Dan Needles is the author of “Wingfield Farm” stage plays. His column is a monthly feature in Country Guide

Last month, our Township Council launched Phase 4 of their Going Green garbage plan, adding yet another plastic bin that we’re supposed to use for organic wastes. Apparently this is happening all across the country. We now have blue, grey and green plastic bins, a one-bag limit and four Toxic Tuesdays a year for dropping off paint cans and household cleaners to a number of transfer stations dotted around the township. To top it off, they mailed us a 10-pound recycling manual last week that reads like the fine print on a travel insurance policy. I have been studying it ever since, pausing only for sleep and prayer.

Read Also

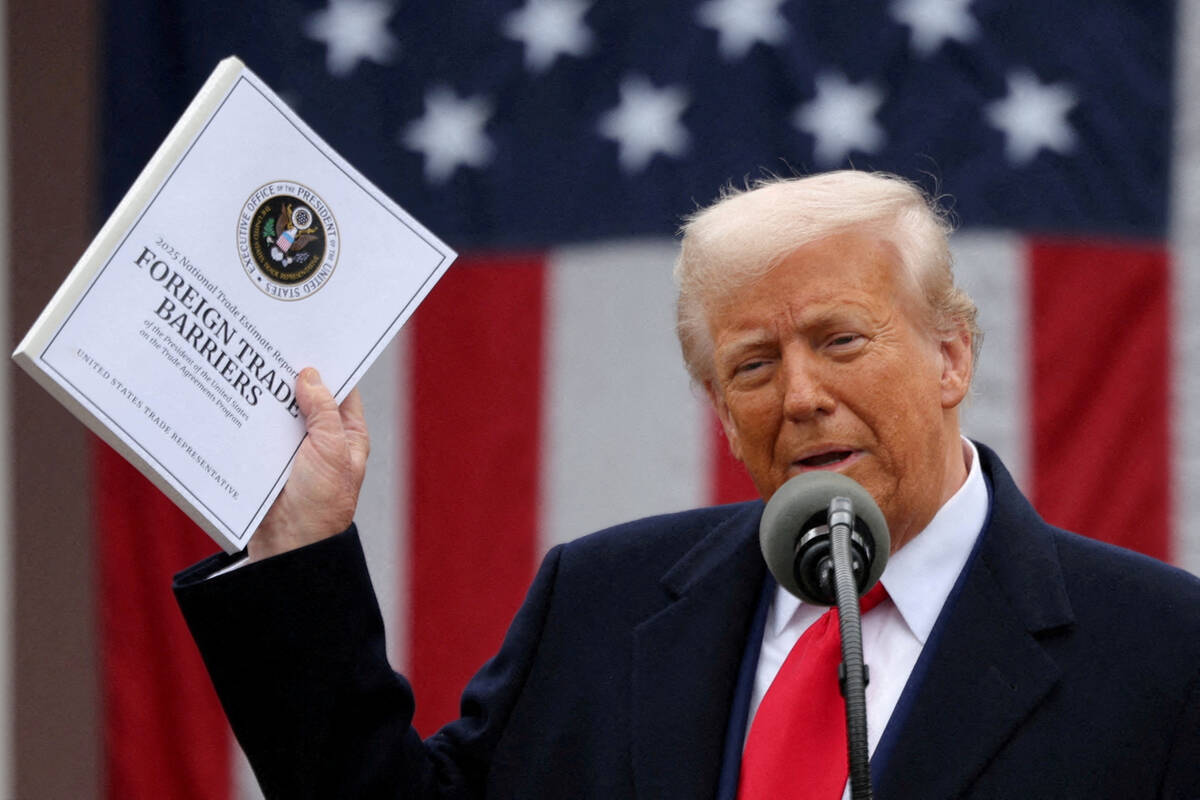

Producers aren’t panicking over tariffs and trade threats

The Manitoba Canola Growers Association (MCGA) surveyed its members this spring to get a sense of how trade uncertainty was…

You have to remember that it’s only about 10 years since the township decided to give us municipal garbage pickup out here in Petunia Valley. That turned out to be Phase One. The trick then was to get the farmers to give up habits they have cultivated since pioneer days, and drag their trash to the road. That campaign was very successful, but it seems the Township had almost immediate reason to regret their decision and they have been backtracking ever since. They imposed a three-bag limit fairly quickly, then a two-bag limit with a blue box for recyclables. When no one would pay the $15 fee for the blue bins they gave them away free. Last year, they distributed a grey bin for plastic recycling, squeezed us down to a one-bag limit and hired a garbage policeman. If the latest campaign fails to reduce the volume of waste going to landfill, the only measure left to them will be to install a tail-gunner on the garbage trucks.

The new garbage policeman is Lefty O’Leary, a man who has spent most of his adult life in waste recovery. Lefty lost his right arm in a farm accident about 30 years ago and they gave him a job at the township landfill, helping residents haul stuff off the back of their pickups with the benefit of his steel hook. I once asked my neighbour Vern Bunton how Lefty lost his arm.

“I don’t know,” said Vern. “But it made him about 50 per cent more honest.”

Lefty made a good living between the tips people gave him and the reclamation shop he ran out of the dump gate. But then the County stepped in and took over the landfill site, erecting enormous berms and a multi-million dollar drainage system for leachate. They closed Lefty’s shop and put up a big sign that read “No Scavenging.” In Persephone Township, that’s like telling us not to breathe.

Lefty just shrugged his shoulders and talked the County into letting him handle the leaf and yard waste in a separate part of the dump. After three seasons he was able to build a big house on Hall’s Hill with the proceeds from his composting business. The only way the County could break his 10-year contract was to appoint him Municipal Waste Control Officer at $80,000 a year.

Lefty patrols the sideroad every Thursday looking for overweight bags and dead racoons in the green bins, and serving citations to all offenders. Tempers are rising and Vern says Lefty will be lucky to finish out his career with his one good arm.

If the County had asked me, I would have told them they already have a garbage police force in place. It is unpaid, eternally vigilant and overwhelmingly effective. I am speaking, of course, about our children, who have been drilled in recycling every day of their lives since kindergarten at the Hall’s Hill Public School. They may not be able to spell or count past their own fingers but they have a university level understanding of environmental issues.

We all live in fear of my 11-year-old daughter, Fruit Loop, because she is sitting at the heavy end of the environmental teeter-totter. All the science is on her side and we will just have to change our habits.

But I do envy Owly Drysdale, the old cattleman up on Hall’s Hill. He is childless and lives at the end of a rocky lane that lies beyond the reach of everything but a police helicopter. He still lobs his jam jars into a heap 30 feet from his back door and tends the eternal flame in his oil drum by the woodpile, as he has done since 1926.

Fruit Loop has her eye on him. I think they are pretty evenly matched.