There’s less and less doubt about it. What we’re currently facing is a global recession in commodities of all types.

Right now the world has plenty of potash, copper, oil, gold and grain. Producers of all types have responded to the extremely strong price signals they’ve been receiving lately and have grown their productivity.

That’s meant new energy projects producing technology via fracking and renewables, new mines coughing up more metals and minerals, and new plants churning out chemicals.

In the global grain market, it’s meant productivity investments, especially in longtime basket cases like the Black Sea area of the former Soviet Union, plus new acres primarily in underutilized areas such as parts of Brazil.

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

Those investments have met the explosion in grain demand, which came primarily from two sources, biofuel mandates and the growing demand from rapidly modernizing countries like China. Now that this demand growth appears to be waning, however, we’re back in an oversupply situation in most global grains, and that’s weighing on prices.

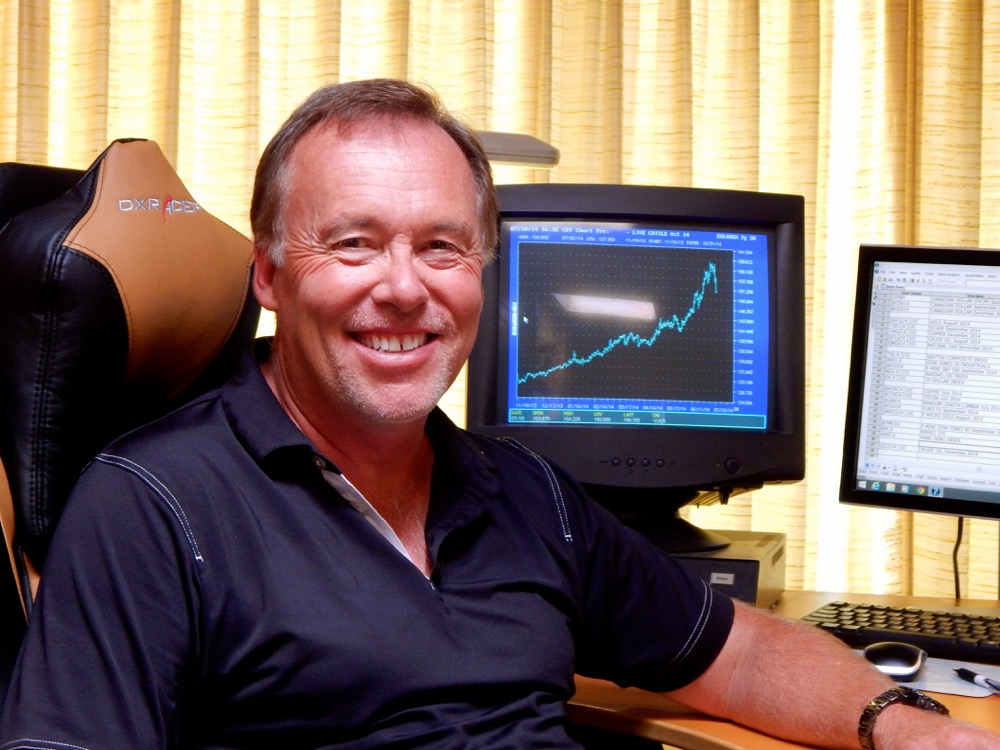

Canadian producers have been somewhat shielded from this effect as the Canadian dollar has fallen along with commodity prices — but even so, it’s back to scratching for break-even for these growers, says grain market analyst Errol Anderson from his office in Calgary.

“We’re enduring the depths of this commodity crisis right now, there’s no doubt about it,” Anderson told Country Guide during a recent conversation. “It’s a recession in global commodities, and the question is, what will it take to jar them out of it?”

For at least the next two to three years, Anderson doesn’t see catalyst in growing demand. All signs point to a slowing global economy, with the key item to watch being the ocean-going container freight index. That’s a global transportation index reflecting the cost of shipping across the seas, and while it might seem a bit arcane, it’s definitely a leading indicator to watch for economic recovery or evidence of a slowdown, Anderson says.

“Containerized ocean freight rates are basically a signal on the health of the global economy,” Anderson says. “It represents the true demand of goods around the world. As an example, the Shanghai containerized freight index reflecting ocean freight between China and Europe is now 45 per cent below levels seen even during the 2009 financial crisis”

That’s not great news for anyone selling grain, or any commodity for that matter. It suggests a slowdown in global demand especially from emerging and commodity-based economies. Until this demand for raw commodities improves, excess productive capacity in economies like China will remain under-utilized. It will take a while, maybe years for this demand to improve.

Farmers might be tempted to just throw their hands in the air and accept it’s back to the bad old days — but Anderson insists that now, more than ever, farmers need to look at things just a bit differently. Every crisis is also an opportunity, the old wags say, and opportunity just might be knocking again — but it takes the right attitude and marketing skills to find business profitability in an otherwise bearish marketplace.

“When times get tough, farmers tend to complain they’re just price-takers, and they have no control over what they’re paid. To an extent that’s true — but to an extent it’s also true of every other business out there,” Anderson says. “A down economy impacts every business regardless of industry. Successful businesses are the ones that come up with a strategy to lock on profits. And a farmer who wants to thrive under these more challenging market conditions needs a plan.”

Country Guide: With all that’s going on these days, how do you know your marketing plan is solid?

Errol Anderson: In a lot of ways, that’s going to come down to how a farmer is feeling about their marketing plan as the year rolls on.

If you find yourself constantly complaining about cash prices, that’s a pretty good sign that what you’re doing isn’t working.

In a way, the world is a big swimming pool and a marketing plan is learning how to swim in it. Once you’ve learned to swim, you just get on with the business of swimming, rather than complain the water is too deep or too cold. Complaining about prices is a sign of marketing weakness, not strength.

That’s not to say there won’t be challenges. Life hands us all challenges, farmers and non-farmers alike. What doesn’t work for any of us, however, is an ongoing sense of victimhood. If what you’re doing isn’t working, be prepared to change it, because as they say, doing the same thing over and over again expecting a different result can be the definition of business madness.

Building a plan isn’t an easy thing. It also isn’t a one-size-fits-all project. This is really building a custom car that you feel comfortable in operating. No two custom cars are alike, but each is the perfect car for its owner because it’s built exactly to his or her specifications.

Once you’re done building your plan, it should make you feel comfortable that it meets the needs of your farm business. And once that plan is in place, revisit it regularly. Make sure the goals for this year still make sense. Regular business meetings with everyone who has a financial interest are a perfect time to review and fine tune your marketing plans. It is an evolving process.

CG: In your experience, which marketing tools work best for growers?

EA: The key is flexibility and diversification. There are a lot of pricing tools out there that offer control and market flexibility. Tied to a marketing plan, these tools can zero in and produce a steady flow of profitable pricing. This avoids that sinking feeling that growers are simply price-takers. Growers can take control of their own pricing destiny.

For instance, growers who need cash flow or who need bin space have alternatives to lessen their price risk, meaning they can take advantage of a price rise after the grain has left the bin. They may have to sell grain today, but there are tools available to take advantage of a price rise later in the crop year should it occur.

But there are also tools to lock futures or basis levels that may or may not commit to delivery. Sometimes you will want to commit to delivery to ensure physical grain movement. Sometimes it is best not to commit to delivery due to production uncertainty. I feel strongly that a solid marketing plan is a blend between cash contracts and a commodity trading account. They both have their advantages and disadvantages at times.

So you need to understand the cash market tools at your disposal from local buyers and how a commodity trading account can strengthen your business management. Should you find a broker you’re comfortable with, set up an account so you’re ready to use it if the situation warrants it.

Some growers use a trading account depending on basis levels or to avoid making cash grain delivery commitments. If basis levels are attractive, cash contracts stand out. But if basis levels are weak, commodity accounts have a role to manage this.

Remember, options don’t commit the grower to physical delivery and there is no risk of margin calls. That can be a bonus at times. But you can’t make physical grain delivery. Be cautious of trading futures outright. Market volatility is not for the faint of heart. Trading futures outright takes discipline to tie it to a plan.

CG: Many producers may be relatively happy about crop they have already priced, but they’re concerned about unpriced grain. Any tips?

EA: That’s nothing unusual, though yes, that feeling might be a bit stark this year. But there’s always a point in the crop year where your attention turns to how to market the crop remaining in storage. Two key factors impacting this decision are cash flow and bin space, and toward the end of the crop year the decision may be, do I sell it this year or next?

Here’s where market management and understanding strategies can be helpful for taking control. I’m of the view, that you should move the grain off the farm as quickly as possible and try to move your grain in the same crop year you produce it. Long-term farm storage sometimes pays off, but not often.

Most often, you are not paid for the risk of storing grain on farm, to say nothing of the storage issues.

Let me use a canola example. Imagine you sell your canola for $10.75 a bushel, which is a reasonable cash price. But you think there’s some potential for El Niño-related market activity and you don’t want to miss that potential upside. So you purchase a call option — let’s say the call premium costs you 25 cents a bushel — that gives you the right to buy that amount of canola at a specified strike price into the future.

If prices stay where they are or go down, the call premiums will eventually expire worthless and you’re out the 25-cent-a-bushel premium you’ve paid. But if prices go up, your call option premium increases in value. You can add these gains to the $10.75 a bushel you’ve already got in your pocket. But if canola prices drop to say $9/bu., your call option will expire worthless and you would still net $10.50/bu. on your canola ($10.75/bu. cash sale — 25-cent/bu. loss on the call).

On the cash market side, this is where you can really benefit from knowing your local market. What does a good basis look like? Have you shopped your samples around? Make sure you have a bond with your buyers. If there’s a sudden need for product, premiums may appear, and you’ll be on the list to get that call. Farmers need to be salesmen too. You really need to work your local buyers and understand what marketing tools they can provide for your operation.

CG: If we’re likely looking at a prolonged period of softer prices, is it also time to eye new-crop prices? Should grain be priced well ahead of the combine to lock in profits?

EA: I’m a fan of forward selling crop, within reason. You should be prepared to sell before you go to the field, by as much as 30 per cent of your expected production if a winter rally occurs, then up to half your expected production may be profitably priced before combines hit the field. Then you know your fall cash flow needs are covered by profitably priced grain.

Once you have completed harvest, let’s say you have about 50 per cent of your grain unpriced while you are already starting to look forward to pricing new crop. It’s like turning your marketing decisions about 180 degrees forward. With this thought, a grower may be looking to price both old- and new-crop grain on rallies. Again, knowing your production costs and bill payment schedules will lend a hand in these decisions. Farmers who are prepared and can move quickly when opportunities present themselves are often most successful.

CG: Obviously there are going to be things happening that farmers have no influence over — what are the key global issues to watch over the next while?

EA: There’s no doubt there are a number of factors farmers just don’t have control over right now. For example, we don’t really know how the U.S. Federal Reserve policy on interest rates will play out. If it supports further gains in the U.S. dollar, that could further slow exports, including grain. This would impact U.S. prices which will also impact ours. It could trigger further price pressure, at least temporarily. A weaker Canadian dollar should at least partially offset that, but U.S. markets tend to dictate Canadian price direction.

Also, China’s economic slowdown has a direct impact on all global commodity prices. This will affect the volume of trade and prices between Canada and China in the months and years ahead. The global currency war which has been generated by central banks’ focus on money printing also has a huge impact on prices, and is also beyond our control. Brazilian farmers are now making more money growing soybeans than ever before because of the collapse of the real currency. This will continue to push South American soybean plantings. And Russia has gained global wheat market share due to the collapse of its ruble.

It has been a race to the bottom for currencies as every country wants to gain export competitive advantage.

Despite these global issues, however, there will be attractive pricing opportunities. Growers need to be responsive to them. The global commodity downturn impacts everyone, and it definitely heightens the need and value for a disciplined marketing plan that will lock in those profits.

This article first appeared as “Busted flat” in the January 2015 issue of Country Guide