On-farm research is one of those things that sounds great in theory, especially with the technology at hand today. But how can agronomists and farmers reap results they can use, and count on?

Saskatchewan crop consultant Mike Palmier offers one case study. Working with a farming client, he’s found that leaving taller crop stubble in the fall can improve the odds of higher crop yield in the following year.

His field observations in the 2021 growing season, followed by on-farm research trials through 2022 and 2023, produced data to support a recommendation to leave taller crop stubble. Even a couple of extra inches will trap more snow, which will increase soil moisture and lead to higher yields.

Read Also

Government silence loud on AAFC cuts

Canada’s federal government trumpets fiscal responsibility; their silence on a day of massive Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada cuts was baffling at best.

“The research showed that every extra inch of stubble height can serve to trap more snow and lead to more moisture for the crop the following year,” says Palmier, owner of Max Ag Consulting at Plenty, about 70 kilometres northeast of Kindersley. “Our 2023 research showed that every extra one inch of crop stubble can increase canola yield by 1.1 bushels per acre.”

He notes there are several variables — there must be snow to start with — but the field trial showed that grain stubble left even two inches taller can result in a canola crop producing two more bushels of oilseed per acre. At about $13 per bushel, that’s a value of about $26 more per acre. The only management change needed is to raise the combine header two inches higher.

Palmier’s look into the value of stubble height began with a couple of harvest situations in fall 2021, which led to the on-farm research trial in 2022. The growing season was dry in 2021, but in one area there was moisture before harvest that caused a lot of volunteer regrowth in one canola field. It was difficult to harvest the standing crop, resulting in a lot of tall stubble.

In another situation, again due to the dry growing season, a producer left part of his canola crop unharvested because of poor yields. Both cases left tall or fairly heavy standing crop residue that trapped and held snow.

“In the early part of harvest in 2022, the yield data showed that something was affecting yield on these fields that had standing stubble and unharvested crop from the previous year. Were higher yields in these areas due to taller stubble trapping more snow and ultimately more moisture for the subsequent crop?”

Working with the producer, he launched the on-farm research trial that fall to find out.

Good support from client

Palmier was working with a client who was anxious to learn more about the value of crop height and trapping snow to improve yield. That producer had already invested in two types of harvest systems — two combines equipped with stripper headers and one with a conventional header.

The plan was to establish field scale plots of about 20 acres with varying stubble height in a field of durum wheat. Some plots were harvested with the stripper header, leaving stubble as tall as possible, and other plots were harvested with a combine equipped with a conventional header.

“It’s common for many producers to leave stubble about eight to 10 inches tall. The producer I was working with didn’t want to cut the durum crop that short. He was pretty confident that taller stubble could trap more snow, so he wanted to capture as much moisture as possible and still provide a comparison.

“So, the stubble with the conventional combine was cut a bit taller than average but not as tall as the stripper header stubble.”

Palmier says durum stubble height was 18 to 20 inches in stripper header plots and 12 to 14 inches in the conventional header plots. The producer was already using variable rate technology in his fields.

A variable rate mapping system had identified 10 different production zones on the field and research plots were established in several of those zones. The producer was already using Bayer’s Climate Fieldview technology with GPS tracking, so it was used to measure and mark 20-acre plots for the project.

The durum field was harvested in fall 2022 with 20-acre plots all in the same field. Some were harvested with the stripper header and others with a conventional header. All that was needed was snow, and it did come.

“There was a fairly early snowfall in the fall of 2022, which was captured in the stubble. And prevailing winds are important as well. Typically, in this area, winds are from the west, but in the winter of 2022/23, we also had winds from the east. As winds change direction, they help to carry more snow into the stubble.”

He says it is important to note that the 2022 growing season and harvest conditions were extremely dry, so there was no immediate topsoil moisture heading into winter. Without moisture, the soil didn’t freeze so it was receptive when the snow did melt. There was no runoff.

Measuring snow density

The field was left for the fall and winter until February 2023, when Palmier measured the amount of snow and moisture held in the various stubble heights.

“For the snow survey, we collected 10 snow samples from both conventional and stripper stubbles to weigh for snow density. We also measured 30 points in both stubbles for snow heights to estimate the average snow height in both treatments. By combining both these measurements, we could then understand what our average snow water equivalent was in the two treatments.”

Palmier noted snow density in the stubble varied between the two harvest treatments. The snow in the stripper header stubble had about 25 per cent moisture, while the conventional stubble had about 27 per cent moisture. He suspects the difference in density was due to the conventional stubble moving more with the wind, allowing the snow to settle, while the stripper header stubble was more rigid.

“Even though the snow in the conventional stubble had more density, there was less of it. Whereas the snow caught in the stripper stubble was less dense, but there was more of it due to increased stubble height. Ultimately the stripper header stubble held 20 mm more moisture than the conventional stubble.”

After the snow survey, the field was left until seeding. As spring approached, snow in the stripper header stubble melted sooner than that in the conventional stubble, likely because there was more exposed stubble on the stripper header plots to attract solar energy. Because the ground wasn’t frozen, any moisture went straight into the soil.

Soil moisture probes are key

The final bit of important technology needed to monitor the research project was an on-farm weather station outfitted with soil moisture probes. The project used a Crop Intelligence RealmFive weather station that wirelessly connected to two John Deere moisture probes.

“We set the weather station up at the edge of the field and placed the two soil moisture probes in the same field. One was placed in the stripper stubble plots and one in conventional stubble plots.”

The field was seeded to canola with a disc drill on May 16, and the soil moisture probes were installed May 21. The probes were connected wirelessly to the RealmFive weather station by a flex station, which pulls data from the probe. The station contains a modem and SIM card, where it can upload data to the cloud. It is stored and processed on Crop Intelligence’s platform.

The John Deere soil moisture probes have six sensor points at varying depths along the 100 cm length of the probe. Palmier used a three-inch diameter hand-held auger to create a hole the right depth for the probe. To ensure proper soil contact, he first made a slurry of soil and water to fill the hole and then pushed the probe into the slurry.

Once in soil, the probes’ sensors provide soil moisture readings at intervals from 10 cm to 20 cm, 30 cm, 50 cm, 70 cm and 100 cm (from four inches to 40 inches). He says it is important to know the soil type to understand its moisture-holding capacity. Clay soil, for example, will have a plant wilting point with a reading of 20 per cent soil moisture and a maximum moisture-holding capacity of 50 per cent moisture. Sandy loam, on the other hand, will have a wilting point of eight per cent moisture and a maximum holding capacity of 32 per cent moisture.

“It is important to know soil texture. The probe will only tell you how much moisture is present, so if it says 32 per cent and you have sandy loam soil, you know the soil is at moisture-holding capacity, but if it is 32 per cent and your soil is more clay, you know you are a long way from moisture-holding capacity.”

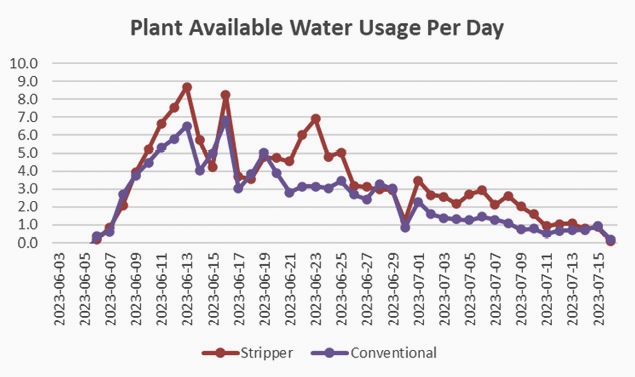

For the 2023 growing season, Palmier measured about 20 mm (roughly 0.8 inch) more plant available moisture at the start of the year on the stripper header strips than on the conventional header strips.

The rest of the growing season was not particularly kind to the crop. From May until mid-August, there was just over 82 mm (three inches) of rainfall. The biggest rainfall after June 3 amounted to 11 mm, or less than half an inch. Overall, it was about 39 per cent of the average growing season rainfall. And on top of dry conditions, there were plenty of hot days. Between June 5 and Aug. 15, 22 days were 30 C or hotter.

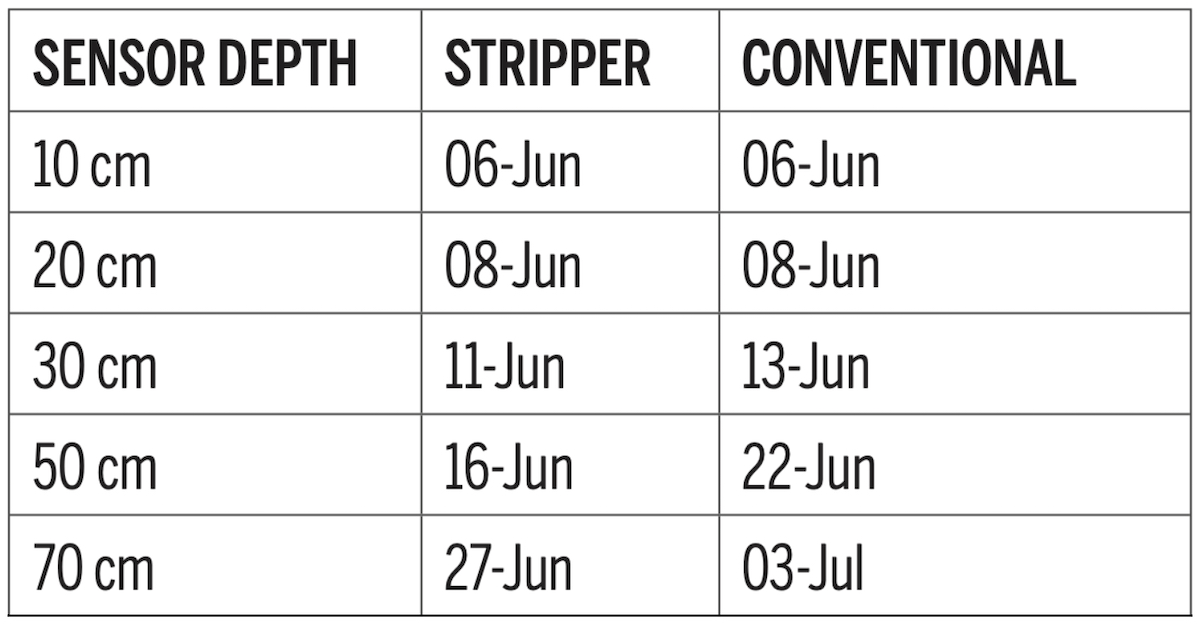

On the field with alternating strips of crop grown on tall and shorter stubble, canola plants showed a difference in growth pattern. Palmier says the roots on two treatments reached the 10- and 20-cm depths at about the same time. After that, the crop seeded on the stripper header stubble reached 30 cm two days earlier, and 50 cm and 70 cm depths six days earlier than the short stubble crop.

“That tells me the crop on stripper header stubble appeared to be more vigorous. It had moisture but also the taller stubble most likely helped to reduce abiotic stress factors by providing more shade to plants and protecting plants from the wind and other stressors,” says Palmier.

He also found that the crop on the stripper header stubble started the year with more moisture and ended the growing season with less soil moisture than the shorter stubble crop. Again, it was an indicator of more robust plants that developed more roots and used more moisture.

Overall, the crop with taller stubble yielded six to eight more bushels per acre than crop grown on shorter stubble.

Palmier says not every farm can handle stubble that’s 15 to 20 inches tall, because not every seeding system can work through that much standing crop residue.

“But the point is, if a producer can leave stubble even two or three inches taller — go from eight to 10 or from 10 to 12 inches — it can make a difference in how much snow is trapped and how much moisture is available to the crop.

“There are only so many things we can control, but we can set things up to take advantage of snow and moisture if or when it does come. And particularly during extremely dry conditions, every little bit helps. Small changes in management can make a difference.”

Palmier planned to monitor fields with crops seeded into different stubble heights during the 2024 growing season as well.