The debate over biotechnology is evolving as new voices enter the debate, technology changes and much of the innovation in the field is coming from outside of North America.

That means that some of the scientists that have defended the use of genetically modified crops over the past decade have to deal less with activists with intractable opinions and more with people with curiosity or worry about their food.

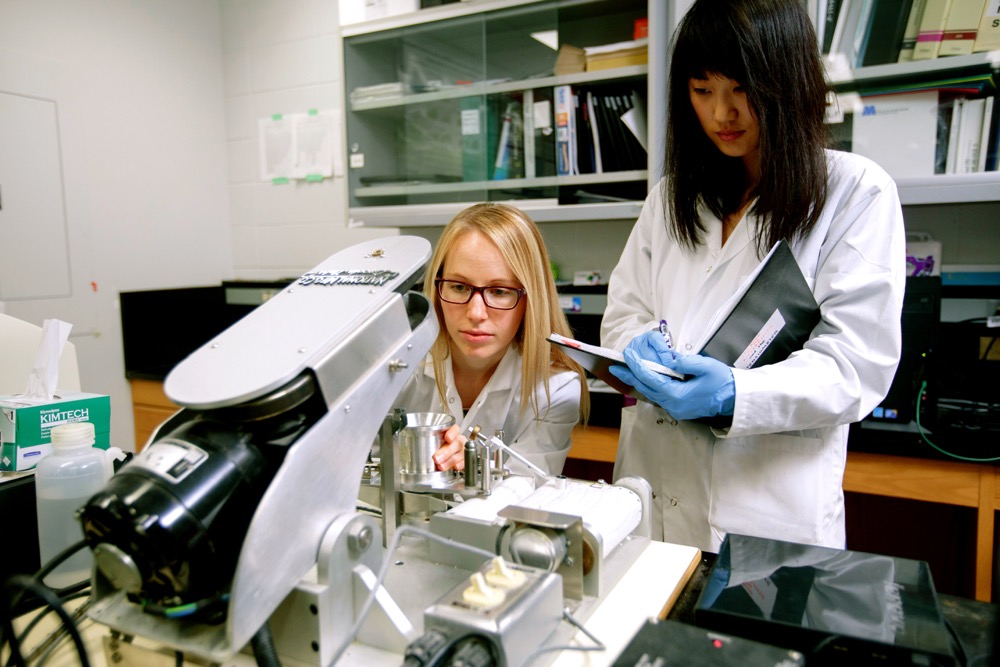

Scientists from around the world, and some representatives of farm organizations gathered in Guelph recently to learn about communication relating to agriculture technology and to share their stories of being on the frontline of the debate.

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

“It’s funny, I think we’ve turned a corner,” says Dr. Kevin Folta, a professor at the University of Florida, and perhaps the most-well-known of the biotech defenders. He says activists are changing their focus from safety of genetically engineered crops to herbicides and bees.

“What’s changed is that the average science enthusiast is excited about technology. They love a new phone, love enhanced features in their car and now they’re a little excited about technology that makes their food safer or healthier. The nerd brigade has turned their attention to it. In social media, they have taken our place. It’s no longer four scientists talking to the unreachable.”

Scientists are trained to think and communicate logically and through the scientific method. But people need to know you care and are listening before they listen to facts and logic. That’s the hard lesson the industry has learned, but conferences like the Biotech Bootcamp bring together scientists to learn to speak a new language.

“We’re doing amazingly better,” says Folta, who has received threats online and offline, and continues not to open packages whose origins he does not know. “Scientists listen to debate and poke holes in arguments. We didn’t listen to understand people. The corollary to that is when we listen and understand why people are upset and have concerns, we realize this is their reality in their heart. We can’t ignore that and always did.”

The use of the technology is spreading, says Dr. C.S. Prakash, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Tuskegee University, with applications that have more consumer impact. People post pictures on Instagram of a genetically engineered grapefruit because it is a brilliant colour and higher in antioxidants, not because it is genetically engineered, he says.

“There are more products labelled boldly as having genetically engineered ingredients,” he says. “And it’s not driving people away.”

For the first 25 years of genetically engineered crops, the vast majority of use centred around corn, soybeans and cotton. Now, there are genetically engineered fruits and vegetables being developed around the world, mostly focused on disease resistance or consumer health.

Disease resistance is the area where genetic engineering has the biggest potential to do good, says Dr. Alison Van Eenennaam, of the University of California – Davis, who runs a livestock genetics research lab there. But she says too many good solutions are sitting on shelves at land grant universities and not being used.

The technology is also changing with more focus being placed on the recently developed gene editing techniques. Folta says this technique should be more acceptable to consumers and it is easier for them to wrap their head around.

Genetic engineering techniques are now widespread and move quickly around the world. African governments are solving their own problems using genetic engineering, says Prakash, something reiterated by Folta.

“They have beautiful labs in Kenya,” says Folta. “They are going to solve their own problems. It’s not coming from us. They are sick of waiting.”