UPDATE, Feb. 13, 2016: Iain Stables is to appear in Provincial Court in Saskatoon on April 14, 2016, facing 29 criminal charges relating to missing farm equipment and machinery RCMP reported found on a rural property south of Delisle, Sask. Click here for more details on the charges. The allegations have yet to be proven in court and Stables is presumed innocent.

SECOND UPDATE, Aug. 29, 2017: Saskatoon media reported Aug. 28 that Iain Stables has pled guilty on 18 counts from last year’s charges. Click here for more details.

Read Also

Lessons from the past: How Canada can reverse its shrinking share of the global food market

A historic look back at how Canada has positively dealt with trade issues — and how those lessons can inform future moves.

THIRD UPDATE, Dec. 15, 2017: Saskatoon media reported Dec. 15 that Iain Stables has received a conditional sentence of two years less a day, to be served in the community, plus three years of probation and a restitution order worth $111,000, following his guilty plea in August. Click here for more details.

In 1859, a Scottish aristocrat travelled through much of Western Canada in pursuit of big game. He rode the endless, remote expanse, joining a buffalo hunt in west-central Saskatchewan, for it seems that it was here that our Scot — the ninth Earl of Esketh — got wind of an even greater adventure to be had not far away. So off he went again, this time in search of a Plains grizzly, venturing with his horse and tracker into the Bad Hills range, a 10-mile wilderness of hills and deep ravines known as prime bear habitat.

There, with the help of a Cree guide, he bagged his grizzly. And there too, some 65 years later, another Scot, this time named Bob Stables, settled the rugged hills near Rosetown. But Stables, in his way, was after even bigger quarry.

Stables was a cattleman, and he went on to build up a Black Angus herd that he named the Isla Bank Angus, after the River Isla that wound its way through his family’s farm back in Scotland.

But the story doesn’t end there. Fast-forward the better part of a century, and you’ll find Iain Stables who grew up on the Bad Hills ranch founded by his great-uncle, and who now with his fiancée Jamie Van Cleemput is carrying on the Isla Bank herd name, although not on the original property.

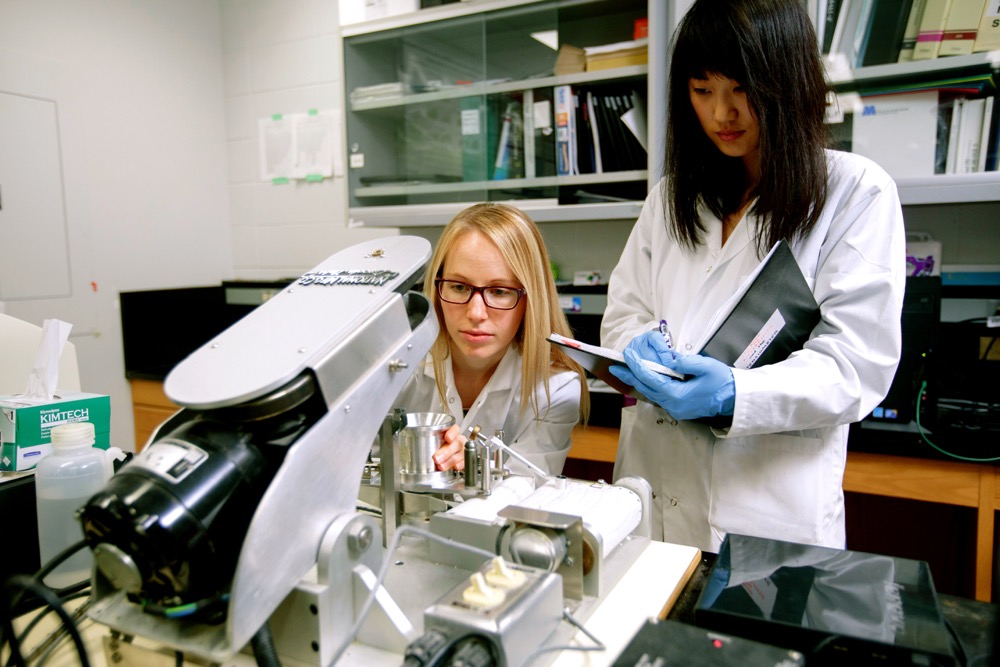

Jamie and Iain met at Innovation Place, a hub of science and technology that butts against the University of Saskatchewan. “We actually worked across the hall from each other,” recalls Jamie.

Jamie, who holds a graduate degree in science, was working for a pharmaceutical company and Iain an agricultural company. She had grown up in Saskatoon and Calgary, and she laughs now at how adamant she had been that she wasn’t going to end up on a farm. Her parents owned the first Taco Time franchises in Canada, and also owned restaurants in both cities, and she knew all too much about the travails of small business.

“Our income and our day-to-day life was so influenced by other people that I always wanted stability,” Jamie says. “And when you look at farming, that’s kind of the opposite.”

But things took a turn that she hadn’t planned.

“I gradually moved her out,” says Iain.

They first settled on an 80-acre place, owned by a friend, south of Saskatoon. Then, four years ago, they moved farther out, to a ranch south of Delisle, about 40 km southwest of the city.

Iain always wanted to ranch, but his return to the farm wasn’t a straight line. After earning an agriculture degree from the University of Saskatchewan, he ranched with his dad for a while. But they didn’t have the land and cattle to support both of them, and his dad wasn’t ready to retire.

So Iain went back to university and got a diploma in animal science. He started working, and although he still owned some cattle, he didn’t go back to the farm for years.

Then, in 2007, Iain’s parents dispersed their herd. Iain and Jamie were living on the 80-acre farm by then, and Iain still had cattle in the Bad Hills. But they didn’t have room for all the cows Iain had retained over the years, so he had to sell over half.

“It’s not hard to source new stuff from other producers,” says Iain. But losing a line he’d curated for generations meant losing cows he knew — Iain says he could recognize an individual cow from his original herd from 1,000 feet and tell you what kind of calf each cow could produce.

“And when you start bringing in other ones, it’s amazing how it takes you two, three years before you get that same familiarity with them,” Iain says.

There have been a few bumps on the road to ranching life for Jamie, too. She says there is a bit of a stigma around being a city girl. When people hear about her urban background, she chuckles, they aren’t sure what to do with her.

The other challenge is learning to work cattle. “I keep getting told I don’t have the common sense of the rancher because I started chasing cows when I was 30,” she says. “You hang out with people who started chasing cows when they were three, and they don’t really realize what they’ve learned.”

But Jamie seems to handle it with good humour. She jokes about being a human cattle gate and pylon. And despite the steep learning curve, she’s well suited to ranch life.

For one thing, she’s a workhorse. At Canadian Western Agribition in Regina last fall, she clocked long days shovelling manure and caring for Isla Bank’s show cattle. She comes by that work ethic naturally.

“I was an only child and both parents had to run their own stores. So I spent every school vacation in the store working,” she points out.

Others have also noticed that work ethic. Since she left her full-time job, she’s been helping at the cattle shows, and she says others are more accepting of her now that they know her better.

Besides, both she and Iain have specific skills that come in handy on the ranch. Jamie describes herself as a Type A personality, so she focuses on customer service, marketing and registrations. She also creates websites and does graphic design for other livestock producers.

“Anything with a deadline seems to be my calling,” she says.

Iain knows every cow in his herd. He’s got a solid background in animal science and genetics. He also handles the daily feeding and runs the equipment.

Iain did retain some of his original Isla Bank cattle and has been rebuilding the herd. These days he runs 100 head. About 70 are purebred, and the other 30 are commercial cows that carry purebred embryos.

Jamie and Iain are trying to expand, but buying land isn’t easy in the Delisle area.

“We’re competing on the basis that it has to make money, whereas some of the people who are maybe more established, they don’t necessarily need a return from it,” says Iain.

Iain and Jamie aren’t the only ranchers struggling to expand. In fact, some potential beef producers found the hurdles too high to jump to even enter the business.

The multi-year price slump for cattle meant the returns didn’t justify the next generation taking over, unless they were working with family members, Iain says. Better beef prices should help young people wanting to take over, he adds.

But Iain wonders if poor returns have chased a generation away from beef production. Many are in their late 20s or early 30s now, settled into other careers.

“Even if you grew up with it, if you move away from it for 10, 15 years, you lose a lot of that stuff that you knew,” says Iain. Many active ranchers are older, and he wonders who’s going to take over once they retire. And Statistics Canada backs him up: In 2011, most beef producers were 55 years or older.

Iain and Jamie have found ways of dealing with the challenges of establishing their own operation.

Ranching on their own means they can’t share equipment the way some farming families do. But they didn’t want to run old equipment and deal with breakdowns. So instead they did a lot of custom haying to offset new equipment costs. They don’t do as much custom haying these days, but they do custom bale picking with their self-loading bale truck.

“You have to be diversified,” says Jamie. They’re also looking at a couple of job offers that would allow them to retain their own herd while tucking money into the bank, so they can eventually expand their own operation.

Whatever they decide to do, they intend to stick it out in the ranching industry. The Isla Bank herd name has survived for over 75 years, and they’d like to keep it going. And besides, they both love the industry.

Iain cites working with cattle as a joy, and says walking through the herd when they’re on pasture in the summer is hard to describe.

But there are annoyances too. Jamie says part of it is fighting perceptions about “factory farming” and “some of the lovely documentaries that come out when that’s not what we see outside our window” and nobody they know functions like that. She says farmers need to start telling their stories from a personal angle.

She points to Iain, who sees cattle as livestock which will eventually be slaughtered, but while they’re in his care, they should be treated well. “They can’t see that,” Iain says. “I don’t think any amount of arguing with them will get them to see that.”

Jamie tweets on #farm365, and she tries to use other opportunities, but she also says she knows she’ll never change the extremists’ views. “But they’re the most vocal ones, so I don’t want their claims to go unanswered. My goal is to really show that we do care about our cattle and we do care about what we feed people.”

Jamie adds it’s easy to have an opinion about someone when you don’t know them. When ranchers and farmers share personal experiences on Twitter, however, it’s harder for activists to make those claims because everyone can see they’re actual people.

Her goal is to clear up misinformation and share pictures from their ranch. “It helps give the human side to the ranching story. It’s not just a factory that spits out calves and steaks.”

Jamie’s impression of farm living was that it was really hard, she says. “It’s a lot of work and it’s up in the air all the time. You have to worry about weather and all sorts of different things so it’s just a hard, stressful life.”

But both of them like the community. Beef shows are like family reunions, even though that’s the only time they see many of their fellow cattlemen, says Jamie. And agricultural communities, she adds, are good at pulling together.

But that sense of community is balanced by the freedom of running their own business.

“You’re independent,” says Jamie. “You can guide your life the way you want.”