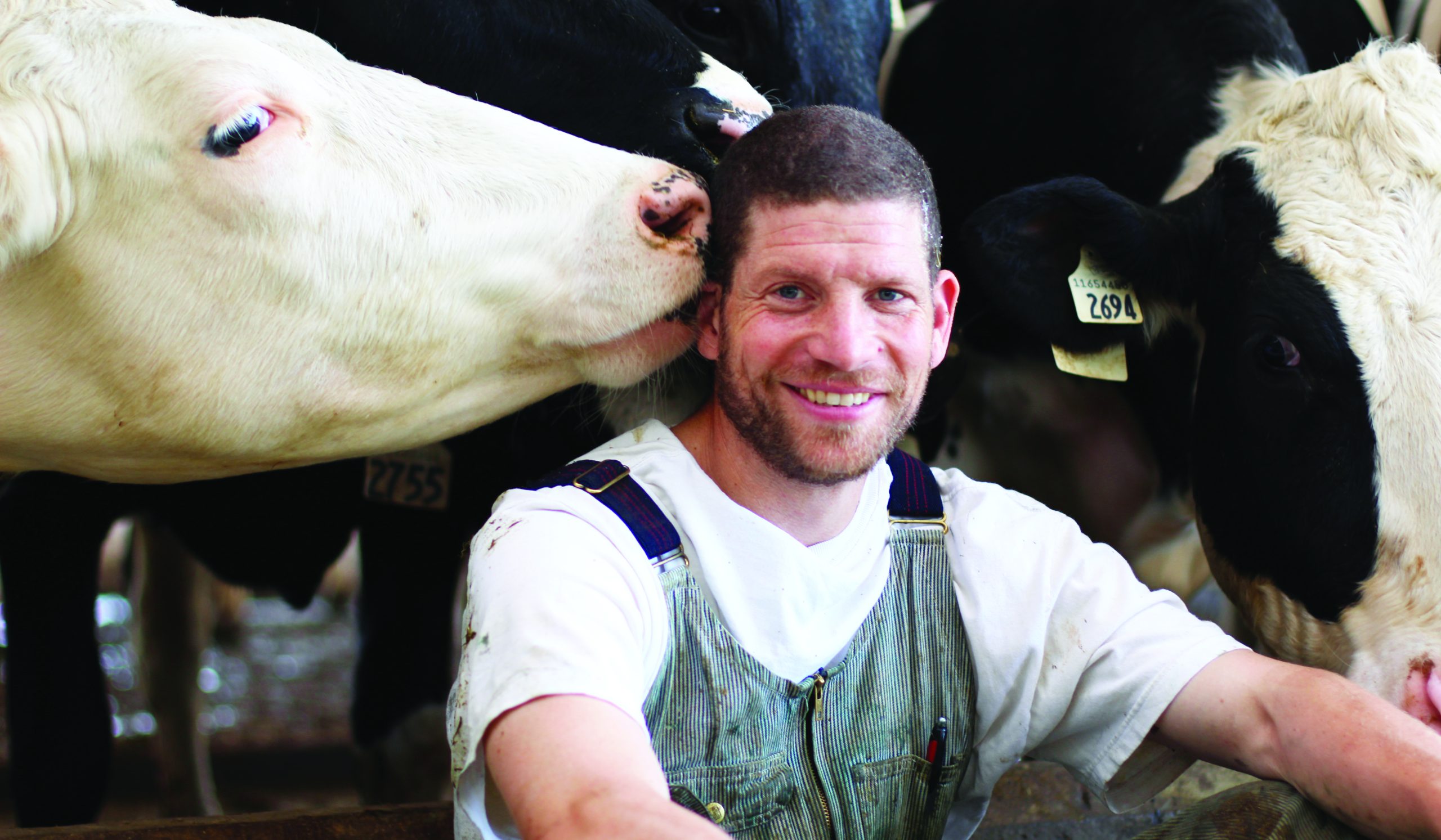

Loewith and Sons Limited has kept to the same business model since 1948: Raise cows, milk cows, then sell the milk to the wholesale market. After all, it’s a model that has proved itself across the years and it has powered the Hamilton, Ont. dairy farm through multiple expansions and continued increases in production.

“We’re production-oriented,” the unapologetic third-generation Ben Loewith says. “Our first focus has always been to expand the dairy operation. It’s a skill set we have, something we’re good at and it’s very simple to add on to a facility and do more of what you’re already doing.”

Now, though, the farm is at its limit with 500 cows. Continued expansion has proven impossible: Land around the farm is scarce, quota is a limited resource and markets are stagnant, forcing Ben, who farms with his dad, Carl, and his uncle, Dave, to evaluate new growth strategies.

Read Also

It doesn’t have to be the end for your farm

Options for farmers without successors to pass on the farm.

“We don’t see the milk business growing,” says Dave. “Looking down the road, it’s not possible to make big expansions in the milk side of things.” “The revenue side of things started to slow down, if not stagnate a little,” agrees Ben. “We weren’t seeing the year-over-year growth that we like to see.”

Their solution? Diversify.

Get the timing right

The Loewiths started talking about processing and bottling milk around 2020. Data on farm diversification is scarce but international statistics show they aren’t alone. In almost every developed country, the proportion of farmers with diversified operations is on the rise.

They were also persuaded that onsite sales would be popular because of a combination of local factors. These included heavier volumes of traffic travelling the farm road, regular drop-ins from visitors requesting tours and increased demand for local foods.

Their hope is that diversification into direct-to-consumer sales will be effective for expanding the farm — and reviewing the spreadsheets also convinced the Loewiths that the timing was right to add some new revenue streams to their portfolio. “We started looking at other opportunities,” Ben says. “We really strongly believe that our top line has to continue to grow,” Ben says.

In the West

Meanwhile, the addition of value-added products helped fuel continued growth at Twin Oak Farms in Lougheed, Alta.

Fifth-generation farmer Dan Skoberg grows grain and raises cattle and hogs. During the pandemic, Skoberg and his wife, Shelly, started making bacon.

“We started playing around with recipes and giving (bacon) to our friends and families and they wanted more,” Dan says. “We made 50 pounds and sold out right away.”

The COVID-19 pandemic led to supply chain issues and fueled the “buy local” movement, making it the ideal time for Twin Oak Farms to introduce a new, local product.

In 2021, the Skobergs built a “bacon barn” on the farm and began producing seven flavours of cured bacon that is sold to restaurants, supermarkets and distributors across Alberta. The inspected facility produces between 300 and 1,000 pounds of bacon per week.

“Everybody is looking for a way to diversify and bring more income into the farm,” says Shelly.

Prioritize partnerships

The Skobergs started making bacon from the hogs raised on their farm but chose to purchase hogs from local farms to make their artisan bacon instead of scaling up their operations. Partnering made sense from a financial and logistical perspective.

“Hogs are a tough, grueling industry and I’d like to support the guys that are doing it rather than get into it myself,” Dan says. “A big part of our model is supporting local businesses.”

The right partnership was also essential for helping Lindsey Good find niche markets for the field peas he grows at Stirlingville Farms just north of Calgary at Carstairs.

Until 2019, the pulses were grown as a rotational crop and sold into the wholesale market but Good, a fourth-generation farmer, knew that pulses, plant-based diets and local goods were more popular than ever and he wanted to capitalize on the trends to move up the value chain.

Good started looking for ways to connect with entrepreneurs who had solid ideas for value-added products but needed pulses (and a partner) to bring their ideas to market. A contact at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology introduced Good to Faaiza Ramji, an entrepreneur working on pea-based foods. It proved a perfect match.

After a lot of research and trial and error, the pair established Field Notes, the first business in North America to turn field peas into distilled spirits. Their first product is Don’t Call Me Sweet Pea, an amaro (or Italian herbal liqueur) made with peas from Stirlingville Farms and other ingredients grown in the West. Good understood that making and marketing a value-added product required a different skill set than farming and he needed the right partner to bring the knowledge, labour and capital required to execute on an idea.

“You’re looking at a completely different business,” he says. “Unless you have a person within your farm organization who has the skill and the time and energy to spearhead the project, you need a partner to make it work.”

Expect plans to change

Farmers often experience a lot of twists and turns on the path to diversification.

When Good met Ramji, she was working on a pea-based snack food that she hoped to export to India, not a distilled spirit that would be marketed in Canada. It took research and a few missteps to land on the right product and create the strategies to execute on it.

“We’re not going to successfully compete against a multinational distiller,” Good says. “It’s about understanding the nuances of the value chain for our product and accessing those channels rather than thinking we’re going to be selling cases to every liquor store in Canada.”

Diversification also requires patience — and that was one of the hardest things for Dan and Shelly Skoberg when they decided to start producing bacon for retail sales.

“It was a lot of research and a lot of things we’re not used to,” Dan Skoberg says. “We’re moving into a market that we’ve never been in before so there was a big learning curve.” In addition to the time it took to develop recipes, source pork, build a processing facility and meet all of the labelling requirements, it’s also taking time for the Skobergs to see a return on investment.

“Any money we made last year went right back into the business to buy containers, ingredients and freezers and that was hard,” says Shelly. “We knew we were making money but … we needed patience to see the account grow to see we were making money and doing the right thing.”

The “right thing” has changed several times for the Loewiths. The family originally planned to install a vending machine in the milk house where customers could use a credit card to purchase fresh milk but, as the idea took shape, the concept expanded.

First, the plans were amended to include a small retail store but the idea went through several more iterations before the partners settled on building a 10,000-square-foot retail store that will sell fluid milk, cheese curds and yogurt, all made with milk from the farm’s herd of 500 Holsteins.

It took 19 months to get the building permits, which were approved in June 2022. The costs for labour and materials skyrocketed during that time and the ever-increasing cost of construction led to several meetings about whether to move forward; the family remained committed and the new store, Summit Station Dairy and Creamery, is expected to open in 2023.

As construction for the creamery gets underway, the Loewiths have laid the groundwork for an additional diversified element. They applied for (and received) a grant to install 490 kilowatts of solar power on the farm — enough energy to run the farm. The project, which the family started discussing more than a decade ago, is also expected to be online next year.

Dave Loewith acknowledges that the farm is making big investments in diversification but he believes the farm is in the right place to make the strategic moves.

“Even though it’s a big commitment, we’re not risking the flagship (farm) on this,” he says. “It’s a nice to-do, not a must-do.”