For over a decade, farmers have been told that a systems approach will bring greater efficiency to their farms. Quality assurance, nutrient management plans, environmental farm plans, big data, precision ag — they’ll all help increase efficiency and might even improve profitability.

In the past six months, a new phrase has exploded into the business world: blockchain technology.

The phrase has become nearly impossible to avoid, and the volume of articles, news reports and advertisements that refer to this global movement can be overwhelming.

Most people became aware of blockchain through another phenomenon that swept into the public consciousness a couple of years ago, and not always in a good way, i.e. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

Read Also

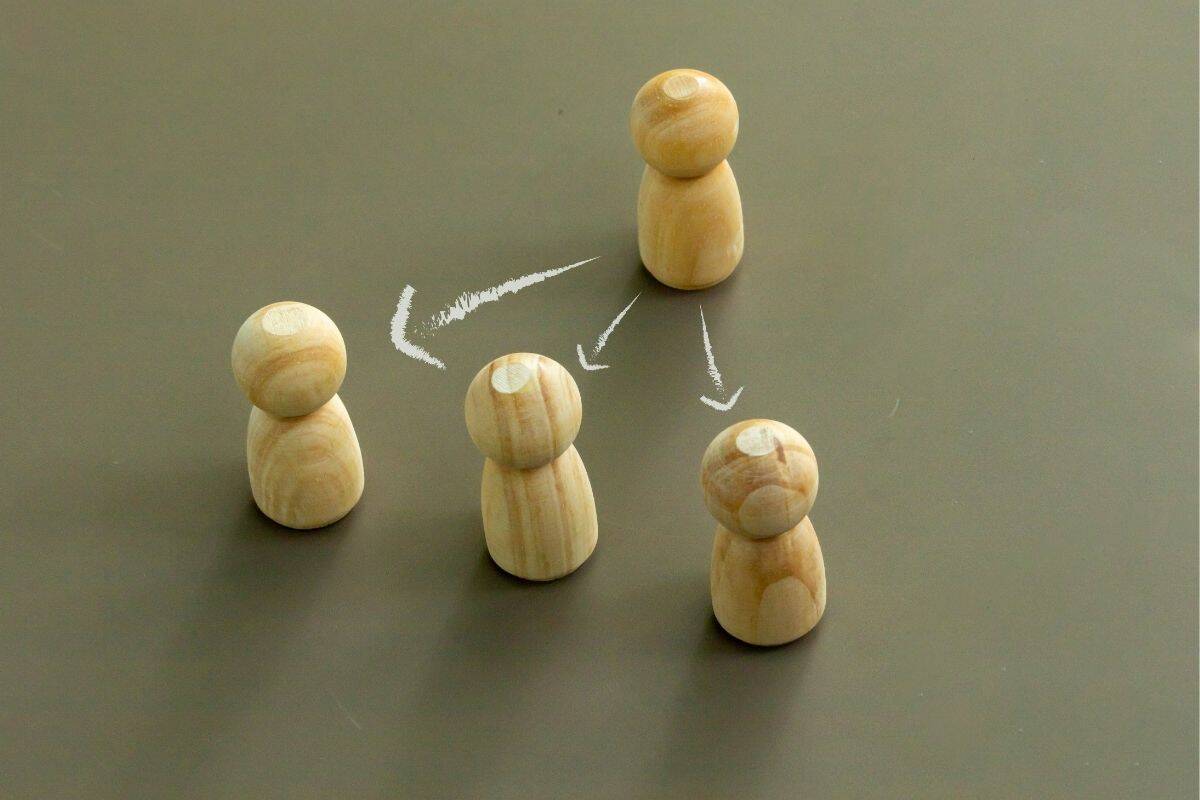

Executive decisions: what and when to delegate on the farm

Consider the end state you’re working to achieve on your farm when deciding what tasks to delegate, when to do so and on whom, farm management advisors recommend.

But its applicability in the food value chain is what makes blockchain enticing for those in the agricultural sector.

What’s a blockchain?

Everyone involved in the current blockchain frenzy has a definition for the term, but keep in mind that there are dozens if not hundreds of companies and interests already incorporating the technology into their management systems.

A typical definition came in an article from June 2018, McKinsey & Company, a U.S.-based management consulting firm, defining blockchain as “a distributed ledger or database, shared across a public or private computing network. Each computer node in the network holds a copy of the ledger, so there is no single point of failure. Every piece of information is mathematically encrypted and added as a new block to the chain of historical records.”

More helpful may be to look on a blockchain as a system that can take data from sensors and then use algorithms to generate information streams that deliver greater value to all participants in a blockchain relationship. The sensors and algorithms can describe a crop, a bird or animal for slaughter, even a piece of equipment like a tractor or sprayer.

On its own, this will not make growers more money. But it has the potential to be used to help with digitization, automation and tracking of information, and to improve efficiencies by identifying parameters that could drive a farmer’s bottom line.

Although in their infancy, blockchains may be the basis for altering business processes, creating more secure information channels and helping agriculture build stronger ties with consumers and value-chain participants.

Grain sales

Blockchain technology could drastically alter the way grains and oilseeds are sold, bypassing brokers and local elevators. Or it might create a line-of-sight protocol for livestock producers, providing them with a means of garnering a premium for carcass quality.

One thing is certain, as much as individual farmers, stakeholders or end-users might be taking their time and studying their options, others have already taken steps into the global picture. The Chinese government, Wal-Mart, IBM (touted as the leader in the field) and an amalgam of food companies including Dole, Kroger, McCormick & Company, Nestlé, Tyson Foods and Unilever are already working on food tracking systems using blockchain.

It’s important to understand the could and might in all of this, because the technology carries so many questions.

Most participants agree that agriculture — and most of the rest of the business world — is still three to five years away from seeing full-scale implementation. Add to that the fact that growers and producers have been told about the many wonders of previous technologies that have yet to realize their full value or return on investment, and that could slow its rate of acceptance further.

A huge hurdle

The biggest challenge for blockchain technology in the agri-food industry may be the number of sectors encompassed within it. Horticulture, viticulture, dairy, livestock and poultry production, grains and oilseeds, aquaculture… All have their possibilities, but also their unique complications, including transportation and logistics, storage and processing.

It all means there’s a huge potential for blockchain, but also a high cost of entry.

Specialty cropping ventures such as identity preservation (IP) soybeans or other pulses grown under contract may be among the first to justify a blockchain system.

Doug Miller is the managing director of certification technology services with the Canadian Seed Growers Association and is focusing on blockchain applications as part of his masters in business administration. He has also studied blockchain technology through a six-week certification at Oxford University.

Miller is learning to separate fact from fiction while garnering a better understanding of blockchain’s potential. A warning he’s heard time and again in his training is that “a man with a hammer thinks everything is a nail.” In other words, not everything is ripe for a blockchain process.

“There’s a set of questions you can work through to determine whether your business application will fit with blockchain,” says Miller, adding it’s important to think of blockchain in scale. “This is a technology that’s relatively new, and one comparison that’s easy to make is with the internet.”

As big as the Internet

Whether the current media attention can live up to the hype, Miller suggests taking any article on blockchain and replacing the word with “internet.” In the mid- to late-1990s, the internet was hailed as the greatest innovation, even as others said its potential was limited due to bandwidth issues, access and availability. Those few limitations had many doubting its real value.

“With blockchain, that’s where we’re currently at — it’s less than 10 years old, it’s a technology that’s maturing very quickly and as problems come up, they’re being addressed,” says Miller. “Can it live up to the hype? It’s a little too early to tell, but all signs are pointing to the direction where this can be a disruptive technology but also a new fundamental technology.”

Among its many attributes, Miller cites blockchain as a technology that can — and will — help the food value chain by reducing costs or increasing revenues. In certain sectors, it has the capacity to reduce or eliminate the need for intermediaries like brokers or wholesalers. In the case of cash cropping ventures, it could be possible for sensors to measure quality parameters of grain as it’s being harvested. Transactions between farmer and end-user could then be carried out via pre-set contracts.

That technology exists already: a company called Bext360 based in Colorado has built a device that uses an optical sorter, artificial intelligence and machine learning to sort and grade coffee beans. The beans are fed into a sorter where the quality of each bean is assessed and provides an aggregate of all the quality standards that are pre-set, affecting the price the buyer is willing to pay.

“Think of how that could be applied at the elevators,” poses Miller. “The farmer can dump the grain at the elevator, it passes through and the algorithm indicates ‘this’ can be the price based on ‘these’ parameters. Then a buyer accepts or denies and the farmer might be paid instantaneously for delivering that product.”

Miller started his career at the same time as the Triffid flax incident in 2010 and says blockchain could prevent unapproved trade between a grower, an exporter and an overseas customer. If a soybean variety bears a trait that’s approved in Canada or the U.S. but not in the E.U., a contract on the blockchain could negate a sale of the soybeans to non-approved country — all in a matter of seconds.

Consumer transparency

In a broader scope, blockchain could help the agri-food sector with the positive move away from traceability to transparency. That would fit with a presentation Miller made that dealt with “the rise of the information-hungry consumer,” enabling participants to see everything that’s happened to a product throughout the chain. More consumers want to know everything about the food they’re eating: they want the story and the specifics.

“What we can do with blockchain is that we can tell that story and that’s going to be really interesting for agriculture, because we’ve had a problem with telling our story to date,” says Miller. “But just looking at my application, for my producers, I look at blockchain and I can start to tell a story based on the data points that I already have that can make your product a lot more valuable.”

On the other hand, it’s not something that has translated to the customer’s plate just yet. In theory, though, it allows for the shift in mind-set that turns the consumer’s perception that farming is all red barns and hand-feeding chickens, and creates a new, more relevant picture of modern-day farming, framed in a positive manner with transparency.

Speed and accuracy

In an article written by Aidan Connolly, chief innovation officer with Alltech, blockchain’s potential is clear and obvious by the list of companies and interests involved in developing their own value chains using the technology. In one case, a supply chain trial was conducted between Wal-Mart and IBM in which a food product was traced through each level, back to its point of origin. It took 2.2 seconds. Contrast that with food recalls of the past which often took days, if not weeks, to determine where or how part of the system failed.

“In the case of blockchain, the process becomes faster and more transparent, and it’s easier to see what variations have occurred in the manufacture of something where there are multiple people involved,” says Connolly. “It does not, of course, prevent fraud from occurring but it does make it easier to spot where that fraud has occurred and if an investigation or recall is required.”

Connolly believes there’s a benefit to trading traceability and transparency for the potential of capturing more of the customer’s confidence, with the ultimate goal of encouraging more loyalty leading to profitability. In the past, the danger has been that such systems have been embraced yet farmers find themselves bound by onerous paperwork and record-keeping without any apparent benefit to themselves.

“A lot of it comes down to who embraces the technology, how it’s embraced and how it’s sold to the consumer, be it a food retailer or the end-consumer,” Connolly adds. “Otherwise, undoubtedly, it’s another exercise in dumping more work on to the farmer’s plate. If done the right way, it can solve some of the larger issues we have at play in agriculture.”

Questions, questions

That’s one of many hurdles that blockchain has to overcome in order to convince some participants of its worth. There’s little doubt, reading through the many articles and editorials on the subject, that blockchain technology is an incredibly powerful system. But it also comes with as many questions about procedure and specifics as it does claims and accolades. Dr. Karen Hand, director of research data strategy with the University of Guelph’s Food from Thought program, suggests there are far too many uncertainties involved with blockchain — in its current form — to make sweeping recommendations about participating. Not only is it immature, there are also different types of blockchain, be it private or public, permissioned or non-permissioned.

“If we were to look at where it would be best served, it’s in an environment that is private and permissioned, so that it’s very tightly controlled as to who the partners are,” says Hand. “Just implementing a blockchain for the sake of blockchain isn’t an intelligent strategic move. It has to be like any technology where you consider what’s already working, look at the blockchain and see if it would improve efficiencies.”

There’s also the issue of “use-cases,” and those need to be defined where there’s a specific requirement where blockchain would enable greater efficiency. Like Miller’s observation about a man with a hammer seeing everything as a nail, Hand contends it’s not a matter of “here’s blockchain, let’s find ways to use it.” Instead it’s finding the fit for blockchain by finding efficiencies for a particular operation.

For Hand, it always comes back to the use-case scenario. In a use-case, it’s good if there’s an opportunity for food safety and traceability for the consumer, and the record is immutable and the ledger can’t be changed. The problem is, there may be trusted partners who do all of that already. But complications arise if the blockchain is using an immutable ledger yet the product itself can be tampered with. How can that be tracked and measured?

Hand asks these and other questions because the answers aren’t readily available right now and the system itself is immature enough that many of those questions have yet to be asked. Yet she believes those questions need answers and rules need to be built into the blockchain. There needs to be trust, the right partners and the right use-case to provide proof that it’s doing what it has set out to do. In food safety, there’s a need to prove that food hasn’t been tampered with, although it is possible to trace ownership of a product, but how can someone prove that nobody touched it?

Another component of blockchain that lacks that maturity is differentiating between data-based knowledge and contextual knowledge. It’s one thing to spray a field and have a sensor indicate that “x” pounds of an active ingredient have been applied — that’s the data-based knowledge. But it’s that conceptual knowledge that doesn’t recognize a change in wind speed that results in one row receiving more chemical than another row. In its current form, blockchain can’t differentiate between the data-based facts and the conceptual nuances that can arise in day-to-day management of the farm.

“We have to know how is it measurably better,” says Hand. “How do you measure that and what is the cost of each transaction? If it’s not correct, it could end up costing more, and we don’t know how much it would cost to have a fully implemented blockchain system. I don’t think those are answers that we have yet and we need people to explore them and to look at them and do these actual return-on-investment type of analyses.”

What’s next?

It may also be possible, says Miller, for growers to order and pay for worn parts on a piece of machinery as it’s rolling through a field. With an array of sensors — some of which may already be in place — blockchain can detect the breakdown or worn-out nature of a part, place the order for that part, and pay for it in a matter of seconds. How much would such a system be worth in terms of minimizing downtime at planting, during spraying or at harvest?

Blockchain and its underlying algorithms and protocols allow for trust in what can become a trustless system. It’s an interesting turn of phrase — “trust from trustless.” In 2016, an engineer named Henry Berg wrote that “blockchain is trustless because the system was designed so that nobody has to trust anybody in order for the system to function.” As negative and counterintuitive as that sounds, it’s actually a positive attribute of the technology.

In the late 1990s, many industry stakeholders characterized the rush to develop biotech systems as if researchers and breeders were boarding a train. “Better get on board before the train leaves the station!” — was an oft-cited piece of advice. Asked whether there’s a similar deadline on blockchain, most people see that three- to five-year window as the more reasonable time frame.

“I’m not sure we’re at the point where you have to get on board the blockchain train,” says Connolly. “Of course, if you’re a supplier to an organization like Wal-Mart or other food retailers and they insist on it, then clearly this will become a cost of doing business. I don’t think it’s a good idea to be the last on it, either, but I’d suspect that most people will be forced to come off the fence and take a position on blockchain in that three- to five-year period.”

Above all, Miller believes, blockchain participation requires moving to a paperless business model. Only through digitizing information and operations can this work to its optimum.

“People need to get into position where things are being put into databases, where data are being captured and we’re not relying on files,” he says. “We need to be pushing that way quickly so we can ride the waves of these technologies as they come out.”

More info