Bag-toting shoppers amble past me on either side as I snag a table near the bakery. It’s already 2 p.m., and the picked-through bakery racks confirm that it’s too late to get the best-of-the-best fresh food at Toronto’s St. Lawrence Market.

Even so, the place is still a hive of food lovers. That’s because by midday, the shoppers change. The hard-core grocery browsers give way to a hard-core, hungry lunchtime crowd.

Either way, they love their food. They also know a lot about it, and it looks like they want to know more, although I wouldn’t take any bets on how much they know about Canada’s farms.

Read Also

Sibling squeeze part 6: The emotional stakes of a family legacy

The final instalment in a six-part series exploring the challenges of sibling conflict and the effect it can have on…

Along with the lunchtime crowd and grocery shoppers, though, some people just come to hang out and chat — people like food writer Lynn Ogryzlo and me. As coffee spots go, the floor-mounted melamine table with attached plastic chairs we sit at isn’t pretentious — and neither is Ogryzlo. I’ve barely shaken her hand before she apologizes about the garlic smell from the pastry she’s brought to munch on during our meeting.

I’ve been hoping to meet Ogryzlo because she’s a food columnist who talks a lot about what many food writers don’t: farmers.

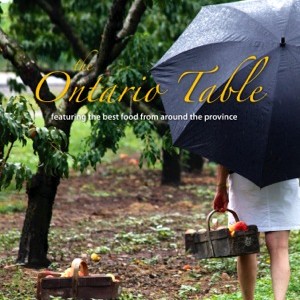

In her 2011 bestselling book, The Ontario Table, Ogryzlo serves up recipes for Ontario-grown food, pairing each recipe with a blurb about a farmer. There are grower stories, recipes, and culinary destinations. A column on farmer Fred de Martines and his Tamworth pigs accompanies the recipe for pork patties with nectarine relish, while the page on simmering beef features the O’Brien Farms Simmental herd at Winchester, near Ottawa.

It’s more than just a cookbook, and Ogryzlo takes a hard-to-define, sometimes disparaged concept — local food — and boils it down into a clear, compelling message called the $10 Challenge. It’s nice marketing: $10 each and a billion-dollar impact.

She explains in the book, “If every household in Ontario spent just $10 of their grocery budget on local foods each week, there would be a $2.4-billion influx into the provincial economy each year!”

In a world where farmers complain they’re misunderstood and ignored by consumers, Ogryzlo might be our best indication of what happens when a person of good intentions, open mind, and an intelligent curiosity begins to look closely at their food.

- Another ‘Local food’ success story from Country Guide: From a modest start

The culinary activist

A self-described “culinary activist,” with a focus on locally grown food, Ogryzlo is quick to make the distinction between activism and extremism. She recounts travelling to Chicago and making a social media post about Chicago food. She was shocked to get an indignant response from a follower who was upset that the post hadn’t been about Ontario food. She shakes her head, saying, “It’s not absolute.”

Another time, she met someone who hadn’t eaten a mushroom for a year because he couldn’t find locally grown ones. “It doesn’t matter,” she exclaims, adding, “It’s not a diet, like the Atkins diet or Weight Watchers diet! That’s not the point.”

The important point, she feels, is that shopping with local food in mind has the power to make farming sustainable for farmers. It requires neither absolutes nor a black and white, 100-mile-diet dogma. (Although she does like the book The 100-Mile Diet because it gets readers thinking about the food system.)

Food and community

Ogryzlo grew up in the community of Thorold in the Niagara region of Ontario. The granddaughter of Italian immigrants, she describes it as a community with a heavy Italian presence where people hung out on front porches to chat. She remembers the farm truck picking up local women to work on nearby farms, and, at the end of the day, the women being driven home, legs hanging over the tailgate, balancing bushel baskets of seconds for their own use between them.

“The people who worked on farms were the people who lived in our neighbourhood,” she recalls. It was a community where food played a pivotal role. If there was extra produce in those bushel baskets, it was shared, with a jar of some sort of preserve given in return at a later time. Food was used to celebrate, to mourn, and to nurture the sick. “It made us a really strong community,” she says.

It’s still that power to foster community that she sees in food — and in people’s shopping habits — today.

Her own community — the Niagara region — used to include 20 canning factories, she says. But now there are none. Today, she sees more tourism. That’s fine, but she feels there is an opportunity to attract tourists for agriculture too. That was the idea when she helped found the Niagara culinary trail, a culinary tourism organization connecting consumers to farmers.

The Ontario Table

The Ontario Table is Ogryzlo’s third book, following in the footsteps of Niagara Cooks, from farm to table and Niagara Cooks, a seasonal approach. For this book, she explored beyond her home base of the Niagara region, taking weekend trips over two years to different parts of the province to meet farmers and taste food.

Her regionally focused books and local food have some parallels: both are on the fringes of conventional marketing and distribution channels.

“In the publishing world, everyone thought I was nuts!” she tells me with a laugh.

In the book, Ogryzlo tells readers not to worry about following recipes to the letter. She hasn’t followed the standard publishing recipe to the letter either, opting instead to self-publish her books. It has worked out well, as all three have been bestsellers, and she has won a number of international awards.

Without the distribution infrastructure that a publisher would have, she built her own network, selling books through on-farm stores, including many of the farms featured in the book. “It’s the largest margin item in their store,” she says. Eventually, the distribution channels came to her because of consumer demand for her books.

$10 challenge magazine

While The Ontario Table includes a section that lists suppliers of things as diverse as soy sauce, salt, flour, nuts, and cornmeal, Ogryzlo found that people still had difficulty with the shopping side of eating locally. In response, she did more travelling and then put out an electronic magazine (now combined into an e-book) called The Ontario Table $10 Challenge, a year of eating local, in which she worked with 25 agricultural commodity groups to get facts for consumers about Ontario food.

Markets and farm gate stores are great, she says, but they aren’t the only way to support local farmers. When it comes to shopping for local food, Ogryzlo tells me, “The grocery store is a good place to find local food.” She laughs as she describes trips to her local grocery store and people peering into her cart to see what is in there. While some people connect the idea of local only with fresh produce and meat, Ogryzlo includes all foods raised and produced in Ontario. That can include common things such as meat, tinned goods and dried beans.

Industry playing catch-up

Ogryzlo feels that consumer confusion about the definition of local food is a result of the movement being a consumer-driven — not industry — trend. “The local food movement sweeping the country is led by consumers and I think this is the very reason we face challenges such as lack of distribution and an agreed-upon definition of local food,” she says. It’s a case of industry catching up to consumer demand.

In the meantime, Ogryzlo is gearing up for a new audience. She and her husband have just moved from the Niagara area to Toronto — and she’s looking forward to writing for a new slate of publications. She says she has always wanted to live in a big city. “Toronto was more doable than Paris,” she says with a chuckle.

She’s not at all worried about missing out on farm-fresh produce in the city. “In the city, people are more fortunate,” she says as she talks about urban markets often attracting more farm vendors than smaller centres.

When it came to picking a neighbourhood in Toronto, food was important — so she’s not far from the St. Lawrence Market. As we finish chatting, we leave the table in the bakery aisle. We head our separate ways, each of us to shop.

I keep my eyes on all the consumers in this one market, and I have $10 in mind.