Like farmers everywhere, soybean growers are big fans of big yield numbers. The more bushels, the better, and now, with yields commonly into the 70s, some even talk of reaching the century mark in just a few years’ time.

That quest is leading growers down a few unexpected roads, such as applying nitrogen to soybeans.

It seems counterintuitive. After all, one of the great competitive advantages of soybeans is their ability to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere. But N fertilization is also an idea with a lot of sticking power.

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

Horst Bohner, the Ontario agriculture ministry’s soybean specialist, has seen N research in soybeans back to the 1980s and 1990s, and he has conducted dozens of his own trials and test plots since 2004.

His experience seems clear. Under normal growing conditions, Bohner says, he has yet to see extra N pay for itself, let alone elevate yields closer to that 100 bu./ac. level. The only cases where he’s seen a significant impact have been in soils where N levels were extremely low, or in crops with damaged roots.

Even so, Bohner still believes it’s worth discussing the idea, particularly with the emphasis now on driving soybean yields into the 80s and 90s.

The problem comes in comparing growing conditions in Ontario with those in the U.S. where much of the research has been done, and where irrigation is more common and soil profiles are enviously deep.

“In those fields, there is a lot of available nitrogen in the soil, so it all comes together typically in the soil,” says Bohner, who, with Dave Hooker at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown Campus, has looked closely at the results. “Anything that can be done to improve soil health, including crop rotation, is a positive thing for soybean yields. But nitrogen specifically… there’s not much of a link.”

From the Grainews website: Soybeans in Saskatchewan

Nature’s way

As with other legumes, a soybean plant derives nitrogen from a symbiotic relationship with rhizobial bacteria, which “fix” atmospheric N2 (nitrogen gas) into NH4 (ammonium). In that form, it’s more readily available for uptake into the plant.

But fixation doesn’t account for all the nitrogen in a mature plan. Instead, some 40 to 70 per cent comes from the soil.

It’s a number that might make you think that a nitrogen application would boost yields, yet in a series of research studies — from South Dakota and Iowa to Minnesota and Ontario — there has been little or no yield response to straight nitrogen applications.

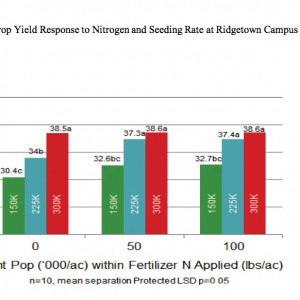

One study that Bohner uses to emphasize this point is from 2012 at Ridgetown. In a project that sought to define timing and seeding rates for double-cropping soybeans, one of the results confirmed that high seeding rates outperformed lower seeding rates, but that in a low seed-rate environment, 50 lbs. of N per acre applied at planting outyielded the zero-nitrogen plots.

Yet at higher application rates, even up to 100 lbs. of N per acre, there was no significant yield compared to the 50-lb. rate (Figure 1).

The physiological cost

“The soybean plant will use the nitrogen that’s the cheapest in terms of physiological cost,” says Bohner. “Fixing nitrogen from the air is quite costly to the plant because it has to feed those bacteria and the nodules, so when it has what I’ll call free nitrogen available in the soil, readily available to the plant, it’s not going to fix nitrogen.”

If there was a way to get the soybean plant to do both at the same time — fix nitrogen and use the nitrogen fertilizer — then 100 bu./ac. yields would be much easier to attain. And, in fact, attempts are being made through the use of slow-release nitrogen or other growth promoters, but thus far, the yields haven’t grown substantially, Bohner says.

The bottom line is, in the presence of high N-rate applications, nodulation is inhibited because the soybean plant will nodulate only when it needs N.

“With respect to nitrogen, not only can we not show an economic response, we can’t even show a yield response,” Bohner says. “It’s ridiculous how the plant refuses to respond to nitrogen fertilizer.”

“We’ve tested various sources, we’ve tested various placements and we’ve tested different timings under every different scenario,” adds Bohner, noting that he started the N trials in 2004 and has kept them going through 2013. “So far, it’s been a complete failure in every case to make money for producers.”

Why keep trying?

Eric Richter, agronomic sales representative for Syngenta Canada, agrees with Bohner’s assessment of N-applications on soybeans. On one hand, he has seen results over the years where growers apply higher amounts of nitrogen with little or no response. On the other hand, he’s also seen growers with 35-bu./ac. yields on good loamy soils, relatively new to soybeans, jump to 50 or 60 bu./ac. with the simple addition of an inoculant.

From Richter’s perspective, phosphorus and calcium are also important in driving soybean yields. But the real key to improved soybean yields comes in a root system that will help push podfill later in the season.

“It’s the period in which the most significant amount of nitrogen and phosphorus — and potassium, for that matter — is taken up,” says Richter, adding that corn, by contrast, builds its yield in the front half of its life cycle. “In soybeans, as we move towards these 60- and 70- and 80- and 100-bushel yields, we’re asking more of these plants at a time when the root systems are actually getting tired. To go beyond 60 to 80 bu./ac., we have to figure out how to get enough nutrients into the plant at the back end… I’m not saying I have the answer.”

Another similar strategy that he’s noticed is that growers with poultry manure tend to have better yields. In fact, those producers usually have pretty impressive corn yields as well.

“I’m assuming those growers have the same management skills and roughly the same soil types, but if you compare apples to apples, the one set of growers that really come up above the rest are the ones who have access to poultry manure,” says Richter. “There’s something that really lines up with the nutrient-uptake pattern for soybeans.”

In the U.S., growers can borrow from the pages of elite growers such as Kip Cullers, who advocates multiple nutrient treatments, or Marion Chalmers, who has worked with reduced plant populations. Richter acknowledges that U.S. growers manage their farms and crops under a different set of conditions, including irrigation and a soil profile that most Canadian growers can only dream of. Yet somewhere in those approaches, there’s a guideline for growers on this side of the border. And it’s a tricky balancing act, according to Richter.

“My belief is that as we increase fertility in healthy soils, we have to decrease populations, but we still have to have an optimum stand,” Richter says. “If we get too high population and too much fertilizer up front, then we generate no response. I’m a big fan of the approach that as we increase fertility and increase soil health, there’s a huge opportunity to lower seeding rates and increase yield. That’s why I’m so excited about variable-rate technology in soybeans.”