Auto steer and real-time kinematics (RTK) that allow an operator to repeatedly get within millimetres of a target are, to me, the most obvious investment that you could make to improve the efficiency of mechanical weed control practices like inter-row cultivation. Operator fatigue and accidental damage to the crop would be greatly reduced by integrating this technology with tillage implements.

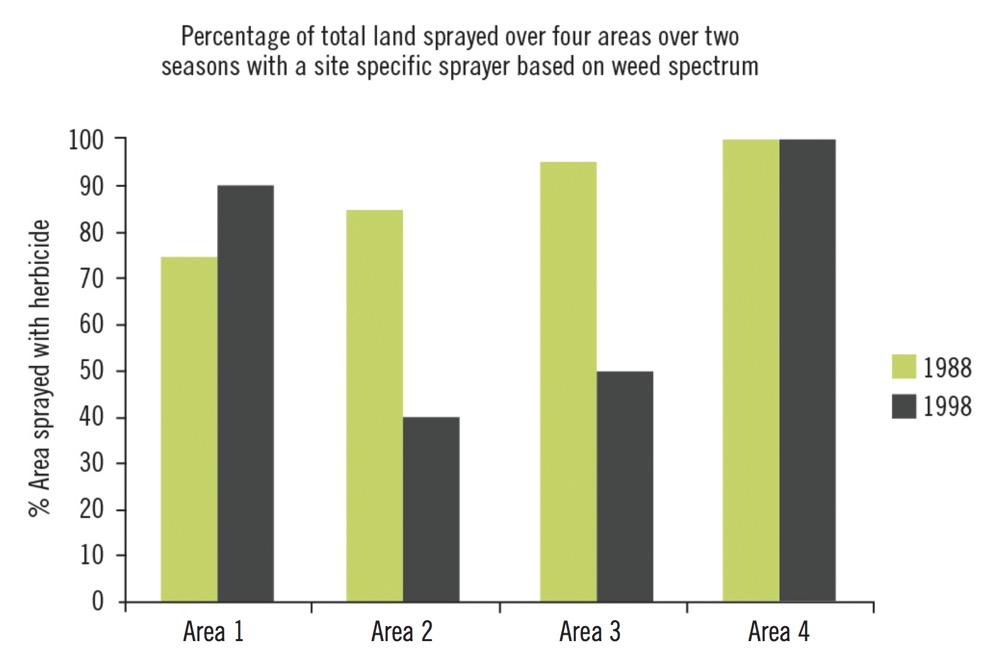

When I started my graduate studies at the University of Guelph, I did some field work for Heather Griffiths, who was working with the School of Engineering to evaluate a site-specific sprayer in Ontario field crops. The idea was that a sprayer would only apply herbicide where there were weeds. In Griffiths’ study, she observed a 59 per cent reduction in the area sprayed with a herbicide. Unfortunately this was only in one treatment area of one site. The other treatment areas and research sites either saw modest reductions in the area sprayed, or the entire field had to be sprayed because it was covered in weeds (Figure 1 at top).

Simply put, the majority of annual weed species takes up a pretty uniform portion of most fields (Figure 2 below) and there is little opportunity to shut a sprayer off for lack of weeds.

However, an opportunity does exist due to the way perennial weeds like field horsetail are distributed (Figure 3 below), since they are patchy and don’t move around much from year to year.

Let’s assume we had field horsetail in glyphosate-tolerant corn. You’ll likely need to do a broadcast application of glyphosate to control most annual weed species, but what if you could inject another herbicide which was effective on field horsetail, like MCPA or Broadstrike RC, whenever the sprayer detected the patches of field horsetail? Now we have something that would make a lot of sense provided we could develop the maps easily and cost efficiently.

Right now, that’s the challenge. When Griffiths did her work in the late 1990s, the effort to get an accurate map was pretty labour intensive and costly. Remote sensing tools like near-infrared (NIR) and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) are newer tools that have made the process of weed mapping more cost efficient, although getting these tools to efficiently and accurately separate weeds from crops is still just out of reach. But it’s much closer now than it was in 1999.

Read Also

Agronomists share tips for evaluating new crop products and tech: Pt. 3

With new products, new production practices and new technology converging on the agriculture industry at a frenetic pace in recent…

Have a question you want answered?Hashtag #PestPatrol on Twitter to @cowbrough or email Mike at [email protected].