It’s their legal right under the Canada Grain Act — if farmers don’t like the grade their elevator manager offers, they can appeal to the Canadian Grain Commission for an official ruling.

But not many do.

“In 35 years of buying grain, I’ve only had it once or twice with guys that I’ve dealt with,” agrees Pro Com Marketing’s Brian Wittal. “And I know over the last 12 years I’ve been advising producers on marketing, I haven’t had anybody that’s utilized that.”

The overall numbers aren’t much different. “The CGC does on average 204 ‘Subject to Inspector Grade and Dockage inspections’ each year,” says Daryl Beswitherick, the CGC’s program manager of quality assurance standards and reinspection.

Preferring to avoid rocking the boat with their elevator manager, farmers are much more likely to shop their grain around than officially appeal a decision.

Farmers who visit CGC booths at ag shows typically understand they have a right to request re-inspection, but not all realize this right only exists at primary elevators, notes CGC community relations officer John Sawicz.

Read Also

Agronomists share tips for evaluating new crop products and tech: Pt. 3

With new products, new production practices and new technology converging on the agriculture industry at a frenetic pace in recent…

“As well, it’s not always understood they can challenge moisture and dockage, despite the fact they are well aware they can challenge grade and protein,” says Sawicz.

The procedure

Anyone who disagrees with the assessment of grade, dockage, moisture or protein at a licensed primary elevator can ask that a sample be sent to the CGC for a binding decision.

The CGC says producers should state at the time of their delivery that they disagree with the grade or quality factors assessed, and ask the operator to send a representative sample of their grain to the CGC for an inspection subject to inspector’s grade and dockage.

Both the farmer and elevator operator need to agree that the sample is representative of the farmer’s entire load.

A farmer who disagrees with the CGC inspector’s results can appeal again, asking the CGC to send the sample for inspection to the chief grain inspector for Canada. That decision will be final and binding.

A full description of the resolution process can be found on the CGC’s website under “services.”

Maintaining good relations

Beswitherick says the program usually comes into play when the farmer receives a different grade than he and the elevator had initially agreed to.

“Sometimes that’s just based on it’s a different sample; once you’ve taken a pail full of what you keep, once you start delivering truckloads, the grain can start to change. It depends. Every situation is different,” Beswitherick says.

The program isn’t much used, and Beswitherick hears from producers that they’re concerned about keeping a good relationship with their elevator.

“A lot of times I do believe producers will work out the issue with their elevator to come up with an agreement that satisfies both parties. They want to maintain good working relationships. But it is there as protection and insurance for producers if they do run into problems,” Beswitherick says.

“They don’t like ticking off the elevator guys,” agrees Wittal.

He says elevator managers might be apprehensive about continuing to deal with farmers who’ve used the appeal process in the past.”

Wittal adds that elevators might also try to discourage farmers from appealing to the CGC.

“The biggest thing is, a lot of times, the elevator tells him, ‘If you have a problem, you’ve got to let us know before we put it in our bin… if we send in a sample and then it comes back, if as the elevator company we don’t like or agree with it, or we don’t want to take that risk of having to buy it at that grade, we can’t give the grain back to you because we’ve comingled it,’” Wittal says. “As soon as they have that conversation, then the farmer says, ‘to hell with it, forget about it.’”

Shopping around

Producers are much more likely to take their samples to several elevators.

Ag-Chieve analyst Frank Letkeman says that in his 30-plus years on the elevator side of the grain industry, farmers don’t just easily accept grades they’re given.

“They will shop their grain around. It’s not like they’re just going to take the first offer that comes around, whether it’s a fair one or not.”

He says farmers are willing to drive the extra miles, especially if it means picking up a higher grade.

“I would say 95 per cent of the grain that was produced on our farm once went to our local wheat pool elevator, but now, in the new environment, we sell to four or five different buyers,” says Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission chair Bill Gehl.

Letkeman says that with the demise of the Canadian Wheat Board monopoly, there’s more shopping around, even though there are fewer elevators farther apart on the Prairies.

“There’s lots of freedom in the system right now, and that bodes well to the farmer getting a good deal.”

Wet year premiums

Wittal adds that some farmers may also wish to avoid the risk of receiving a CGC grade that’s lower than the one the elevator offered.

In a wet year like this one where grade and quality could vary widely, grain marketing consultants are urging their clients to widen the scope of elevators with whom they deal.

This year in particular, a farmer could receive a better grade from the elevator than what the CGC would offer in an appeal, getting his No. 3 bought as No. 2 because of, say, high protein.

“On red spring wheat, it may have really good protein and they can use that protein to blend off, so they may over grade you just to make sure that they get that grain,” explains Letkeman. “The different quality aspects of an individual sample may have value beyond the grade.”

Phoning around different elevators to learn what they’re looking for can really pay off this year. It helps confirm that what looks like a good deal really is a good one, as a farmer could receive a lower grade at a different location but a better price.

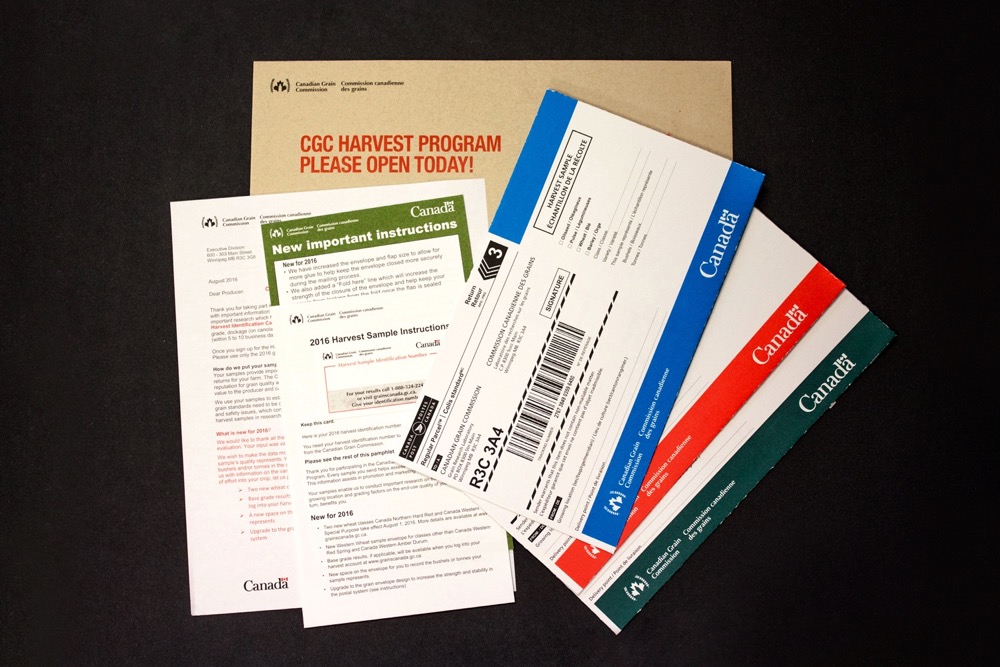

Harvest Sample Program

And to best prepare for negotiating with the elevators, consultants encourage producers to use the CGC’s Harvest Sample Program.

“It’s free, you just send all your samples in, and they’ll send you back an unofficial grade and dockage on your grains, and that gives you somewhat of an idea of what the quality of your grain is, so that when you go and talk to the elevators, you can see who’s going to give you the best deal for what you have based on your protein, moisture, etc.,” says Wittal.

CGC’s Beswitherick says the Harvest Sample Program is far more heavily used than the appeal, to the tune of roughly 8,000 to 10,000 samples a year. And a more challenging year like this one typically results in even more samples.

“It’s really important to have a very solid understanding of what you actually have and then maximize your ability to get as much as you can for what you produce,” says Gehl.