In precision agriculture, the focus is typically on the low-hanging fruit, i.e. the use of yield data to create variable-rate fertilizer scripts, investing in individual row units with automatic down-force, or using aerial imagery to pinpoint trouble spots in a field.

Most such discussions are also confined to choices about soil, seed and fertility. Yet the main limiting factor in any farm sector is the weather. And it remains uncontrollable.

So, what if moisture could be controlled, or at least if its impact could be minimized? What would happen to corn yields, or to soybeans or wheat, or edible beans or oats?

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

Growers in Canada have heard presentations from the likes of Frances Childs and Kip Kullers about their successes in the late 1990s and 2000s. But it’s Georgia farmer Randy Dowdy who’s recently captured farmers’ attention in driving corn yields to the 500-bushel-per-acre limit, and among other practices, he uses “fertigation,” the combination of applying fertilizer through irrigation.

So much history

It might be perceived as something new but fertigation can trace its origins to ancient Babylon and the Aztecs of Central America, where “hydroponics” was used to grow fruits, vegetables and trees in water. It underwent many different transformations, and in the early 1930s, drip irrigation was discovered in Israel, where a small puncture in a waterline near a fruit tree was found to boost yield compared to nearby trees.

From there, hydroponics was used to grow food for soldiers during the Second World War and it soon spread to different countries around the world.

Now it’s making inroads in Canada by way of the U.S. Friedhelm Hoffmann, precision ag specialist with Lakeside Grain and Feed Ltd., in Forest, Ont., is a strong proponent of fertigation, having seen it work during his time in horticulture in the past 15 years.

Hoffmann maintains that in spite of concerns about initial investments or operating costs, fertigation can be a game-changer and a money-maker on the row crop side as well. The system, he says, addresses weak spots in the field during the season, making the crop less variable and providing greater strength and integrity against diseases and pests. Fungicide protection programs are also easier to manage, further improving plant health and strength.

Through all of this, yields rise and the quality of grain (or fruit) is more consistent.

But it comes with a few provisos, including a higher demand on management skills.

“The first year, we had 280 bushels per acre on corn; we did wheat and it yielded 140 bushels per acre,” says Hoffmann. “You can raise the yields quite a bit but you have to know what you’re doing. It’s not that simple and I’m very careful in saying that because there’s a lot of management involved.”

Fertigation definitely falls within the precision ag sphere. Its capability to deliver both moisture and fertilizer in precise doses is at the heart of what defines precision ag.

The advantages are obvious, including frequency of treatments, the accuracy of feeding only what is needed, maximizing crop nutrient requirements and boosting yields, all while reducing environmental hazards such as leeching or volatilization. Its obedience to the 4R principle for fertilization is another major advantage.

Hoffmann is quick to observe that fertigation is not for everyone. In addition to the increased management demands, there is a considerable initial financial commitment (depending on the type of irrigation system used), and a grower has to decide to “man the pumps” themselves or hire someone else to do the job.

Getting started

There are numerous examples of similar technologies that have come with unsubstantiated claims. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs or “drones”) and tile drainage are the more prominent targets. When the former leapt on to the scene five to seven years ago, there were marketers whose promotional efforts hinted at the notion that a UAV would make a grower more productive just by flying it over their farm. With tile drainage, there’s the perception that “it costs too much,” yet any drainage contractor will confirm that the payback on tile drainage is enough to ease the decisions on which new piece of metal they can afford.

“Management is the limiting factor,” says Hoffmann. “When you start with row crops, you still have a lot to learn, like a starting phase. We know where it works and where it doesn’t. Do I think that it’s economically possible? Yes, it will be — eventually. You just have to work with it right away and start with a small acreage. If you can make 20 to 30 to 50 bushels more, eventually it will pay.”

Before getting started, it’s best to identify the type of irrigation system to be used, be it a conventional pivot design, a drip irrigation setup or a subsurface layout. Each has its associated costs as an outlay: pivots may be easier to operate in terms of “walk-away” simplicity but sufficient water supplies and a pond are necessary, costing as much as $60,000 for a drilled well and $10,000 to $15,000 for a pond.

With drip or subsurface systems, the water usage is considerably less, so initial costs are not as high. An overhead boom irrigation system is another option but it, too, requires much more management.

Hoffmann does say though that no one who invests in fertigation should be abandoned once they make the purchase. Compared to the number of growers who currently use fertigation, there are plenty of service providers and specialists around to help.

“There are all kinds of companies and services to help you to understand it,” he adds. “They might not be there to turn it on, but for all of the technology, they’ll teach you and help through all of the hoops.”

Six steps

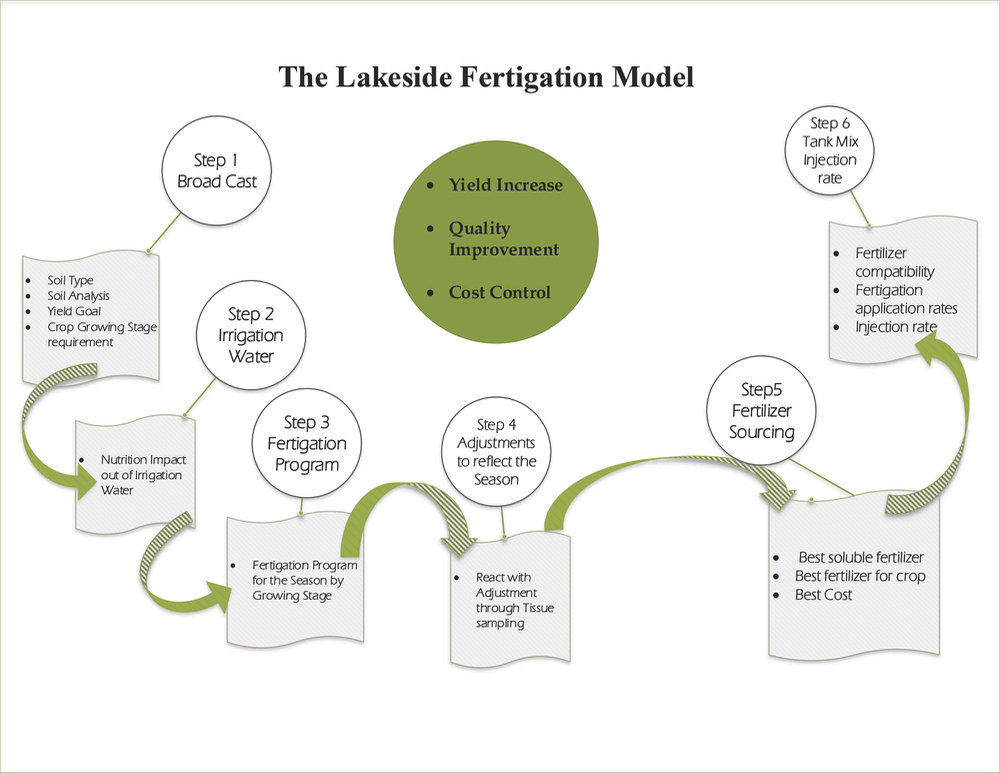

Hoffmann and the staff at Lakeside have come up with a six-step model to increase yield, improve crop quality and control costs (see below).

From Step 1 through 6, the program is set up to be interconnected yet focused on a specific stage in the fertigation system. Step 1 begins with understanding the soil, including type and analysis. Yield goals need to be established as do crop growing stages and their requirements. That has in impact on Step 2, which examines the nutrient impact of irrigation water, including water analysis to determine whether measurable levels of nutrients are present. Hoffmann notes that it’s important to account for all levels of available nutrients, whether they’re in the soil or in the water.

Steps 3 and 4 provide insight into the entire program’s goal of optimizing fertility at different stages of the growing season. In an example from a farm in Illinois, Hoffmann connects planting date and broadcast applications to assess what’s already in the soil. The program then provides detailed recommendations of various inputs and concentrations at four key intervals in the growing season: at establishment (a 45-day period), at flowering (20 days), at pod fill (25 days) and during its maturation (35 days). The goal is to adjust to specific conditions during these intervals in a growing season using tissue samples.

Steps 5 and 6 concentrate on finding the best sources of fertilizer at the most cost-effective levels and working towards determining fertigation and injection rates.

“I can sit down with the farmer and say, ‘This is roughly what you need, this is what it will cost and this is what you need to manage’,” says Hoffmann. “It’s all about the right design — it needs to fit your operation. There’s no such thing as a generic plan because our soils are different and our farms are different.”

Lakeside Grain and Feed Ltd. supports its growers by providing a full-service program with an injector, for “plug-and-play” features to make the management easier.

Challenging mindset

Hoffmann concedes that fertigation might be an easier sell with horticultural producers than row-croppers. The presence of timely rains or moisture provided via irrigation pivots can be the difference between hitting the specs on quality, quantity and consistency for a fruit and vegetable grower versus having no crop at all. For a farmer with corn, wheat and soybeans, a prolonged dry spell might result in yield losses, but as was the case with 1988 and 2012, there were still crops to harvest, in spite of brutal growing conditions.

It’s a different world in the horticultural sector where the appearance of the produce can be paramount, especially in the fresh, direct-to-consumer market. Even in processing, there are limits as to the imperfections or blemishes that are tolerated.

“That’s why irrigation is not questioned in horticulture, because you can’t take the suffering of the crop,” says Hoffmann. “Corn can suffer and you’d have fewer bushels — maybe 10 or 15 bushels less — but you just live with it. In horticulture, you can’t afford that: every management tool or thought process that can be considered has to be considered.”

That’s also why he stresses the management aspect. As much as he can suggest that sandier soils are the more responsive soils or that special attention is paid more to potash levels than even nitrogen, it’s managing the fertigation system that may not sit well with most farmers. As with any component of enhancing yields, management is the common denominator. Whether it’s no till, managing for weeds or growing crops under contract, farmers must always place a higher premium on their management skills, and some can’t see applying that added effort — for whatever reason.

“That’s the case for every process on our farms and whatever you add,” says Hoffmann. “You have to think about it and ask yourself, ‘Do I want to do that or not?’ Will you have success with it? Yes, you will have success, and of course, you will have a few things that go wrong.”

But it’s similar to no-till farming, where nothing turns itself around in a year or two. Fertigation is a long-term commitment.

Vegetable farmers are a little more dedicated on the management side, because they have to be, says Hoffmann. When testing fertitigation, they saw substantial increases in yield, with perhaps less of an add-on in terms of management. In fact, Hoffmann had one horticulture producer who became irritated with the gains he had in pepper production: he wanted 25 tonnes of peppers and he wound up with 30 tonnes.

“Bottom line, in Ontario, if you have light ground, a cation exchange capacity (CEC) up to 10 or 12, you should think about irrigation,” Hoffmann says. “And you don’t have to invest right away into everything. Subsurface or if you want to go into pivots, you can but that’s expensive. Subsurface is nice because you don’t need as much water pressure and you likely don’t need a pond. You can work with low pressure and not waste a lot of water.”