Over the years, all the major machinery brands have shown autonomous concept tractors to the public at farm machinery shows. They clearly wanted to get the message out that they have the engineering ability to build them. For example, CaseIH displayed its concept autonomous Magnum tractor at the U.S. Farm Progress show in 2016 where sister brand New Holland introduced the public to its similar autonomous T7 tractor. For its part, John Deere had shown a robotic utility tractor several years prior to that, and at the 2019 Agritechnica, the green brand showed an autonomous, tracked, electric concept machine.

But all have been reluctant to launch in the marketplace. In North America some brand executives said fear of U.S. liability laws, which could see them paying millions to settle law suits should an accident occur, was a prime consideration.

As farmers awaited market-ready autonomous tractors that didn’t materialize, a few industrious individuals began tinkering with the concept and built their own. But no one in Canada expected the first commercially available autonomous machine suitable for broad-acre farming would come from SeedMaster, a small manufacturer that had never produced a motorized vehicle in its entire history. But that was the case.

In 2019, SeedMaster’s Dot autonomous implement carriers (or power platforms as they’re now named) started work in paying customers’ fields for the first time. A handful of these machines were sold to farmers in Saskatchewan, all within driving distance of the SeedMaster manufacturing plant in Regina. That distance limitation was to ensure that as the company began commercialization of these units, they stayed near where they were built so its engineers could work with the new owners to iron out any unexpected problems.

Read Also

Sibling squeeze part 6: The emotional stakes of a family legacy

The final instalment in a six-part series exploring the challenges of sibling conflict and the effect it can have on…

The autonomous machine started as a hobby project of SeedMaster’s president and founder, Norbert Beaujot, but it evolved into a production offering for the company.

However, in late 2019 Dot Technology Corp. (the subsidiary company formed by SeedMaster to focus on Dot autonomous technology) was sold to SeedMaster’s technology partner Raven Industries, which decided to merge it into the company’s stable of concept autonomous ventures. That changed the market trajectory of Dot, with Raven deciding to pause the commercialization effort temporarily as it undertook further R&D.

“When Raven purchased the remaining 40 per cent we pulled back (from retail) to expand the R&D,” says Chris Morson, the company’s sales specialist. “We’ve been working on the path planning part of Dot and the implements and connectivity also.

“There are four customers who have purchased a Dot. And we have seven units in Saskatchewan that are in a validation program. They’ve been put to work in farm fields, just as if a customer had purchased them, the one difference being that we’re manning them. So one of our employees is doing the programming with them and getting them going every day.

“We’ll be expanding the validation program through the start of next season. It’s a bit fluid right now, but I think there’ll be another four or five machines added to the validation program for next year, some of them in the U.S. and abroad.”

Despite the success of the validation program so far, no firm date has yet been announced for the resumption of retail sales. “The date is a bit fluid too and I don’t want to put a timeline on it,” says Morson.

Dot consists of a U-shaped chassis powered by a 6.7-litre Cummins diesel engine with a hydrostatic drive system. It operates autonomously on a preprogrammed course, and it can be manually operated with a remote control console if necessary. It is designed to carry the implement it powers. As its inventor Beaujot has explained during early public demonstrations when his company owned the machine, that is a more efficient concept than using a ballasted tractor to pull a tool through the field, which requires horsepower and fuel consumption to power its own weight and create enough traction to do the job. Dot uses the implement’s weight to create traction. It’s also what makes its design significantly different from what the major brands have shown in the field of autonomy.

Dot’s original corporate owner, SeedMaster (as the parent company of Dot Technology Corp.) will continue to manufacture the specially designed 30-foot seed drill designed to mate with it, as well as a trailer for road transport. Currently, two other firms are producing a unique implement designed to mate with the machine, New Leader, which builds a dry product spreader and Pattison Liquid systems that builds a 120-foot sprayer.

Morson doesn’t expect the look of Dot to change much after R&D is completed. “It will still be the U frame,” he explains.

One of the things the company has evaluated is the available horsepower, but Morson thinks it’s adequate as is, and that is unlikely to be increased in the near term, unless the company sees a popular demand from customers for more.

The most important changes to Dot will likely be in the technology used to control it. Raven has integrated some of the sensors and systems used on its other autonomous project AutoCart, which is a system designed to allow a tractor to pull a grain cart in a field at harvest. The company claims AutoCart will soon be commercially available along with Dot.

“Raven really listened to the employees and they’re giving us the resources and the time to put this in the field and really test it with customers,” Morson adds. “So we’re not just running in circles on a cement floor, we’re putting it on hills, in broken-up fields with sloughs and trees, the same challenges our future customers would have…”

As engineers consider whether or not there is room to add any fine-tuning tweaks to the platform, Morson believes the R&D program has proven Dot is fully capable of being let loose in customers’ fields and the evaluation program is very much on track.

“I really wouldn’t want to see a spin on this that the product is not ready and not on the timeline we want,” he says. “It very much is.”

But while Raven’s R&D puts a lot of effort into ensuring safe and accurate navigation, other developers focus on the agronomic end of things instead.

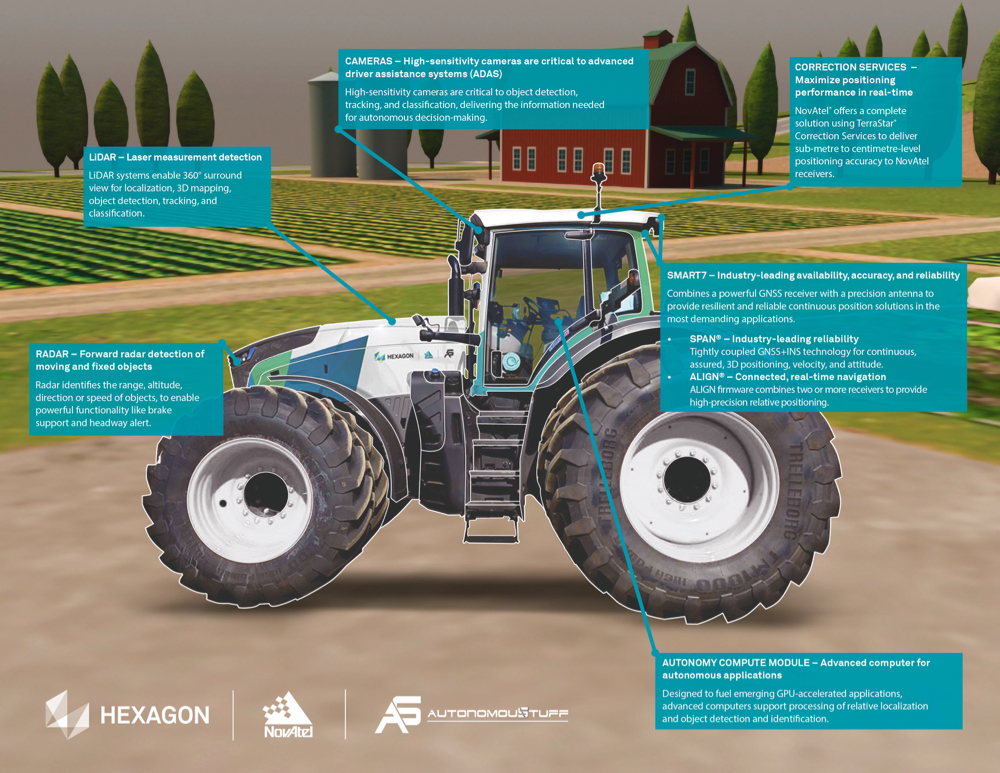

“There are other manufacturers that are focusing on identifying and classifying objects for the agronomic task, such as identifying a weed to spray versus not spraying a corn stalk, or what strawberry to harvest versus which one to leave there,” says Tanner Whitmire, agriculture business development manager at Hexagon/NovAtel, also in North America. “Those are the areas we see the OEM manufacturers focusing their efforts on, making sure their robot performs the agronomic task.”

That has left a space for technology companies to fill when it comes to creating highly developed navigation and obstacle recognition sensors and software. Here, NovAtel, has found a niche. It is developing software and sensor system options, intending to be a component supplier to manufacturers when more of them move into autonomous and semi-autonomous machine production.

The company has worked jointly with Autonomous Stuff, which is also part of Hexagon, in the development of autonomous vehicle operation R&D in both the on- and off-road sectors. This fall, it has been preparing to demonstrate its latest autonomous navigation and human detection developments. The company built the system into a Fendt 1000 Series tractor.

Whitmire says the Hexagon project focuses on two main areas: positioning and sensing.

While NovAtel and Autonomous Stuff have been involved in working with GPS navigation systems for some time, the system on the demonstration tractor offers some advances. For one thing, it can detect its direction before any movement occurs, unlike many agricultural systems that require a tractor or machine to start moving before it can orient itself and head in the right direction.

“The benefit here is you have an accurate heading upon startup,” he says. “So there’s no movement required. Today, the systems require the driver to move the vehicle to calibrate the sensors internally. It will give better navigation accuracy at lower speeds. And by adding some of the perception relative localization-type sensors, we can provide a better position and more reliable solution than just GNSS only.”

That accuracy requires a system capable of reading input from more than one antenna and sensor.

“The second piece, when we move into autonomy, is situational awareness to make sure the vehicle is moving safely,” he continues. “There’s a couple of different ways to do that. One of the main points I commonly hear (from OEM developers) is we’re not sure what type of sensors we would need when it comes to perception for identifying a human or detecting an obstacle. Can you use a LiDAR, or can you get by with a camera? Do you need a thermal camera? So our demonstrator vehicle is equipped with multiple types of sensors.”

Each of those sensor types has its advantages and disadvantages, and using them in an agricultural application can pose even greater challenges than for on-road automotive uses.

“LiDAR is great for a point cloud obstacle detection standpoint,” he explains. “But it’s not really great for detecting objects in rain or heavy dust, which in off-road agriculture are two weather patterns that are going to be common, especially dust.

“So we’ve added cameras. They’re great for obstacle classification and identifying a human. We also have thermal (cameras), which can help through those other weather conditions. But one thing that is challenging for a camera is identifying the distance. So you can detect it, but you’re not sure where the vehicle is compared to where the human is.

“These are the technologies our demonstrator vehicle highlights. It’s going to be a combination of multiple sensors infusing those technologies together, which is one of our areas of expertise.”

But identifying the proper sensor — or sensors — is just the first step. From there it’s about putting together a fully integrated system that can not only see where it’s going but understand what to do with the information it’s receiving.

“It’s about deciding what a vehicle can drive through or over, versus what a vehicle needs to stop for,” Whitmire says. “Today in the demonstrator platform, we supply the sensor kit, so to speak, that includes a computer that would process the information, but the kit is a foundation for developers to build their own software applications off of.

“We’re building software stacks that can easily be integrated into various types of autonomous vehicles for agriculture that can annotate the data and identify humans. The reason we’re going with humans is it seems to be the highest priority from an identification standpoint.”

While companies like Hexagon work on technology that can interact with human traffic, how are humans reacting to autonomous machines working their fields?

“The excitement from the customers when they see an autonomous machine in the field is something else,” observes Morson. “You come across the odd naysayer, who mentions corporate farms and says these will take away jobs. But the reality is a family farm now in Western Canada is 4,000 or 5,000 acres. They just don’t run an operation that can employ the six to 10 guys they need during seeding and harvest. So we need solutions like this that can help get the job done. Our labour pool is just so short. We’re running out of grandpas, uncles and old retired farmers that can come and help out for a few weeks at harvest. Something like this autonomy is really needed.”

But is the state of autonomous technology really a threat to farm worker jobs just yet, or will it take a while for that to happen? In 2019, Country Guide had a chance to speak to Dustin Burns, a Saskatchewan farmer who was one of the first to purchase and use a DOT for the 2019 season.

“At this stage it’s not going to replace what people currently do,” he says. “You can’t just change everything over.”

His farm currently operates three 90-foot drills during spring seeding, and the one DOT running a 30-foot drill hadn’t made any of them redundant, but that was mainly due to the fact the autonomous DOT was still largely in the development phase and initial safety regulations meant it had to be continually supervised during operation.

“We don’t want nine operators instead of three (to replace the three 90-foot regular seed drills), so obviously the first step is we need nine DOT units that can be managed by a single person,” he said. “Maybe that number is three. Maybe it’s more than three. Maybe it’s limitless; we’ll know as time goes forward. But that’s when we’re going to be seeing efficiencies.”

In the meantime, both Raven and Hexagon continue to fine-tune their products and advance the state of autonomous ag equipment, while at the same time keeping in mind farmers need to accept this new technology.

“We’re trying to build trust with growers so we really have to start at the top,” notes Whitmire. “With these new ways of integrating these new solutions, it really starts at the suppliers and integrators, and that needs to channel and funnel down into the OEMs. Plus we really need to educate the OEMs, so they’re versed in the technology. So when the technology does make it into the growers’ hands, it seamlessly integrates into their agricultural workflow.”