A quick scan of the farm press this spring might have been enough to convince you Canadian barley has a yield problem. The sharp drop in Prairie acreage suggests farmers may think the same thing — only 6.2 million acres were seeded last year, about two million less than 10 years earlier and half the acreage of 20 years ago.

But while barley yields were low in 2017 and in 2018, breeders say those numbers are misleading.

“It has nothing to do with varieties,” says Aaron Beattie, head barley breeder at the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre (CDC). “It’s entirely due to the environmental conditions we’ve been experiencing. That same trend was happening across all crops — most yields were down across the Prairies.”

Read Also

Agronomists share tips for evaluating new crop products and tech: Pt. 3

With new products, new production practices and new technology converging on the agriculture industry at a frenetic pace in recent…

Beattie says barley yields are up one to two per cent per year, comparable to other crops.

CDC Copeland has the highest acreage in Western Canada, followed by AC Metcalfe, which is over two decades old, says Jill McDonald of SaskBarley, the provincial agency promoting the crop.

She says even these two varieties have seen slight annual yield increases over the last 15 years due to good agronomic practices and other factors, but newer varieties released since 2012 show “quite significant” yield gains.

Canadian barley breeding is highly collaborative. Beattie works closely with researchers heading Western Canada’s other two programs — Ana Badea, barley breeding lead at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Brandon Research and Development Centre and Flavio Capettini, head of research at Alberta’s Field Crop Development Centre. The programs exchange breeding material and yield trial data.

Beattie’s program focuses about 75 per cent of its resources on two-row malting barley, with the other 25 per cent going mainly into forage and feed barley and a smaller amount on hulless barley for food and malting.

Badea’s program shows a similar breakdown, with about 90 per cent of its resources going to two-row malting barley and about 10 per cent going to two-row hulless barley for food, with some attention to two-row feed.

AAC Synergy, one of the newest varieties to come out of the Brandon program, showed yield increases of more than 13 per cent compared to Metcalfe in co-operative registration trial evaluations.

End-user acceptance

McDonald says malting barley producers are happy to grow newer, higher-yielding varieties, but there are barriers to new variety acceptance. One important factor is taste — maltsters and brewers want to maintain their beers’ flavour profiles. “New varieties have to perform well in the malting house and then for the brewers and meet their performance requirements. It’s not one specific end-user that’s holding up variety acceptance. It has to be a joint effort.”

SaskBarley and Alberta Barley have formed an informal working group to address this issue, says McDonald. “We’re trying to come up with a way to formalize a variety-acceptance strategy within the industry, and also to ensure collaboration and communication in the barley industry in Canada.”

Beattie says the craft brewing industry has already shown a strong interest in new varieties

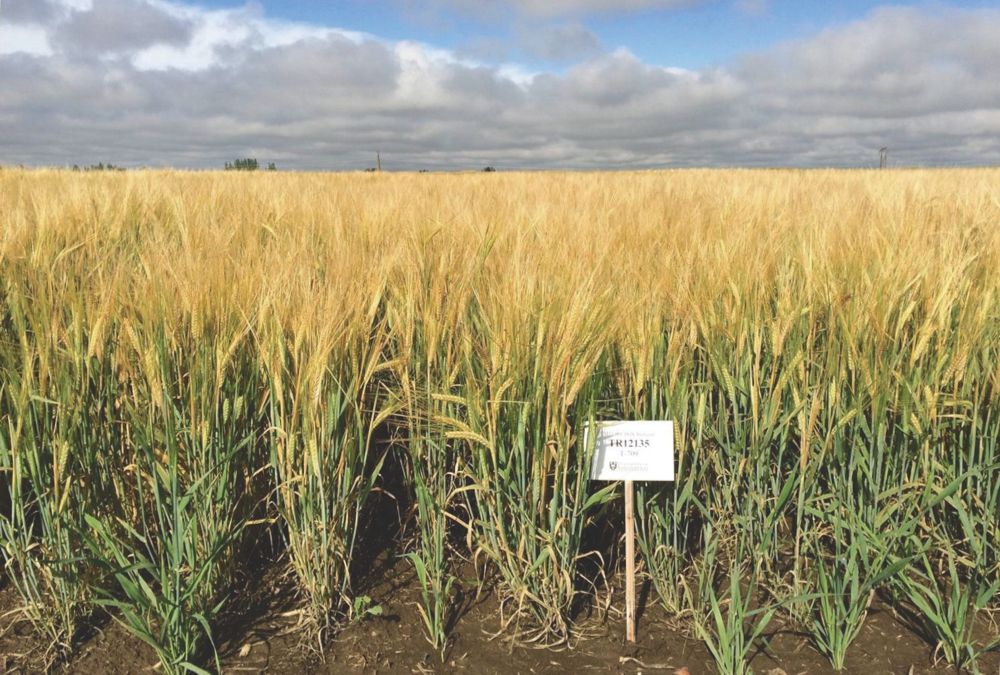

In 2015, his program released CDC Bow, which outyielded Metcalfe by 11 per cent in Saskatchewan Variety Performance Group testing, and shows good lodging resistance. The variety was received with enthusiasm by Saskatchewan craft brewers last year.

Beattie is even more excited about CDC Fraser, which he says has also been well-received by maltsters and is more in line with export market requirements for maximizing alcohol production.

“CDC Fraser has the best chance to replace Metcalfe with our export market,” says Beattie. “Fraser has a big yield jump, better than Bow, with a good disease-resistance package, including for fusarium head blight. This is the one that may occupy significant acres in Western Canada.”

Breeding for quality

Quality is another huge consideration when breeding malting barley, and this is where it gets complicated.

Beattie says that just as with bread wheat, new varieties must maintain an extremely large number of quality traits to fit end-user requirements.

“There are at least a dozen traits that impact those users — everything from grain protein content and germination energy to barley’s ability to break down starch, and the amount of beta-glucan in barley cell walls.” (Too much beta-glucan slows the brewing process.)

Breeders also look at free amino nitrogen content — the amount of nitrogen compounds that can be metabolized by yeast during fermentation.

In addition to meeting quality parameters, barley breeders have to match or exceed existing varieties’ disease-resistance profiles.

“When you work with a crop over a century of breeding, it gets harder and harder to make progress, because early on in the breeding life of a crop you make big gains and over time it gets harder to make improvements,” says Beattie. “Every time you improve these traits, it slows down the next round of progress.”

Canada’s barley breeders network with programs across Europe as well as Japan in order to access interesting germplasm and bring quality traits into local varieties.

“Because European germplasm is grown under high moisture and high inputs, they tend to breed plants with better straw strength or lodging resistance than we have here. That’s a benefit to us because that’s been a shortcoming for our Canadian barley varieties — they lodge more than you’d see in other crops in Western Canada,” says Beattie.

If barley is lying on the ground close to harvest, Beattie explains, you’ll get a higher chance of FHB, and heads may start to sprout, which ruins malt quality and slows harvest.

“We’ve noticed with some of the newer varieties that at times farmers are choosing lodging resistance over yield — they don’t want something that yields poorly, but if they have a choice between good lodging resistance and five per cent poorer yield, they may choose the one with strong straw.”

Badea says quality is important locally but also for export markets. “This is why Canadian malting barley buyers are paying a higher price. We cannot move the target for quality in a different direction — we have to stick to high standards, even if this means slower gains in yield.”

With newer, better varieties in the pipeline, all that remains is industry acceptance.

McDonald says Canada’s export market determines which varieties are accepted by our largest customers in the U.S.

“Our domestic market can’t move ahead of our export customers, and our export customers can’t move ahead of our domestic industry,” McDonald says. “Our informal working group is a positive step because we have really good communication between all levels of the value chain. I would say we are at a better spot for variety transition than we have been over the past 10 years. I think all the levels in the value chain are recognizing that we need to move varieties.”