It’s the forces of capitalism.” CEO Claude Lafleur outlines his strategy for La Coop fédérée. “You get bigger or you disappear.”

It means the co-op— the largest in Quebec with 95 retail outlets, plus active involvement in meat processing

and petroleum — is looking far beyond Quebec’s borders.

In fact, executives at the co-op had already been scouting for expansion opportunities for a while last October when they reeled in Agronomy Company of Canada (ACC), their new catch that includes grain and fertilizer terminals in Belton, Ont., and part ownership in 20 Agromart crop input retailers in the province.

Read Also

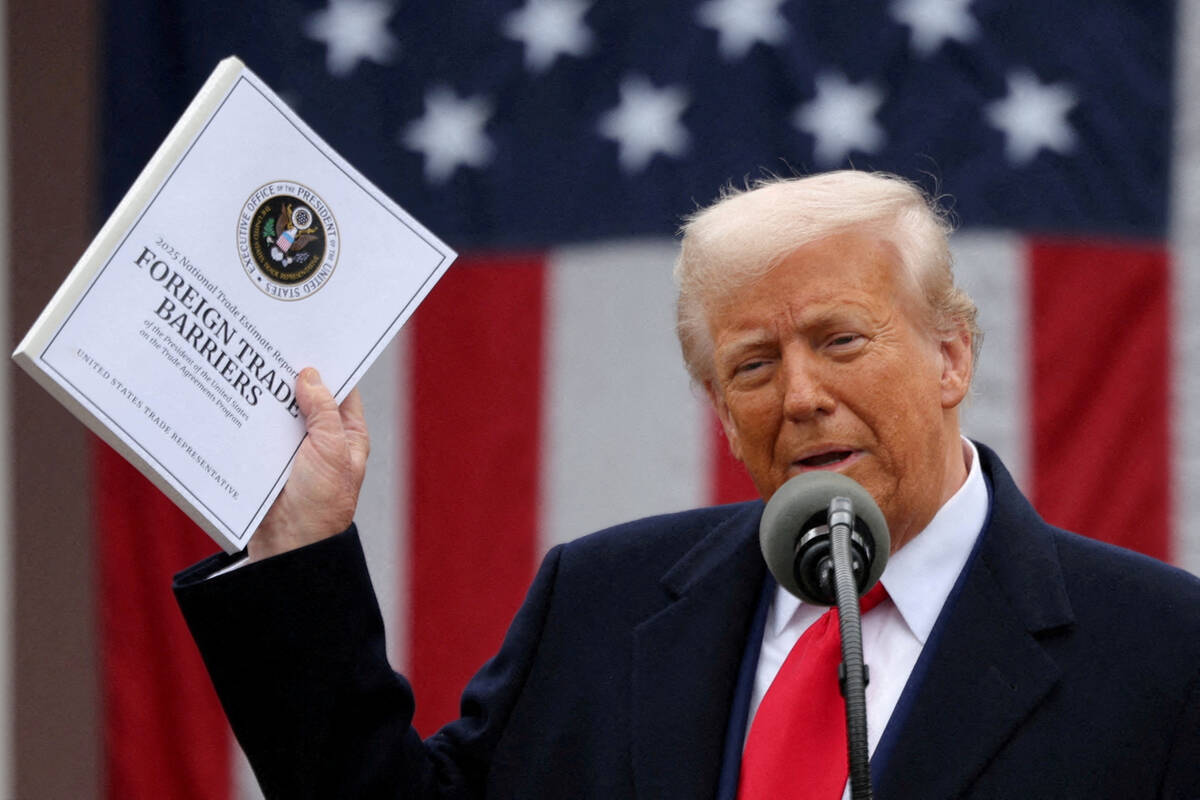

Producers aren’t panicking over tariffs and trade threats

The Manitoba Canola Growers Association (MCGA) surveyed its members this spring to get a sense of how trade uncertainty was…

It’s a move that doubles the co-op’s buying power, propelling the company to the top of Eastern Canada’s crop input retailer list.

It’s also a move that continues to reverberate, Lafleur says. Fertilizer companies are already knocking on the new giant’s door with interesting business deals, and crop protection companies are eyeing plans to get preferred status with the new must-have retailer.

It’s just business, Lafleur told Country Guide. Being a cooperative doesn’t put you in a different ball game. “Competitors are getting bigger and more aggressive. It’s a tough game.”

For Lafleur, the goal is to survive and to continue to provide co-op members with products and services at competitive prices. In that context, synergies and volume savings from the purchase of the Agronomy group may never actually show up on members’ crop input bill, Lafleur says. But members will still have their co-op.

Few people across Canada will disagree with his “get big or die” logic, especially in a world where fertilizer and crop protection markets are dominated by a handful of multinationals. But when the laws of capitalism result in Quebec buying Ontario, are we to fear a cultural invasion?

La Coop fédérée isn’t interested in planting its flag all over Ontario, Lafleur said. Agromarts will keep operating in English, with the same logo. “These people have been around for a long time and they are very efficient. We are very impressed.”

Agromarts operate in a similar way to Quebec’s Agrocentres, a six-location crop input retailer network with 50-50 ownership between La Coop fédérée and local owners.

One main difference is that Ontario’s 16 Agromarts serve farmers that enjoy much less income protection than Quebec’s. This makes high efficiency a prime concern, both for farmer and retailers, Lafleur explains.

Learning, though, will be a two-way street. “We’ll copy a part of what Agromarts do,” Lafleur says, pointing to its business practices and services such as crop spraying.

Belton employees and Agromart dealers had real concerns about Agronomy slipping into Quebec hands, Lafleur admits. Like anglos across Canada, he says, Ontarians are sensitive to language issues and they take a lot of pride in the way they do business.

“Are we better off with Americans or with French-Canadians? That’s the question they have to ask themselves,” Lafleur said. “At La Coop fédérée, we are determined to prove that the partnership will be better with us, because they will also learn from us.”

The Agronomy acquisition is expected to add stability to La Coop fédérée’s activities. Its pork processing and marketing (Olymel brand) division has had more downs than ups in recent years. Its farmer co-operatives, including the one in St-Isidore, in Eastern Ontario, have been steadily gaining market share, but as farmer numbers dwindle, major restructuring has become necessary to eliminate feed mills operating at a fraction of their capacity.

Significant synergy is also expected from the Agronony deal. For example, a 35,000-tonne boatload of fertilizer could be unloaded at two locations in Quebec and one in Ontario. With that added capacity, La Coop fédérée buyers can easily order in a boat when a good deal comes up.

“We are doubling our supply volumes,” La Coop fédérée