On Aug. 10, 2020, Brad Crammond noticed some sudden and premature die-off in a seemingly healthy field of canola. “We’ve had issues with blackleg in the past,” says the farmer from Austin, Man., “and I could tell this was something different.”

So he called Canola Council of Canada agronomy specialist Angela Brackenreed to take a look. “The symptoms were advanced verticillium stripe,” Brackenreed says. “It was pretty obvious.” Samples sent to Manitoba’s PSI Lab confirmed the diagnosis.

The disease, caused by the Verticillium longisporum pathogen, is relatively new to canola in Canada. It was first detected in Manitoba in 2014. In 2015, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) surveyors found the pathogen in six provinces, including all three Prairie provinces. By 2020, the incidence rate in some fields was high enough to cause yield loss. For the Manitoba 2021 disease survey, the first year that surveyors had an effective system to include verticillium stripe, 30 per cent of fields had the disease. In those fields 15 per cent of plants, on average, showed symptoms.

Read Also

How scientists are using DNA and climate data to breed crops of the future

A method for forecasting how crops will perform in different environments so that plant breeders can quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

Verticillium stripe, unlike other diseases, can be more severe in dry conditions, which could explain why the disease reached new heights in 2021. Crammond, experienced with the symptoms, saw verticillium stripe last season as well.

“Now that we know what we’re looking for, we’re finding it all across the Prairies,” Brackenreed says.

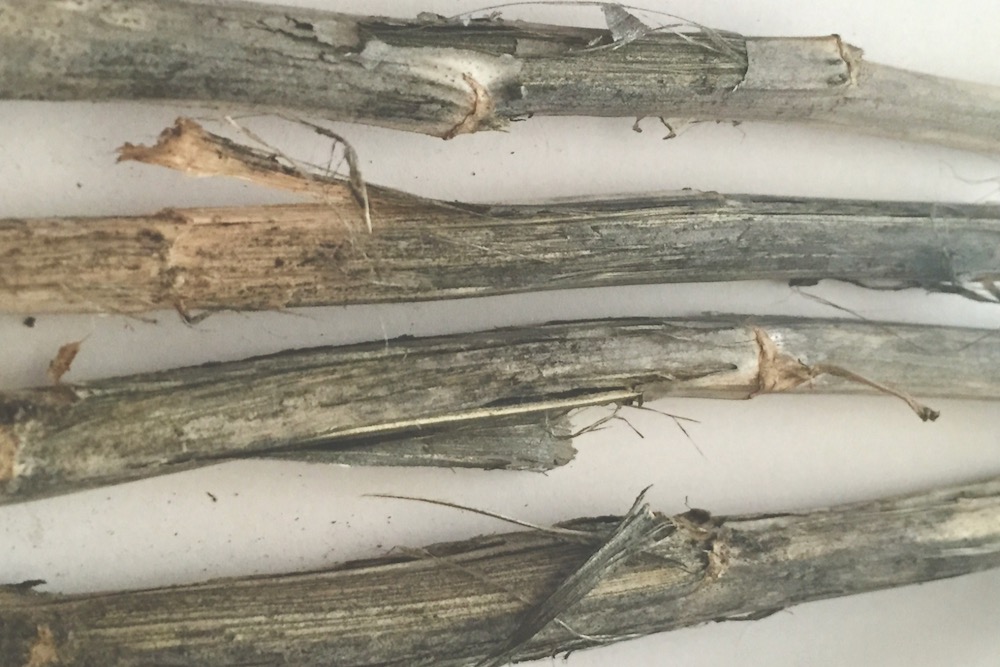

Early infection can show up as grey or tan diseased stripes up one half of the stem — hence the “stripe” name. Likewise, infected leaves can be dying on one side and healthy on the other.

As verticillium infection progresses, the epidermis will peel away from weakened stems to reveal tiny specks called microsclerotia underneath. These specks may seem similar to blackleg pycnidia, but verticillium specks are much smaller. Verticillium stripe, like blackleg, also causes a darkening of the stem cross-section. While blackleg causes distinct black wedge shapes, verticillium discolouration is diffuse throughout the cross-section and gets continually darker as microsclerotia build up. Verticillium infection can extend up the stem, while blackleg is concentrated in the crown around ground level. Eventually, verticillium infection blocks the transfer of water and nutrients, weakening the stem and killing the plant.

“Because we’re letting canola stand longer, either for straight combining or later swathing, we may be noticing the disease more than we used to,” Brackenreed says. “Verticillium infection can also continue to advance after canola plants are swathed, but people don’t usually look at windrows that closely.”

In 2020, Crammond had stems breaking off and toppling over, making it look from a distance like a case of severe lodging. “We had some big winds in August that year and a lot of talk on Twitter was about crops going down and making harvest difficult,” he says. “In retrospect, the cause for many of these cases may have been verticillium stripe.”

Cultivar differences

Crammond knows the disease cut yields on his farm, but Canada doesn’t yet have a system to estimate the amount of loss.

In Europe, which also has a problem with verticillium stripe in oilseed rape (Brassica napus), a 2008 study by Dunker et al. estimated yield loss at 10 to 50 per cent. In 2016, Jasper Depotter, a plant pathology researcher at the University of Cologne, published results from field trials in the United Kingdom. Depotter’s study showed yield loss as high as 34 per cent, with differences among cultivars. Based on this, he says, “in a bad year on a susceptible cultivar, the estimates of Dunker seem realistic.”

Genetic differences are showing up in Canadian research as well. Dilantha Fernando, professor in the department of plant science at the University of Manitoba, tested germplasm from international sources and dozens of lines supplied by Canadian seed companies. He says some have clearly superior levels of resistance, but lines supplied to him were not identified so he doesn’t know if any were commercial cultivars.

In Saskatoon, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist Hossein Borhan is screening 50 Brassica napus lines within the AAFC nested association mapping (NAM) program to compare their verticillium stripe resistance. Some lines are very resistant, some are very susceptible, he says.

Crammond’s on-farm experience shows differences between cultivars. In 2021, he ran out of seed in one field and finished the final eight acres with a different cultivar. While most of the field was at risk of shelling out due to high levels of verticillium stripe, the eight acres of a different variety had “no issues,” he says.

Rotation helps

No fungicide solution is available at this time. Genetic resistance will likely provide the greatest level of protection, with effective support from crop rotation.

While researchers do not know how many years between canola crops are required to provide an effective reduction in risk, Crammond’s experience shows that rotation can work. One of his canola fields in 2020 was on a half section with a mixed cropping history. Eighty acres in the middle had quinoa, soybeans and wheat over the previous five years — no canola. The rest had been in a wheat- canola rotation for “quite some time,” he says. While the rest of the field turned brown prematurely due to verticillium stripe, the 80 acres with a longer break between canola crops stayed green and healthy. It was all the same cultivar.

“The increased instances of verticillium stripe make crop rotation even more important, in my opinion,” Crammond says.

“Rotation has so many other benefits, so it’s worth a shot,” Brackenreed says. Some evidence suggests that incorporating stubble through tillage can also increase the longevity of the spores, she adds, so minimum tillage may provide additional help.

Brackenreed recommends canola growers all across the Prairies keep an eye out for verticillium stripe in 2022. “Learn to identify the disease so you know what you’re dealing with,” she says. “And because there seems to be a genetic component, make sure to compare results from different cultivars. While we don’t know at this time what cultivars have enhanced resistance, genetic diversity from using different cultivars could buffer the risk.”

-Jay Whetter is a communications manager with the Canola Council of Canada.