For several years now, there have been questions about adding crops to the Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO). Beyond the charter commodities of corn, wheat and soybeans, for instance, there have been murmurs about bringing in edible beans. But early this past July, it was farmers who grow oats and barley who became the latest to join the GFO umbrella.

It’s a move that promises to do as much for research, development and advocacy as it will for exploring new markets.

It’s already getting called a big step for oat and barley growers in Ontario, particularly after the disbanding of the Oat and Barley Council of Ontario. Formed in 2001, OBCO began with high hopes, but its membership was voluntary and there was little or no funding to pursue the group’s mandate, which initially was to represent the value chain for the two cereals.

Growers, seed company representatives, elevators and processors were united under OBCO, and until 2010, the group attempted to secure funding for new variety development and also for investigating new and emerging markets.

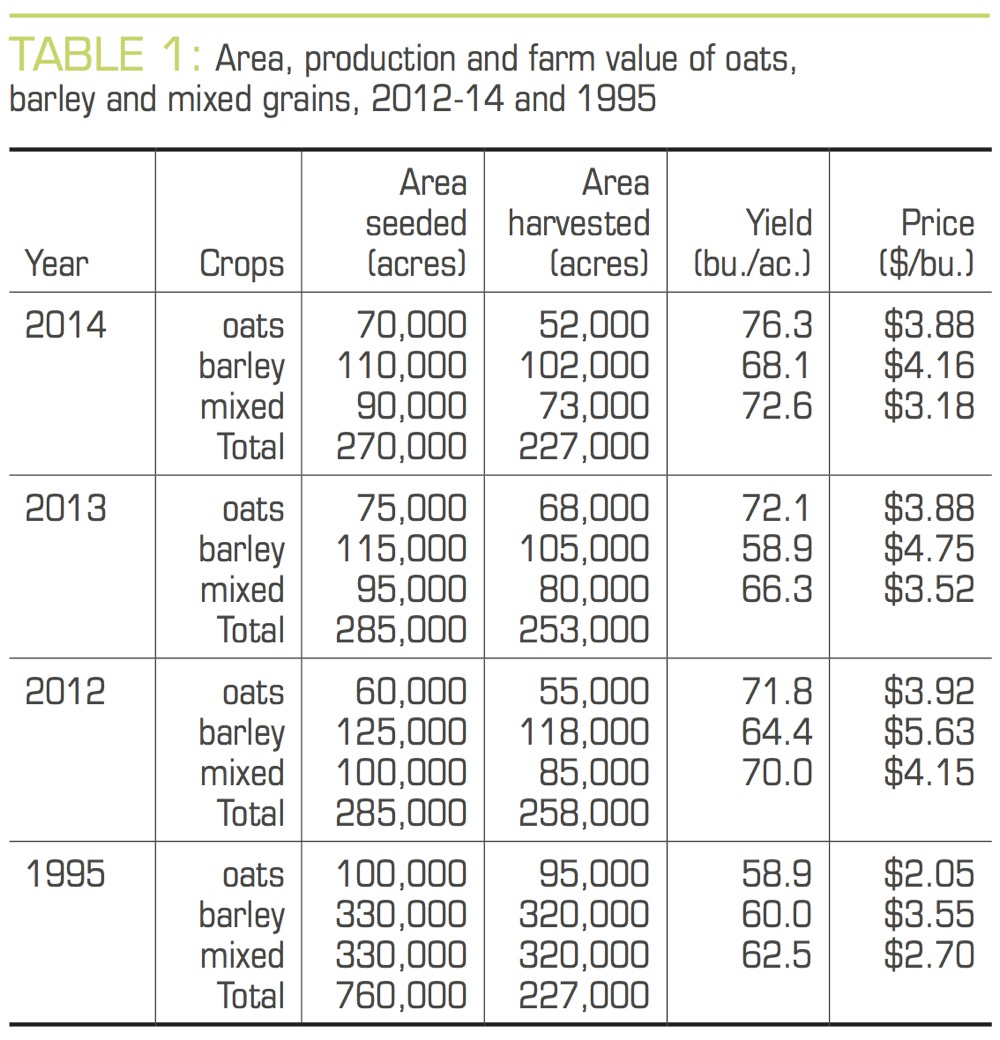

It’s been a difficult run for oats, barley and mixed grains, particularly in the past 20 years. As recently as 1995, farmers planted more than 700,000 acres of the three crops in Ontario, but barley and mixed grains in particular have witnessed steep declines (see Table 1).

There has been some good news at the same time, however. Yields are trending upwards, with oat yields up nearly 30 per cent over 1995 levels, and prices also trending higher, generally speaking (i.e. oat prices are up 89 per cent compared to 1995).

That has many in the spring grains trade enthused with the announcement that oats and barley will become the next crops covered by the GFO. It’s viewed as an opportunity to secure current market value chains and explore the development of new markets and possibly new uses. Those are all aspects that Craig Martin of Cribit Seeds and Wintermar Farms near Waterloo, Ont., is happy to see.

“We’ve been working on this on and off for several years,” Martin says. “When OBCO was not able to get funding to keep it going, we tried to keep the name going out there. Ultimately, those of us who were with the council felt that the right fit was with the GFO, but the time we lost our funding was about the same time they were trying to get their three crops to work together. And we believed then it was best to sit on the sidelines and wait and let that process get through and get settled in before we throw some other crops into the dynamic.”

Read Also

Agronomists share tips for evaluating new crop products and tech: Pt. 3

With new products, new production practices and new technology converging on the agriculture industry at a frenetic pace in recent…

Without the stability of the GFO, a lot of energy was spent on getting small-project funding from various sources. But now with the backing of the farmer organization, energies can be more efficiently directed at a stable, longer-term effort.

Pricing on the commodities themselves will remain unaffected but growers will notice the check-offs on their sales this year. Although that might be a contentious issue for some, Martin concedes it’s part of the process of belonging to such a large and involved organization. In its July 6, 2015 announcement regarding the addition of oats and barley, the GFO set its checkoff at $1.30 per tonne for barley, $1.65 per tonne for oats and the same $1.65 for oat and barley mixes.

“The GFO will not have direct marketing powers over oats and barley — it’s more like the arrangement with corn and soybeans,” says Martin. “But with oats and barley, it is kind of a loose IP program. It’s also smaller-acreage blocks where you don’t have hundreds and hundreds of acres.”

But what could be viewed as short-term pain could lead to longer-term gain, as the checkoffs are pooled and spent on research and development, new markets, and something the GFO does very well —telling the world about Ontario agriculture.

“Given the enthusiasm of the GFO staff, I think we’re going to see some change,” says Martin, adding that the first challenge might be in how that change is measured. “With their connections, a lot of what we’ll do is a matter of not wanting to reinvent the wheel.”

Learning from corn and soybeans

The biggest challenge from Martin’s perspective is to grow the oat and barley sector in an orderly fashion. If growth is too fast, the pricing will falter. If it’s too slow, market development may stumble. He believes the sector needs to continue pushing yields higher and improving the economics for growing the two cereals. Then market demand has to be carefully moved in concert with the supply.

“If we can get the agronomy there — and grow the agronomy side of it — we’re geographically well positioned here in Ontario,” says Martin. “There’s a lot of processing done in the eastern U.S. where the pet food industry and oat-milling industry are located, and from a transportation and logistics position, we’re far better positioned than dragging it in from the West.”

Northern opportunities too

As an agronomist with Co-op Regionale de Nipissing-Sudbury, in the Temiskaming area, Terry Phillips has done his own work with oats and barley in the region, including top dressing nitrogen on oats as well as adapting western Canadian oat varieties, such as Morrison, for Ontario conditions. He’s excited to know that the GFO will have a hand in stabilizing funding and providing some much-needed direction and focus on research and development.

“It’ll be good for us (in the Near North) because those are bread-and-butter crops for us,” says Phillips. “Other than plant breeding at ECORC (Eastern Cereals and Oilseeds Research Centre, part of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Ottawa station), nobody’s done anything agronomic to oats and barley for years, other than some of the fungicide work that the companies have done.”

Phillips was also actively involved with OBCO during the days when it was trying to forge a new direction for growers. In the early days of the council, there was a drive to get malting barley established in parts of Ontario, particularly in Temiskaming, but still closer to the brewing centres of Montreal and Toronto. At that time, there were issues concerning protein levels and other agronomic factors, but the larger challenge to getting malting barley established was with growing consistent volumes.

“Nobody’s been playing with these crops,” says Phillips, adding that Peter Johnson, former provincial cereal specialist, once jokingly stated that oats is the last of the cultivated weeds. “But with the freight issues of Western Canada, and oats being low in priority for preferred freight for rail transportation, we have a really good opportunity in Eastern Canada. Quaker is still here and it’s still looking at its proprietary oat program and has good buy-in in Ontario, including Temiskiming. It’s like an IP cereal program.”

Industry sources also say that Molson is looking to secure more Ontario-grown barley. And Phillips cites one individual in 2014 who talked of a major malting barley buyer centred in Barrie. In that discussion, such a buyer was involved in filling malting demands based on volumes from a 15,000-acre block.

“We’re not going to see the big players investing in oats and barley — it’s too small a market crop for them,” says Martin. “But as a small player, working with the GFO with its connections and influence, it’s going to be a whole lot more effective than we can be by ourselves.”