The farmers were smiling. They were attending one of this country’s premier machinery expos in Gunnedah, New South Wales, and the weather forecast was calling for widespread rains across the region. In Australia, that is a reason enough to smile.

Rain in this country is a precious and sometimes scarce commodity. Even a few millimetres can lift farmers’ spirits.

The machinery reps who work the show’s exhibits know the pattern too. Across much of the state, they’re used to seeing the fortunes of its farmers ebb and flow on a five-year cycle that is driven by rain — or the lack of it. For two of the five years, there’s very little moisture and crops are poor. For another two, adequate moisture provides a fair crop. And then there’s that one bin-busting, golden year that makes up for all the others.

Farmer Scott Doyle summed it up as we stood on the edge of a canola field on his 2,000-acre farm about 15 minutes from the city of Tamworth, a four-hour drive north of Sydney.

Pointing due west toward the town of Gunnedah where the Commonwealth Bank AgQuip Field Days machinery show is held every year, Doyle says, “Over those hills, that’s the Liverpool Plains. It’s never gone without growing a crop, it’s good soil, whereas we, if we don’t get rain…”

Doyle doesn’t need to finish the sentence.

In northern Australia, an extended drought and unexpected restrictions on exports of live cattle to Indonesia (their biggest market) have virtually bankrupted large numbers of livestock producers. To the south, by contrast, most of New South Wales has fared much better despite low precipitation in the last couple of years, and this year crops also look good.

Read Also

Where convention and innovation meet

How one Ontario farm is integrating technology into their beef operation.

At the AgQuip show, there were a few Canadian-built no-till drills and air carts on display. Many farmers, including Doyle, have made the switch from tillage to no till in the last decade. It required a leap of faith, just as it did for Canadian farmers.

“I haven’t tilled since I’ve been doing zero till,” Doyle says. “And I’ve been doing it since about 2005. I just jumped off and went into it. And the first year I thought, what the hell have I done, because the crops didn’t yield all that well. But as the system gets going, the yields get better.”

Initially, Doyle’s neighbours were skeptical too, but no till has helped manage their moisture limitations in Australia.

Now, however, other concerns are emerging, and Doyle expects to go back to some tilling in the future. “We will have to till,” he says. “We’ve found diseases and spray resistance. That’s our big thing, because we’re very reliant on Roundup.”

Canola is a winter crop in Australia, and Doyle expected to be harvesting the field by October. However, on this day in late August, there was still some risk of frost, which is a problem that accounts for a lot of lost yield on winter crops across many grain-growing areas of the country.

Across the fence, a herd of black cow-calf pairs were grazing. Cattle can graze year round, but it’s common practice to seed an annual crop and turn them into it to increase their rate of gain.

“That green paddock, that’s oats we put in for winter,” Doyle says, looking off in another direction. “That tops them off a bit. Then in the summer we put a forage sorghum or a legume in. There are natural grasses, but you need to put a crop in to get the fat score up.”

The Doyle family has farmed this land since it was acquired by his grandfather through a state-sponsored veterans’ program. Now he and his brother, Lindsey, are in charge.

They call it a station

Warren Hobson’s farm south of Boggabri is still described as a station — “Quia Station” to be exact. I met him when I stopped at an isolated crossroads in an area of the Liverpool Plains that is made up primarily of broad-acre farms, very similar to Western Canada.

Hobson was making a liquid nitrogen application to a barley field that he had allowed his cattle to graze on earlier in the winter. Farmers in the region generally wait to see what growing conditions are like before committing to a full fertilizer application. With the news of rain in the forecast, it made sense to start topping up inputs.

Hobson uses some tillage to control weeds and deal with other problems as needed. “A couple of tillage passes and a spray each season,” he says. There is no-till equipment in his shed but glyphosate resistance is a problem, as it is almost everywhere in this country.

The crops in this area looked good as well, but water reservoir levels on Quia Station were running low, especially in dams built to supplement well water supplies for livestock.

“They’re 18 feet deep, but there is only about a foot of water left,” explained Hobson.

Metal or plastic water storage tanks are a common sight in both urban and rural locations. The Hobsons’ station also uses them to collect rainwater run-off from machinery shed roofs.

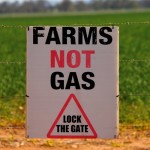

The Liverpool Plains actually sit on a large aquifer which feeds deep-water wells and allows these farms to exist. But many farmers think its water supply may be in jeopardy from proposed energy and natural resource development. The pending startup of another open-pit coal mine and proposals for shale gas development in the region are causing concern. Environmental studies made public suggest the risk to the area’s underground water supply is minimal. But locals aren’t convinced.

For them, any risk is too high. Without well water in an already dry region, there is no future for farmers.

For them, any risk is too high. Without well water in an already dry region, there is no future for farmers.

The defiant sign Hobson wired up at the entrance to Quia Station, like those at so many other farms in the area, says it all: “Farms not gas. Lock the gate.”