DNA data with climate information to predict which plants would be best suited to future warmer conditions.

“What environmental genomic selection does is, instead of predicting the value of an individual plant for a specific trait like yield, we predict its response to environmental conditions,” says Kantar. “Genomic selection takes thousands of small differences in DNA across the population, and we calculate the effects of each change with respect to an environmental variable like heat. We get a ranked list of what plant will survive under hot temperatures.”

As an example, Kantar says that a change from an A (adenine) to a T (thymine) on chromosome 3 may result in the ability for the plant to tolerate temperatures that are 0.0001 degrees higher than the average temperature the crop lives in.

“We do this same calculation thousands of times and eventually end up with a score that says Plant A will be able to survive in temperatures 5.6 degrees higher, so this now becomes a candidate to be used as a parent in a breeding program.”

The system can be applied to any crop with the right data, not only sorghum but others such as barley, cannabis and pepper to name a few. Instead of testing thousands of plants in a field, scientists use a smaller, diverse mini-core group to forecast crop performance in different climate environments to help breeders more quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

“Germplasm collections are really big, often tens of thousands of accessions,” Kantar says. “This has led to many folks creating different ways to subset the accessions to try to find traits useful to humans. Most of these methods focused on different types of sampling genetic, geographic, use or phenotypes. Each way of sampling has pros and cons. Starting in the late 1980s, it became popular to create core collections, subsets of collections based on maximizing genetic diversity.”

Kantar says that a threshold of diversity was set, usually based on a metric like allelic richness. Alleles are variant forms of a particular gene and over time the combined inherited differences are the basis for genetic diversity. A researcher would find the minimum number of individual plants that had 80 per cent of total diversity. But those core collections were still very large, often thousands of individual plants.

“In the 21st century, a lot of effort was placed on creating smaller (easy to control) collections — mini-cores — in which individual researchers could grow usually less than 500 accessions,” Kantar says. “These mini-cores represent a huge amount of genetic diversity of important crops but in a small enough package that an individual researcher could grow and evaluate all of them at once.”

Predicting performance for the year 2100

Clarifying critical climate information means projecting what the temperature will be in the region where farmers want to grow a specific plant. For example, Kantar says that if a plant is currently thriving in a place where the average temperature during the growing season is 24 C but by 2100 is expected to be 27 C, then it is important to source a plant accession that will be able to grow under that 3-degree change. The genomic selection method predicts which plants will grow well under these kinds of temperature changes.

“For the environmental genomic selection specifically, and genome environment association in general, you need certain types of data,” says Kantar. “You need to have the latitude and longitude of where plants were collected from. You need to have genome-wide markers, which can be from a wide range of technologies, the most common now being sequencing. And the plants need to be either wild relatives of crops or landraces.”

The value of the team’s work lies in the speed and efficiency of developing a new genetic order for crops to meet climate challenges. Kantar has been talking with crop breeders about options for not only meeting climate challenges but also resistance to diseases that may develop because of a warming world.

“Breeding is a complex decision problem,” says Kantar. “People want a lot of things. There has been a lot of work on trying to deal with these sometimes-contradictory goals. In this case we use this method to try and find both quantitative and qualitative variations. This allows breeders to do both population improvement and backcrossing. A major goal is to get breeders a small set of lines that they are confident will have the traits they need so they will put them into their breeding program.”

The researchers discovered that nations with high sorghum use will likely need genetic resources from other countries to effectively adapt to climate change.

A global effort for future food security

“There are national and international (germplasm) collections,” says Kantar. “Some countries have all the variation they need within these national programs or they can collect it from local farmers. They may have easier access due to not having phytosanitary (plant health) regulations to move plant material. Other countries will need to get germplasm from international collections. In some cases, this means a delay in being able to breed.”

The environmental genomic selection approach saves time. And, by using the diverse mini-core approach to forecast how crops will perform in different environments, breeders will be able to quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

The method could be expanded to a variety of crops and used to support future breeding.