The clash between generations over outlooks, opinions, values and beliefs dates to ancient times.

In fact, this disparity of perspective has a name: the generation gap.

Each generation is shaped by the predominant forces at play during their formative years. Acknowledging these influences can improve communication among the generations, says River Falls, Wisconsin leadership development coach Kristin Pronschinske.

Read Also

Lessons from the past: How Canada can reverse its shrinking share of the global food market

A historic look back at how Canada has positively dealt with trade issues — and how those lessons can inform future moves.

The popular international speaker on intergenerational communication says advances in technology have had a big influence on people of different ages. Many of those in the silent generation (born 1928-1945), for example, grew up in a time before electricity and phones. Contrast that with the iGeneration (a.k.a. gen Z, born 1997-2012), who have never known a world where the internet didn’t exist. And the youngest generation, gen alpha, is said to “be born with cell phones in their hands instead of rattles.”

This generational gap in communication styles can result in some muddled expectations around the outcome of a conversation or decision.

For example, when the younger generation has new ideas about how things should operate on the farm and beyond, it can set the stage for conflict and tension, especially where farm transition planning is concerned. It’s a pattern that’s playing out on many farms across Canada, says Humboldt, Sask. succession coach Patti Durand.

“A good rule of thumb,” she says, “is to be more curious and less judgy,” although she acknowledges how tough this is to do — and it’s even harder to do when you are the parent, whose job it has been to guide and teach the younger generation. “As our kids age, we may fail to recognize they are capable. Old habits are tough to break,” says Durand.

She says that when working with family, there is an opportunity to dig deeper to better understand someone’s words and actions, rather than quickly labelling or criticizing them.

One oft-repeated criticism of younger generations is that they are spoiled or soft. Durand advises that if you feel you have “a spoiled next generation,” pause to consider what you may have done to create or enable that behaviour. “This is not excusing their actions but knowing they did not get there alone.”

Generational conversations

When it comes to having difficult conversations, Pronschinske replaces the word “difficult” with “important.” Her advice: “Leave emotion and judgment out. Don’t focus on negativity. Speak to facts and data. Ask questions and listen. Give that person your undivided attention — put your phone away — no matter what generation.”

Durand reframes “hard conversations” as “important conversations to protect and repair relationships.”

When you are struggling to see the younger (or older) generation’s perspective, Durand sees this as a great chance to ask more questions to better understand the way they look at things. However, she emphasizes the importance of being sincere. “If you aren’t genuinely curious, the listener will pick up on your lack of care, your doubt or your sarcasm and resist right away.

“Great conversations can sound like ‘Wow, we feel differently about this. Help me understand your perspective and I’ll try to share mine’ or ‘I think I’m missing something, say more.’”

If you’re anxious about the conversation, Durand suggests writing out your words in a script of what you would like to say. “Tell the person, ‘I want to say this well and I am worried about misspeaking, so I wrote it out, so I don’t mess it up.’”

Durand also recommends picking a time of day when you know you are both likely to be well rested and “at your best.” Don’t start a conversation late at night when you are tired or when you are busy with the harvest.

Pronschinske makes it a habit to respect a person’s preferred method of communication. She asks: “How do you want to be communicated with? Do you prefer text, email or phone and what time of day do you prefer?”

In Pronschinske’s opinion, the world could use more empathy. “Put yourself in the other person’s shoes.” Her suggestion is to try to build rapport and trust. “What kind of day are they having? What are they bringing to the workplace?”

Durand agrees that attempting to step into the shoes of any person you are speaking with is a good habit. But she cautions that it’s important to realize that in some cases “we may not be able to understand their experience or perspective.”

While individuals who grew up in the same time period (and place) can have a lot in common, Pronschinske cautions that stereotyping is dangerous. “Don’t put any generation in a box,” she says.

Resources

- The Future Leader: The Successor’s Guide to Family Business Leadership, a book by Patti Durand

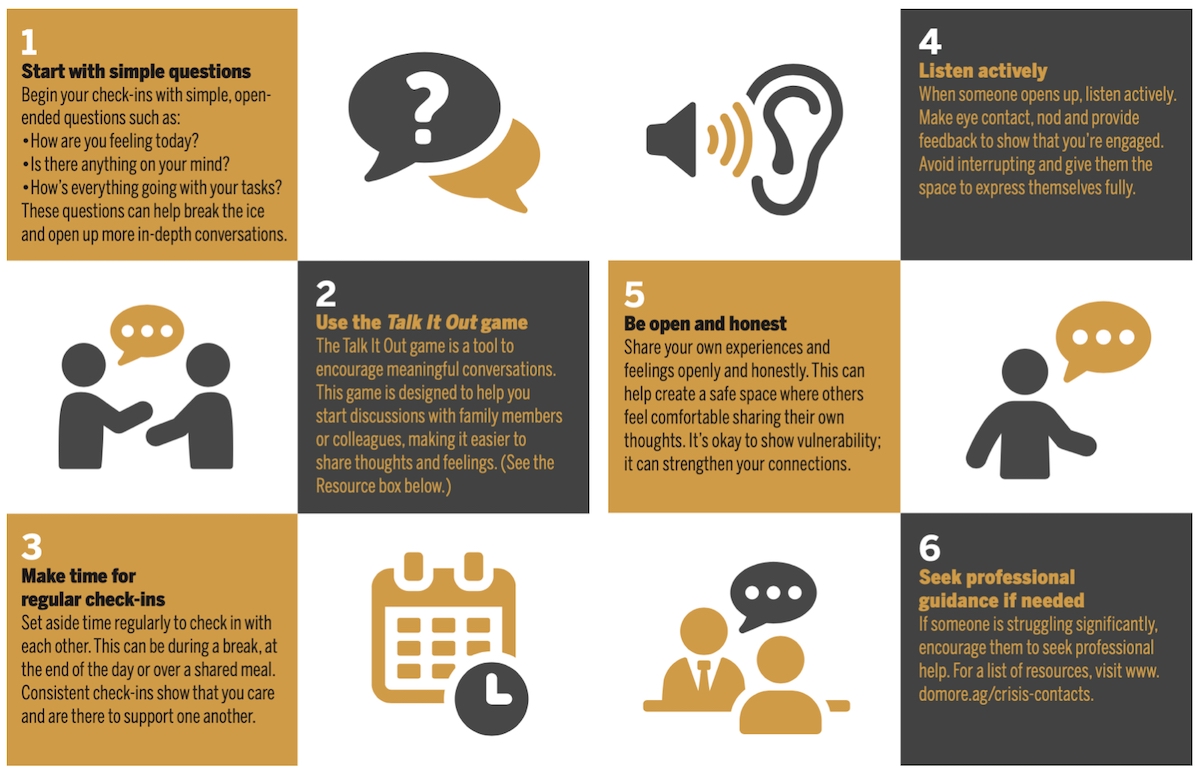

- Talk it Out – Conversation starter game from Do More Ag

- The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, a book by Jonathan Haidt

- Books by Brené Brown, a social science professor from the University of Houston. For a guide on where to start if you are new to her work on courage, vulnerability, shame and empathy