Keith Gabert rarely tells Alberta canola producers straight up not to spray fungicide as a preventive against sclerotinia stem rot. But last year, the Canola Council of Canada’s agronomy specialist for central Alberta south did just that.

“In the Drumheller area, where they don’t always have as much moisture, they’d sprayed for sclerotinia in the past and were having a hard time taking it off the list,” he says. “But in 2015 they had a drought and I told them over the phone not to spray for sclerotinia.”

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

Drumheller in 2015 was a special case. Typically, Gabert says the advice for preventive fungicide application goes by the bushel: if producers have a 35-bushel crop or better and they’re seeing canopy wetness, spraying for sclerotinia is important. “If you’ve got the weather conditions and that investment dollar to spray, I recommend it,” he says.

This year, early reports suggest there was higher-than-normal incidence of the disease in Western Canada. But the “when” and “why” of spraying preventively for sclerotinia is not a given.

The Canola Council has a risk assessment checklist for sclerotinia on its website that takes into account all three aspects of the sclerotinia “disease triangle” — the host, the pathogen and the environment.

Harder to assess

Barbara Ziesman, provincial plant disease specialist for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, says economic thresholds are much more difficult to establish for disease than for insects. “Even if pathogen levels are constant, the level of disease risk is not constant. That’s because diseases are dependent on the environment, and the risks can change over the growing season. It is fairly fluid.”

The sclerotinia checklist takes into account the producer’s rotation, disease incidence in the last host crop, environmental conditions and current crop density. The latter measures conditions in the microclimate under the canopy, as well as the yield potential, which helps producers decide if spraying will pay.

It’s not an exact science, and some producers opt to avoid any risk by spraying preventively every year. But Ziesman says this creates a new kind of risk.

“The more we apply when the risk isn’t there, the more selection pressure we’re putting on pathogen populations. Not only is it less economically efficient, it’s potentially creating more risk long term.”

Gabert suggests producers account for the cost of fungicide for sclerotinia control — between $20 and $30 per acre including application — in the winter, and figure out where that product is coming from in advance.

“I’d rather producers pencilled it in as part of their cost of production, which means they’ll be proactive about monitoring for the disease,” he says.

Blackleg control: no yield benefit

Preventive spraying for blackleg in canola is much more controversial.

For one thing, the risk of blackleg is easier to predict than sclerotinia — pathogen levels build over time in infected fields, a situation exacerbated by use of particular varieties in a field over several canola cycles.

For the most part, blackleg is managed via good genetic variety resistance, says Gabert.

“I’m sure there is a benefit to spraying for blackleg under high pressure, if you know you have blackleg issues, and you scout carefully and see some lesions on the leaves. “It’s a good tool to have in your tool box, but I’d hope it’s a tool that producers don’t need to use if they select varieties carefully.”

Gary Peng, a research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Saskatoon Research Centre, says the first line of defence against blackleg is always resistance. Variety resistance is evaluated annually and ratings are publicly accessible.

Following that, producers should assess their unique situations during harvest, and if they see more than 30 per cent disease incidence they should extend their rotation in order to lower pathogen levels.

“In some operations in southern Manitoba we see more frequent and higher disease levels, and it’s still not clear what’s going on — whether it’s special pathogen races there, or more intensive canola being grown. Most often the severe disease that we have seen in the field is following year-after-year canola,” he says.

Little benefit

Peng was the principal investigator of a team that assessed the value of fungicide for blackleg control in five plots at five locations across Western Canada from 2011 to 2014. The team analyzed whether fungicides would prove beneficial for blackleg control if genetic varietal resistance broke down.

They found early application of fungicide reduced the overall impact of blackleg when the canola cultivars lacked resistance and disease pressure was high. But the application showed little benefit to cultivars that were either moderately resistant or resistant. And they observed no yield benefit in the treated fields.

Peng says fungicides should be used only as a last resort in blackleg control. “I think it’s a good business decision to limit use to when it’s really needed, to preserve the use of the chemistry over time,” he says.

Canada’s fragile trade relationship with China when it comes to canola is another important consideration. Even though following recent trade negotiations, China says maximum dockage levels will remain at 2.5 per cent of a shipment for the time being, Peng says it’s in producers’ interests to keep disease incidence down.

“Although in a lot of cases we say fungicide application may not provide a huge yield benefit, it will help to reduce the incidence of disease and result in less contamination of the seed. That might help to alleviate our trade issue with China,” Peng says.

Saskatchewan research raises doubts about routine spraying

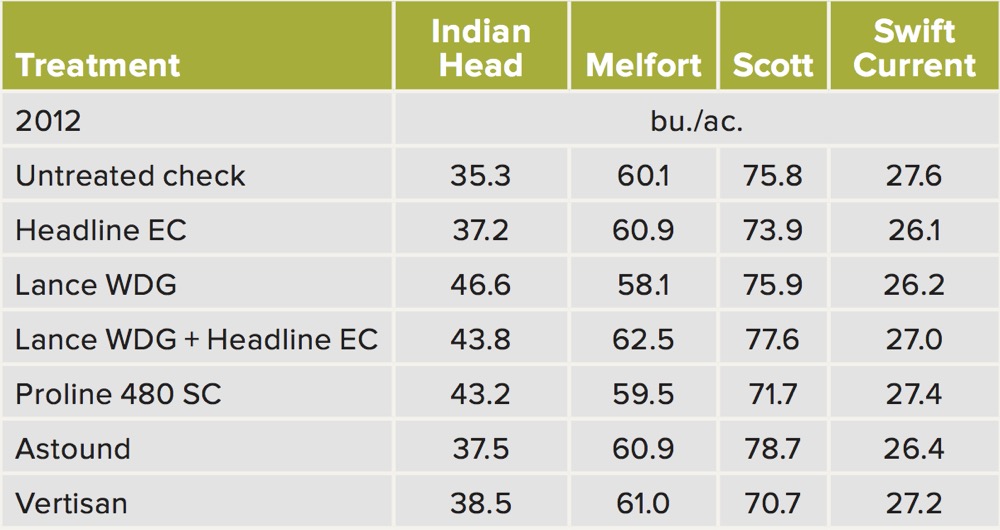

A 2012 study by AgriARM looked at the effects of fungicide treatments at four different locations in Saskatchewan. It said overall sclerotinia severity was higher at Indian Head than Melfort or Scott. At Indian Head, treatments with Lance, Lance + Headline, Proline, and Astound resulted in significantly less severity of sclerotinia than where no fungicide was applied, while there were no observed differences between treatments at Melfort or Scott (see charts at bottom).

“Treatment effects were not significantly different when averaged across sites. Within sites individually, differences among treatments were only observed at Indian Head, where treatment three (Lance) yielded higher than the untreated check,” the study said.

“The results from this demonstration confirm that fungicides are an effective measure for minimizing the impact of sclerotinia stem rot on canola yield; however, benefits may only be realized when disease severity is sufficiently high to cause significant yield reductions. Our data suggests that annual, preventive applications of foliar fungicides to control sclerotinia stem rot in canola may not be economically viable over the long term throughout much of Saskatchewan.”