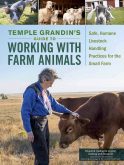

Give and Take: Why helping others drives our success

By Adam Grant, Penguin Publ.

Adam Grant’s approach to business relationships seems counterintuitive, like it would make you a suicidal little fish in a tank of big, hungry fish, but Grant sets out in his business bestseller Give and Take to prove that good guys really do finish first, eventually. Do you believe it?

Grant is no New Age self-helper. He’s an internationally respected professor of management at the prestigious Wharton School of Business, and his theory is that people approach relationships with a choice of three mindsets — to give, to take, or to match. Some of us start by asking, “how can I contribute?” Others start with, “how much can I get out of this exchange?”

Read Also

The big squeeze: How to be fair to siblings during farm succession

Managing sibling business relationships on family farms.

Most people are what Grant terms “matchers.” We expect our kindnesses to be returned, we like win-wins, and we think fairness is very important.

But then there are takers among us who try to extract as much as they can out of every situation, and there are givers, who shift their frames of reference to the recipient’s perspective.

Most of us will think we know which personality type is likely to succeed in business. We’re so sure, in fact, that we even change our own behaviour, Grant says. “Although many of us hold strong giver values, we’re often reluctant to express them at work.” Basically, we think it’s risky to seem a pushover.

Yet the book points out some unexpected twists that impact high-level business thinking. For example, takers can tend to get sucked into bad decisions, essentially throwing good money after bad because they have a harder time accepting failure and can’t hear the feedback as quickly and efficiently as givers.

Of course, Grant also has his quotable quotes. “Success doesn’t measure a human being, effort does,” he writes. Or, “Givers advance the world. Takers advance themselves and hold the world back.”

As a journalist, I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing many humble business leaders, so the chapter describing what Grant calls the pratfall effect rang very true for me. Essentially, it says that when experts or leaders act more vulnerable, they appear more human and approachable, instead of superior and distant.

At one point Grant does concede that there’s a time and place for leaders to be perceived as powerful and strong. However, he quickly adds that in teamwork situations, this approach can often deter people from contributing. Similarly, he says givers tend not to negotiate as strongly as takers and matchers, but find better solutions by seeking advice and asking questions.

Which leads to Grant’s discussion comparing doormat givers to successful ones. Once again, it’s your approach that makes all the difference. Giving without regard to your own needs causes burnout and in the end isn’t as successful. He even goes on to prove that giving without form or limitations isn’t as fulfilling.

It turns out that if you plan your giving, you can actually give more sustainably. By chunking your giving into certain time frames or confining your giving to specific causes, you actually energize your giving and be more successful with it.

He goes a step further and actually quantifies the ideal giving quotient, citing several studies showing that people who volunteered about 100 hours a year are happiest. However, it has to be a choice, not an obligation, and it has to achieve something. It’s the improvement that givers really crave.

Grant also says givers tend to be hard working and that they love to give to people with grit. Those are the folks who stand up to challenges and persistently work their way through them.

But it’s also about being thoughtful instead of too trusting or too timid. Grant says givers need the ability to screen out insincerity and to not confuse being agreeable with being genuinely kind.

It’s also true, he warns, that there’s a fine line between giving and clever matching, although the book struggles to prove any difference.

Grant concludes with outlines of several giving projects, plus websites and initiatives to create an environment of giving as well as techniques for learning how to be a better giver.

It turns out that sometimes you just have to ask and people will give.

His book is an enjoyable easy read, maybe blurring the lines between how community and individuals operate, and between social science and business. But (I know there’s a joke in here somewhere) this book would be a great gift for Christmas.

It’s the message of the season, but told with business attitude. “If you spend the money on yourself, your happiness doesn’t change,” Grant tells us. “But if you spend the money on others, you actually report becoming significantly happier.”