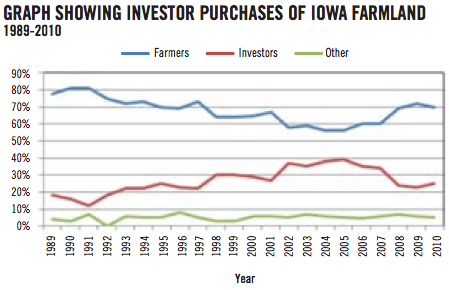

Owning farmland is no longer a passion restricted to farmers. Today it is just as likely that farmland offered for sale will be bought by an individual investor, a developer, an investment fund, or even a sovereign wealth fund.

While this demand is a boon to land values and those farmers seeking to sell land, it has also driven prices well beyond the land’s agricultural productive value, frustrating both those trying to get into farming as well as farmers seeking to expand.

But high land prices aren’t the only reason farmers are concerned about selling farmland to non-farmers.

Read Also

The Secret Sauce of Sibling Run Farms

Working with family can be difficult, but successful sibling agricultural operations seem to leverage the unique advantages of their relationships to create growth for their farms.

Investment fund purchases

The leading competitors for land in rural Canada are investment funds. Some like One Earth Farms are actually ventures seeking to profit by farming the land they purchase or lease. However, most funds are more interested in owning land than in farming it.

After purchase, they will rent out the land to a third party, usually on a cash basis, and they are not solely relying on returns from farm operations.

A number of funds openly describe their fund exit strategy as liquidation of the land holdings held in the funds in as little as five years in order to capture increases in the land value for investors.

Some funds focus on finding farmers willing to sell their land to the fund, and then rent the land back to the same farmer. Theoretically, the cash infusion from the land sale enables such farmers to expand their equipment line and therefore increases the amount of land they are able to farm. The question is whether there is additional land in the area to rent and if over the long term the farmer can do as well by renting as by continuing to own land.

Even more troubling is that at least one Canadian agricultural investment fund is RRSP and TFSA eligible. Investors can invest tax-free dollars (in the case of an RRSP) and/or receive tax-free returns from farming and land appreciation (in the case of a TFSA).

Yet farmers must use after-tax dollars to buy land, and pay taxes on farm and land returns.

Foreign investment

Farmers’ biggest concern may be foreign purchase and ownership of Canadian farmland. Globally we are witnessing a massive buy-up of farmland by government agencies and investment funds working on their government’s behalf.

In September, the China news agency Star Online reported that China had signed an agreement with KSG Agro for the purchase of 250,000 acres of Ukrainian farmland. The South China Morning Post further reported that this was the first stage of a 50-year plan that would see China owning 7.5 million acres of farmland in Ukraine, roughly 10 per cent of the farmland in the region.

Unfortunately, there is very little tracking of the transnational purchase of farmland. Landmatrix.org is an independent global initiative that relies on crowdsourcing to identify deals because land deals are inherently non-transparent. (Because it focuses on land purchases made in low- and middle-income countries, foreign land purchases in Canada aren’t usually in the Landmatrix data set.)

China isn’t the only country seeking farmland abroad. Other Asian nations including South Korea and India that have large populations and too little land to meet their food needs domestically are actively seeking to purchase land overseas. Rich Middle Eastern nations are also trading oil dollars for land globally. Landmatrix.org currently lists information from 851 international land deals totalling some 75 million acres.

Even if we could track all transnational land transactions, it would be difficult for Canada to be critical of such deals because Canadians and Canadian companies have purchased farmland around the globe.

In 2011, the Alberta Investment Management Corporation (AIMCo), a Crown corporation which invests on behalf of numerous Alberta pension, endowment and government funds, purchased 2,500 square km (about 960,000 acres) of Australia timber and agriculture land.

Sprott Resources, best known in the Canadian agricultural community as the ownership behind One Earth Farms, has also invested $28.7 million to buy seven per cent ownership of the Union Agriculture Group, which in terms of landholdings is the largest agricultural business in Uruguay, farming more than a quarter-million acres.

Brookfield Asset Management is a publicly traded Canadian company that manages over $175 billion of assets on behalf of its clients. Brookfield has invested over $5 billion of that amount in agricultural and timber assets, primarily in Brazil.

Permanent losses

Permanent loss of farmland is possibly the greatest fear for farmers. Urban encroachment continues to take some of the most productive lands out of agriculture. StatsCan data show the amount of farmland in Canada plunged by five million acres between 2006 and 2011.

While this loss of farmland is centred primarily around major urban centres, it affects the price of all farmland as the farmers flush with cash from their sale to land developers compete with farmers in other areas to purchase replacement land.

But even rural areas are attracting developers interested in transforming farmland into acreages and recreational areas.

The phenomenon has become so severe in the crowded northeastern U.S. that even the conservation land trusts established to prevent the loss of agriculture land are failing. Fully one-quarter of the land trusts that oversee these conservation easements are now said to have collapsed because non-farmers bought the land.

According to Lindsay Lusher Shute, a founder of the National Young Farmers Coalition who farms in upstate New York, the problem is so big that the state of Vermont has jumped in forcefully.

That state now requires prospective purchasers of protected farmland to derive at least half of their income from farming, or have a business plan that demonstrates an ability to run a viable farm business.

If Vermont’s state trust doesn’t think the purchaser has the farm creds to keep the land in agriculture, it can step in and find its own buyer, pricing the land according to its agricultural value.

Shute feels farmland must be kept for farmers, and she believes it is important something be done now because, she calculates, “In the next 20 years, 70 per cent of the nation’s farmland will change hands.”

What farmers need to do

In 2002, Compas Inc. polled Canadian CEOs and business leaders for their opinions of foreign ownership restrictions in Canada. Those polled favoured loosening restrictions of foreign ownership in most industries. According to the Compas report: “The one notable exception is farmland, where as many business leaders favour a tightening as a loosening of restrictions.”

Nothing defines a country more than the land it controls. Nothing is more important to a government than ensuring that the food needs of its citizens are met. Yet there are few restrictions on ownership and use of farmland in Canada, and the restrictions that are in place can be easily appealed by any buyer. Worse yet, it appears for the most part, government and the public in general do not know and don’t care who is purchasing our farmland, even though the future of our country and food supply depend on it.

Farmland ownership is a very complex issue and we need a national discussion immediately to decide if farmland is an asset that should be protected for farmers and agricultural production or if farmland is simply a commodity to be traded to the highest bidder.

We need to decide who should grow our food in the future, and who will own and control the land where that food is produced. Regardless of the answers, we need a much better system of tracking farmland sales, both domestically and internationally, to ensure farmland owners are dedicated to agricultural production.